Breckenridge, CO: Primer Festival Ullr Dag

13 de febrero de 2021 | Category: Nuestra historia colectiva

El primer carnaval de invierno de Breckenridge, Ullr Dag, tenía una tarea difícil: hacer que Breckenridge destacara. Breckenridge era una de las muchas nuevas estaciones de esquí de Colorado a principios de los años sesenta, y la primera temporada no tuvo mucho éxito.

De hecho, fue tal el fracaso que los propietarios cambiaron el nombre de la estación de esquí y empezaron de nuevo para la temporada 1962-63. Se convocó una celebración. Había que celebrarlo. Pero, ¿cómo diferenciar el carnaval de invierno de Breckenridge del montón de carnavales tradicionales de todo el estado?

Los noruegos y un grupo de jóvenes entusiastas unieron sus sueños a la incipiente ciudad de esquí de Breckenridge. Ideas locas, extravagantes y salvajes hicieron que los festivales Ullr Dag fueran inolvidables.

Los noruegos Trygve Berge y Sigurd Rockne llegaron a Breckenridge para fundar la escuela de esquí y trajeron consigo la mitología nórdica. Ullr, el dios nórdico del invierno y patrón de los esquiadores, inspiró el tema. La histórica Celebración de la Tierra de Nadie de Breckenridge sirvió de telón de fondo para establecer Breckenridge como Reino. Las ideas fluyeron a partir de ahí. Un Reino necesitaba un rey y una reina, su propia moneda y visados para entrar. Las actividades tradicionales del carnaval de invierno, como un desfile, una procesión de antorchas y un baile, aportaron la suficiente familiaridad como para que el acontecimiento tuviera visos de realidad. Comenzaba el Ullr Dag (Día de Ull).

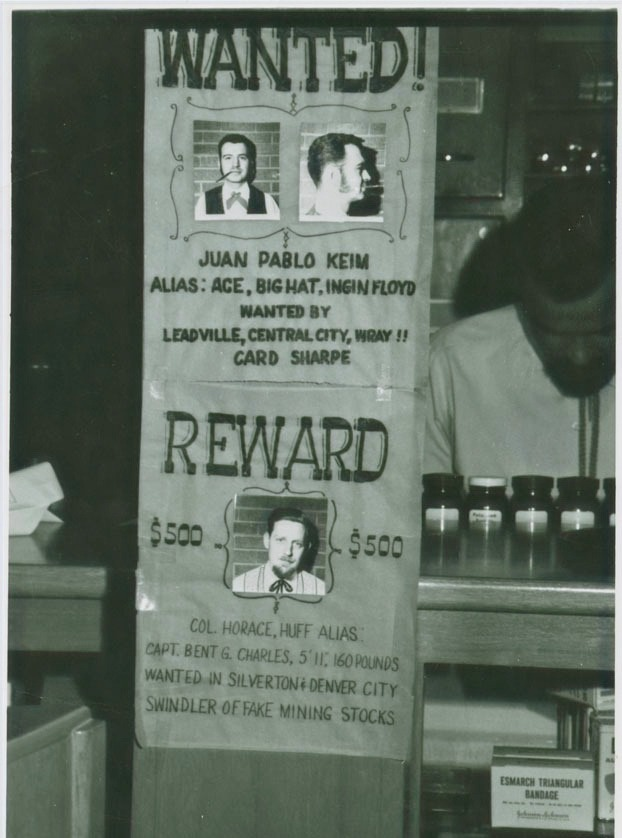

El primer objetivo: llamar la atención. Brillantes vendedores irrumpieron en una reunión del Consejo Municipal para exigir el retorno al Reino, preparando el terreno para el acontecimiento. Hombres robustos esquiaron desde Breckenridge hasta Denver para invitar al gobernador a ser el primer Rey de Breckenridge. Las conversaciones sobre la secesión atrajeron la atención del Fiscal General de Estados Unidos.

Cuando el Departamento del Tesoro de Estados Unidos exigió a los organizadores del evento Ullr Dag que dejaran de acuñar sus propias monedas para ponerlas en circulación durante el evento, la prensa se dio por enterada. Los habitantes de Breckenridge no podían pagar esa notoriedad. "Acuñábamos monedas, lo cual era contrario a la ley", afirma Bob Atchison, director de relaciones públicas de la estación de esquí de Breckenridge en 1963.

Las intrigas entre estaciones de esquí rivales afloraron con la saga de las monedas Ullr. Alguien denunció a Breckenridge ante el Departamento del Tesoro de EE UU. Los souvenirs de monedas, como los talismanes de Ullr, eran habituales en los eventos de Colorado. Robert Theobald, abogado del evento, recordó a los funcionarios del Tesoro que muchos otros lugares emitían estas monedas y "no había habido ningún alboroto". Hacienda admitió que la ley en esta materia rara vez se aplicaba, pero alguien registró una protesta. "Alguna persona está presionando mucho sobre este asunto", citaba el artículo. Theobald señaló: "Alguien intenta crearnos problemas".

Las monedas infractoras fueron barridas y selladas con "no" y "souvenir". Las monedas que escaparon a la alteración son hoy valiosas piezas de coleccionista. Nadie sabe quién presentó la queja ante el Departamento del Tesoro, pero los rumores locales atribuyen la culpa a una estación de esquí cercana, que casualmente planificó su gran fiesta de inauguración el mismo fin de semana que el primer Ullr Dag. De ser cierto, el tiro les salió por la culata. Breckenridge acaparó aún más atención a raíz de la polémica.

Si Breckenridge estaba en apuros, eran buenos apuros. La atención estaba puesta en el primer Ullr Dag. ¿Cómo podría el acontecimiento estar a la altura de la promesa inspirada por las extravagantes presentaciones?

Multitudes de turistas curiosos acudieron al primer Ullr Dag para ver por qué tanto alboroto.

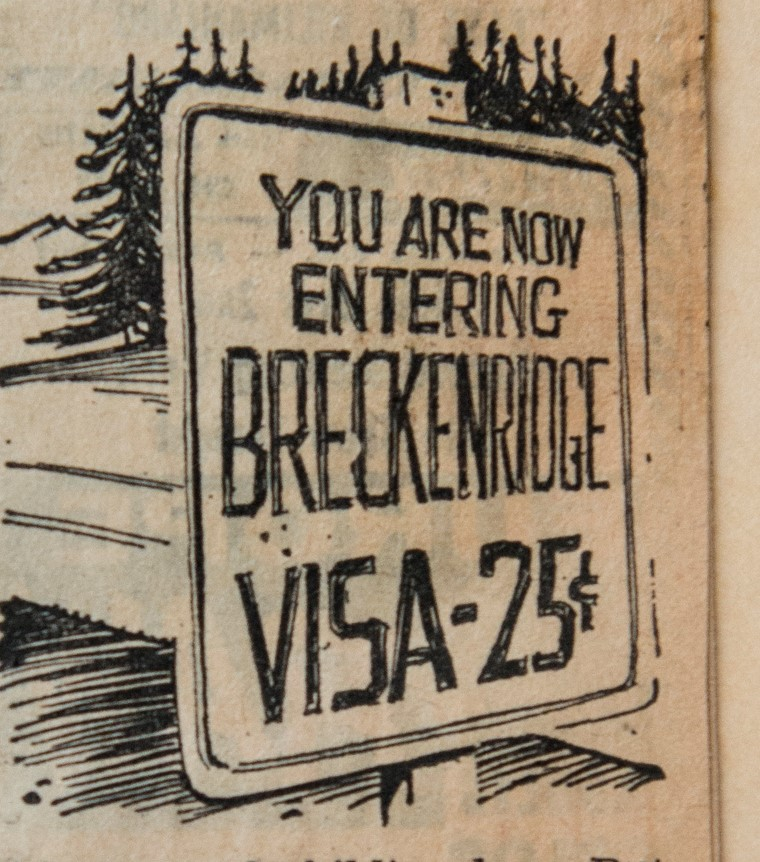

La llegada a Breckenridge requería la compra de un visado por veinticinco céntimos en los dos puntos de entrada: Colorado State Highway 9, también conocida como Main Street norte y sur (Park Avenue no existía en aquella época).

Los payasos Shriner se encargaron de la venta de visados y de la gestión de los vehículos. Siguiendo el famoso estilo Shriner, los coches se colocaron en zig-zag, bloqueando completamente el tráfico. Pero un coche estaba estratégicamente colocado, como una piedra angular, y "si ese único coche pudiera moverse, todo el asunto se desbloquearía", recuerdan Debbie Cope Lee y Sheila Cope Sargent, cuyo padre era uno de los payasos Shriner.

Un turista de Minnesota que se dirigía a Aspen se vio envuelto en el caos. Estaba tan indignado por tener que comprar no sólo un visado al entrar en la ciudad, sino un segundo al salir cuando se dio cuenta del error de su ruta, que escribió una carta de queja al Denver Post. Robert Giles se quejó de que "era una forma extremadamente pobre de publicidad... y reflejaba negativamente el estado en general". Más mala prensa para Breckenridge no aplacó los ánimos, ni alteró Ullr Dag; la exigencia de visado continuó todos los años que existió Ullr Dag.

Si no se adquiría el visado, se visitaba el "hoosegow", una forma laxa de cárcel en uno de los bares locales. Los disfraces eran obligatorios durante todo el evento, y su incumplimiento acarreaba el mismo castigo.

Toda la ciudad se sumó al espíritu de Ullr. Los comercios decoraron sus fachadas. El primer concurso de "esculturas de nieve" ofrecía delicias visuales. Las hermanas Cope recuerdan el barco vikingo construido con nieve a la entrada de la droguería de su padre (ahora Skinny Winter gifts). "Había que atravesar el barco para entrar en la tienda", recuerdan.

El Ullr Dag comenzó la noche del viernes 22 de marzo de 1963 con fuegos artificiales desde la cima del Pico 8, seguidos de un desfile de antorchas por las pistas de esquí. El fuego de Ullr iluminó el centro de la ciudad. La atención se trasladó a Main Street a las 19:45 para el primer desfile del Ullr Dag. Los más veteranos recuerdan que se trataba de un desfile insignificante con unas pocas carrozas. En la oscuridad, probablemente eran difíciles de ver. No es de extrañar que no se conozcan fotos del primer desfile de Ullr Dag.

Las ceremonias de inauguración comenzaron el sábado por la mañana en el Palacio de Justicia de la avenida Lincoln, seguidas de tontas carreras de esquí en la estación de esquí de Breckenridge. Trygve Berge exhibió su famosa voltereta hacia delante sobre esquís en el Bergenhof a la hora del almuerzo. Las actividades en la ciudad incluyeron espectáculos de patinaje sobre hielo y un número de payasos profesionales.

Al caer la noche, el desfile de antorchas repitió su recorrido por las pistas de esquí. Un ajetreado día de diversión y frivolidad concluyó con el Baile Real oficial y la coronación del Gobernador John Love y su esposa Ann como Rey y Reina de Breckenridge.

Las actividades del domingo rememoraron el Carnaval de Invierno original de Breckenridge, celebrado por primera vez el año anterior, con carreras de trineos tirados por perros y carreras de esquís en French Street. El Departamento de Bomberos Voluntarios de Breckenridge patrocinó los actos del carnaval.

Las descripciones del primer Ullr Dag promovían con entusiasmo su continuidad. Décadas después, en sus grabaciones para el Proyecto de Historia Oral de Breckenridge, los veteranos aún lo recordaban. "Fue una época salvaje e histérica", recordaba Kay McGinnis. "Los días más salvajes", recordaba Bob Atchison. "Una locura", decían las hermanas Cope. "Fue muy divertido".

Con los años, Ullr Dag evolucionó. La hora del desfile cambió a horas diurnas. El Ullr Dag de 1964 introdujo un concurso de barbas. En 1965, se añadieron las carreras de Ski-Doo. En 1966, los jets supersónicos se lanzaron en picado para iniciar el desfile y actuaron los bailarines indios Koshare. El gobernador Love repitió su papel de rey Juan I varias veces. Larry Raff interpretó a Ullr de forma constante a lo largo de los años. Cada año asistía más gente a Ullr Dag. El objetivo de promocionar Breckenridge funcionó.

Aparecieron nubes negras en el horizonte con el Ullr Dag de 1966. Una vaga referencia en el editorial de un periódico apuntaba a "problemas con los chicos". Pequeños destrozos y el aparente consumo de alcohol por parte de menores de edad ese año presagiaron la debacle del Ullr Dag de 1967 , que supuso el fin de Ullr en Breckenridge. Pasaría más de una década antes de que Ullr fuera invitado a regresar a su reino.

Más información sobre los orígenes de Ullr y el final de Ullr Dag en el blog de la Breckenridge Heritage Alliance. Para más recursos sobre la historia de Breckenridge, visite el sitio web o el lugar histórico o la exposición, o haga una visita guiada.

Escrito por: Leigh Girvin