Purchase tickets for one of our guided tours.

Journey to the past

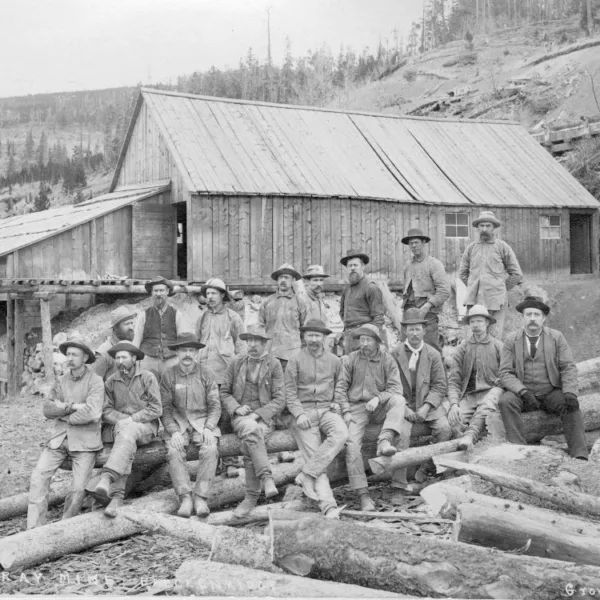

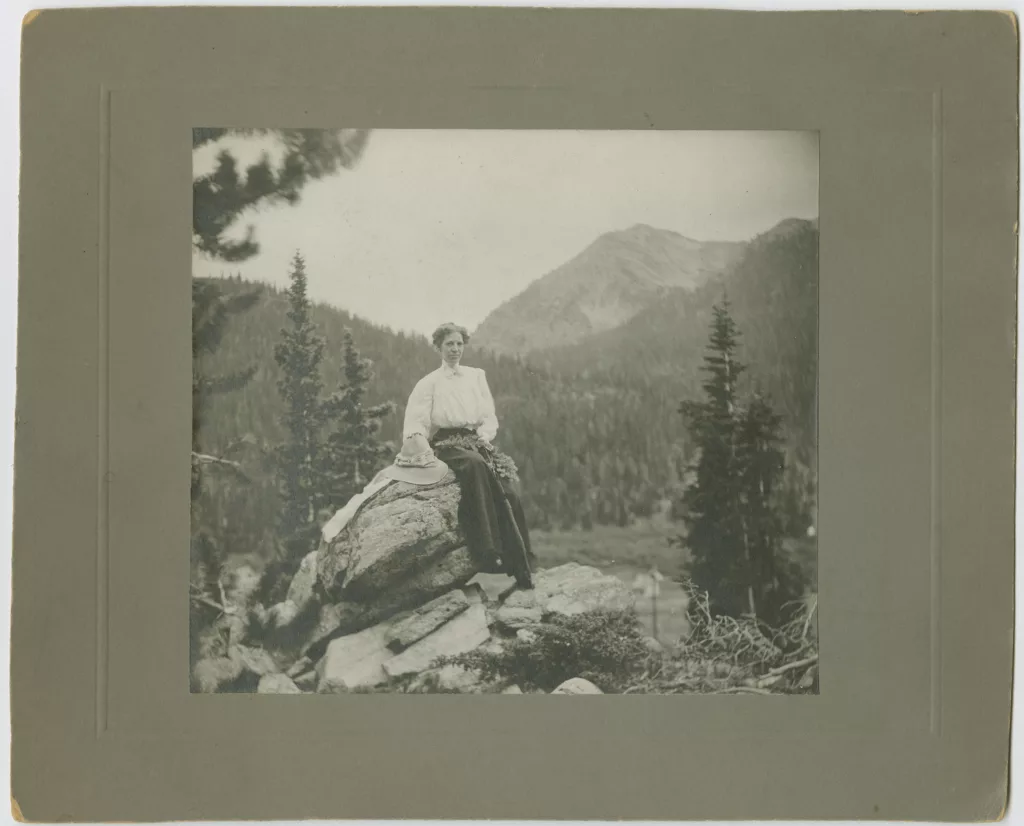

Visit the Breckenridge History Archives digital collections to view and download images from the town’s history

High Line Railroad on MTN TV

You have a great mission – inspiring! History is such a gift; thank you for opening it to us.

Leigh did an amazing job. She was so knowledgeable, interesting and kind. Plus, we loved snowshoeing in such a beautiful location while learning at the history of mining.

Overall the selection, payment, and the hike were flawless. Mariana is an outstanding guide and was so informative. We really enjoyed our morning snowshoe hike. Thank you!

Everything was really, really good. Though I always believe there is room to improve, I couldn’t say how the experience could have been improved. It was fantastic, both guides were great, we learned a lot and found some gold. I would recommend this to anyone one of any age. Fun, educational time.

Very well organized, from the booking through the hike. Our guide was 100% outstanding. Preston was very knowledgeable about the history and details of what we saw, and if he didn’t have an answer (which was rare), he told us that. Could not have been better.

Wonderful historian and captivating story teller. Was hanging on every word. Fabulous!

Our guide, Leigh, was fabulous. Even with the rain, she kept smiling and sharing great stories about Breckenridge.

June was amazing, as was the other gentleman! June took her time to explain the history of gold mining and helped my two boys immensely in finding flakes of gold in their pans!! Our boys (age 6 and 9) said they had so much fun. The adults learned a lot and had a great time too!! We highly recommend!!

Our guide June, was exceptional! She gave a great history lesson and did a wonderful job demonstrating gold panning. She was also great with the kids.

Sharon was extremely knowledgeable, professional and communicated everything in an interesting manner. We left the tour feeling as if we made a friend.

Ronnie was such a great tour guide. Very engaging and knowledgeable!

Our tour guide June was wonderful, we had a great experience, highly recommend.

We have done historic tours in other cities we travel to, and this nonprofit is by far the most professional. Every tour guide here answered our questions well in addition to providing great context.

Our guide, Sharon, did a tour that was very informational and interesting. She also had many humorous antidotes about the history of Breckenridge which made the tour fun! We will definitely recommend this tour to friends.

Sharon was amazing and very informative. Took time to find out more about us and what we wanted to see and do. Full of fun facts.

Our guide was knowledgeable, courteous, thoughtful, and fun to listen to! She was skilled at leading and managing a group, and patient and engaging with those of all ages.