Trazado de las calles de Breckenridge

April 08, 2022 | Category: Historia de Breckenridge

Poco después de que los buscadores encontraran oro en lo que hoy es el condado de Summit, los campamentos mineros florecieron a lo largo de los cursos de agua y los barrancos. De aspecto similar, mostraban poca planificación u organización. Elegían un lugar cerca de la madera y el agua, y colocaban sus tiendas y cabañas de madera al azar en las minas o cerca de ellas. Sólo más tarde, cuando las reclamaciones tuvieron que ser inspeccionadas, se desarrolló cualquier apariencia de orden u organización. Apareció una calle principal, nada más que un camino entre tocones y rocas bordeado de tiendas y edificios rectangulares con fachadas falsas que anunciaban comida, ropa, bebida o provisiones.

Poco después de que los buscadores encontraran oro en lo que hoy es el condado de Summit, los campamentos mineros florecieron a lo largo de los cursos de agua y los barrancos. De aspecto similar, mostraban poca planificación u organización. Elegían un lugar cerca de la madera y el agua, y colocaban sus tiendas y cabañas de madera al azar en las minas o cerca de ellas. Sólo más tarde, cuando las reclamaciones tuvieron que ser inspeccionadas, se desarrolló cualquier apariencia de orden u organización. Apareció una calle principal, nada más que un camino entre tocones y rocas bordeado de tiendas y edificios rectangulares con fachadas falsas que anunciaban comida, ropa, bebida o provisiones.

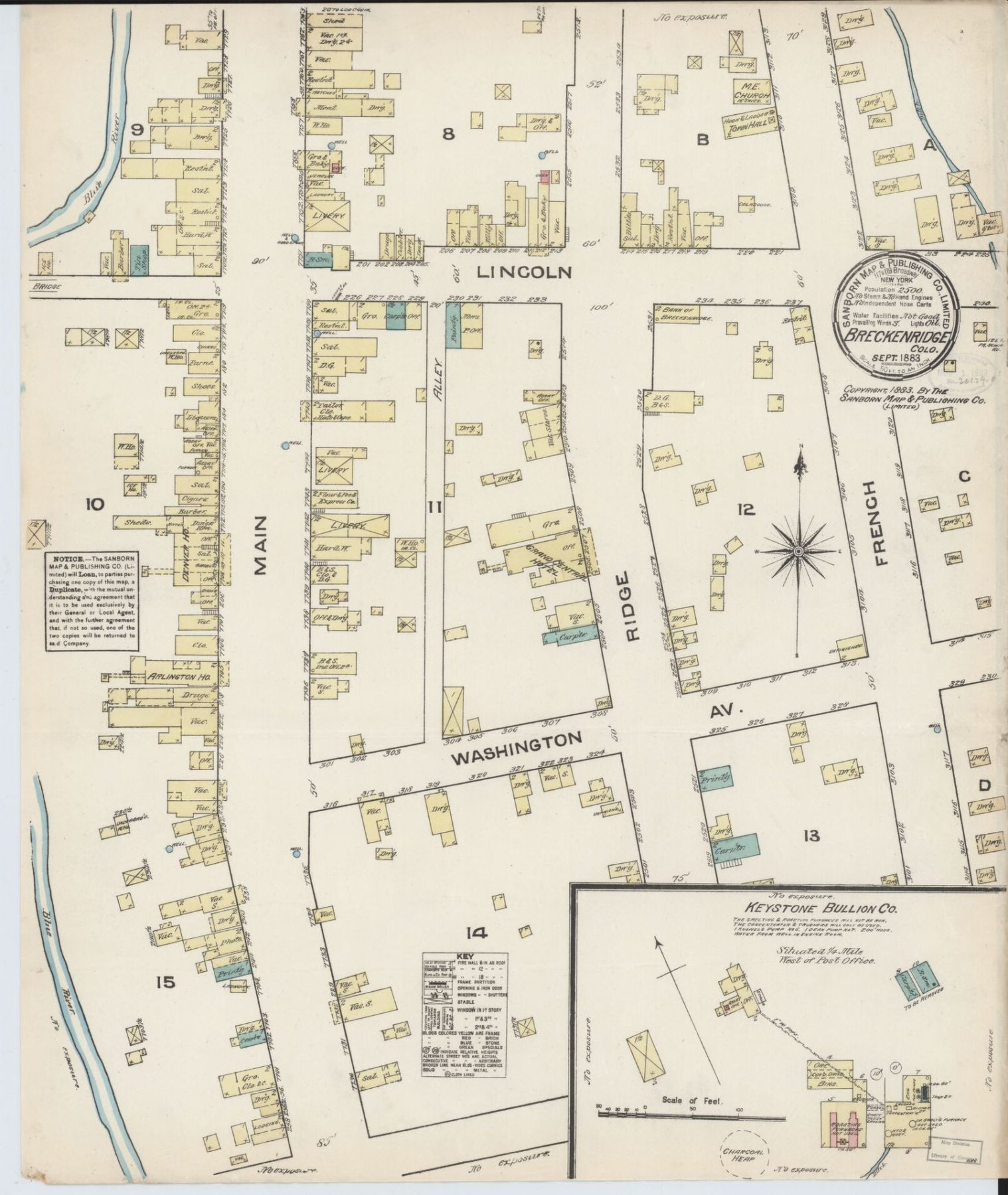

Los especuladores de tierras, que planeaban hacer fortuna ofreciendo lotes edificables en venta, trajeron la primera verdadera organización de calles y callejones a sus recién creadas ciudades. George E. Spencer y otros, bajo el nombre de Spencer, Humphreys, McDougal y Wagstaff, trazaron la ciudad de Breckenridge pocas semanas después del primer descubrimiento de oro en el río Blue. Los primeros mapas muestran que las parcelas de la ciudad se superponían a los yacimientos de Bartlett & Shock, Snyder, Abbett, Silverthorn, Fanny y Maggie.

El sistema de calles en cuadrícula prevaleció, al igual que en otras ciudades mineras. Los especuladores y topógrafos lo preferían, tanto si trabajaban en terrenos llanos como en terrenos con pendientes pronunciadas, porque era fácil colocar rectángulos en un mapa; su regularidad reducía el número de errores topográficos; ofrecía una gran variedad de disposiciones de lotes individuales dentro de una misma manzana; y la división del terreno podía hacerse sin necesidad de estar in situ.

Los negocios y las residencias se alineaban en Main Street, la calle principal original, paralela al río Blue. En 1866, Bayard Taylor describió la calle como una zona con "casas de troncos y señales de embarque", como el Miner's Home and Saloon. William Brewer, tres años más tarde, escribió que Breckenridge tenía "una sola calle de cabañas de un piso cubiertas de tierra en lugar de tejas". Señaló alojamientos primitivos en tiendas divididas que se anunciaban como pensiones. El Hotel Rankins tenía una sola habitación. En Main Street había otros negocios: restaurantes, caballerizas, oficinas de ensayo, herrerías y tiendas de suministros para la minería, comida y refrescos.

Las familias más adineradas de una ciudad minera solían vivir a una manzana de la calle principal, en un lugar elevado que dominara el resto de la ciudad. A principios de la década de 1880, ésta era la calle Ridge. El periódico comentaba que Ridge Street ocupaba "el terreno más alto del lugar, y las vistas del paisaje montañoso y del valle del río Blue son extraordinariamente bellas". El editor también explicaba: "La calle ocupa una posición central en la ciudad y es uno de los mejores paseos, así como una ubicación superior para residencias. Durante la última temporada se ha realizado un gran trabajo de nivelación, eliminación de rocas y tocones......". Pero no sólo se construyeron viviendas en Ridge Street. Añadió: "Ya se han instalado en ella uno de los principales hoteles, un banco, una oficina de prensa, una oficina de correos, varios salones y casas de negocios, con la perspectiva de que le sigan otros".

A medida que la ciudad crecía hacia el este, surgió un problema como resultado de la topografía de la construcción de lotes en los placeres ya existentes. En 1882, F.P. YIngling y P.D. Mickels, propietarios de la explotación de Bonanza, que se extendía desde el norte de Lincoln hasta ligeramente al sur de Adams, en el lado este de Harris, y que se extendía cinco manzanas hacia el este más allá de lo que entonces era el límite de la ciudad, subdividieron la explotación y notificaron a los propietarios de los lotes que debían comprar, alquilar o desalojar sus viviendas. La gente había comprado sus lotes y construido en ellos sin saber que tenían escrituras inválidas. Los precios fijados por Yingling y Mickels parecían exorbitantes en una época de precios inmobiliarios generalmente bajos. Los ocupantes de los terrenos se mostraron dispuestos a pagar el coste del solar sin mejoras. Yingling y Mickels consideraron que, como verdaderos propietarios, podían fijar el precio. Si los que vivían en el terreno no querían pagar el precio, podían marcharse. Desgraciadamente, el periódico no informó de la resolución de los dos puntos de vista opuestos.

Cuando el ferrocarril llegó a Breckenridge en septiembre de 1883, el "oeste" de Breckenridge cobró importancia. Los trenes entraban en el pueblo por la actual Boreas Pass Road, cruzaban Main Street hasta Park Avenue y se dirigían al norte, a Dillon. El ferrocarril construyó un depósito de pasajeros y mercancías en el lado oeste de las vías, así como una estación carbonera. Otras empresas situadas a lo largo de las vías aprovecharon el ferrocarril: la planta de luz eléctrica, un molino concentrador y un barrio rojo.

A principios y mediados de la década de 1880, las principales calles de Breckenridge reflejaban la verdadera prosperidad de la ciudad. Los establecimientos de Main, Ridge y las calles transversales incluían no sólo los habituales hoteles, pensiones, salones, tiendas de mercancías generales, caballerizas, oficinas de periódicos, bancos, herrerías, oficinas de ensayo y depósitos de transporte, sino también tiendas y comercios especializados: la casa de baños, la barbería, la droguería, la confitería, la papelería, la ferretería, la panadería, la modista y el sastre, el vendedor de botas y zapatos, los contratistas y constructores, el salón de música, la tienda de muebles, el fotógrafo, el pintor, el museo, las lavanderías y los despachos de abogados, aunque en general los abogados no eran deseados y se consideraban bastante innecesarios.

El sistema de cuadrícula sigue identificando las calles originales del distrito histórico de Breckenridge. Main Street conserva su función comercial principal; Ridge Street ofrece magníficas vistas de la cordillera Ten Mile Range. Sin embargo, mucho ha cambiado a lo largo de esas calles. Los negocios que reflejaban la economía minera han sido sustituidos por negocios basados en la economía recreativa dependiente del oro blanco (la nieve). ¿Y las propias calles que rodean la cuadrícula original? Ahora responden a las características topográficas en lugar de marchar a través de la tierra en los intervalos regulares del patrón de cuadrícula.

escrito por Sandra F. Mather, PhD