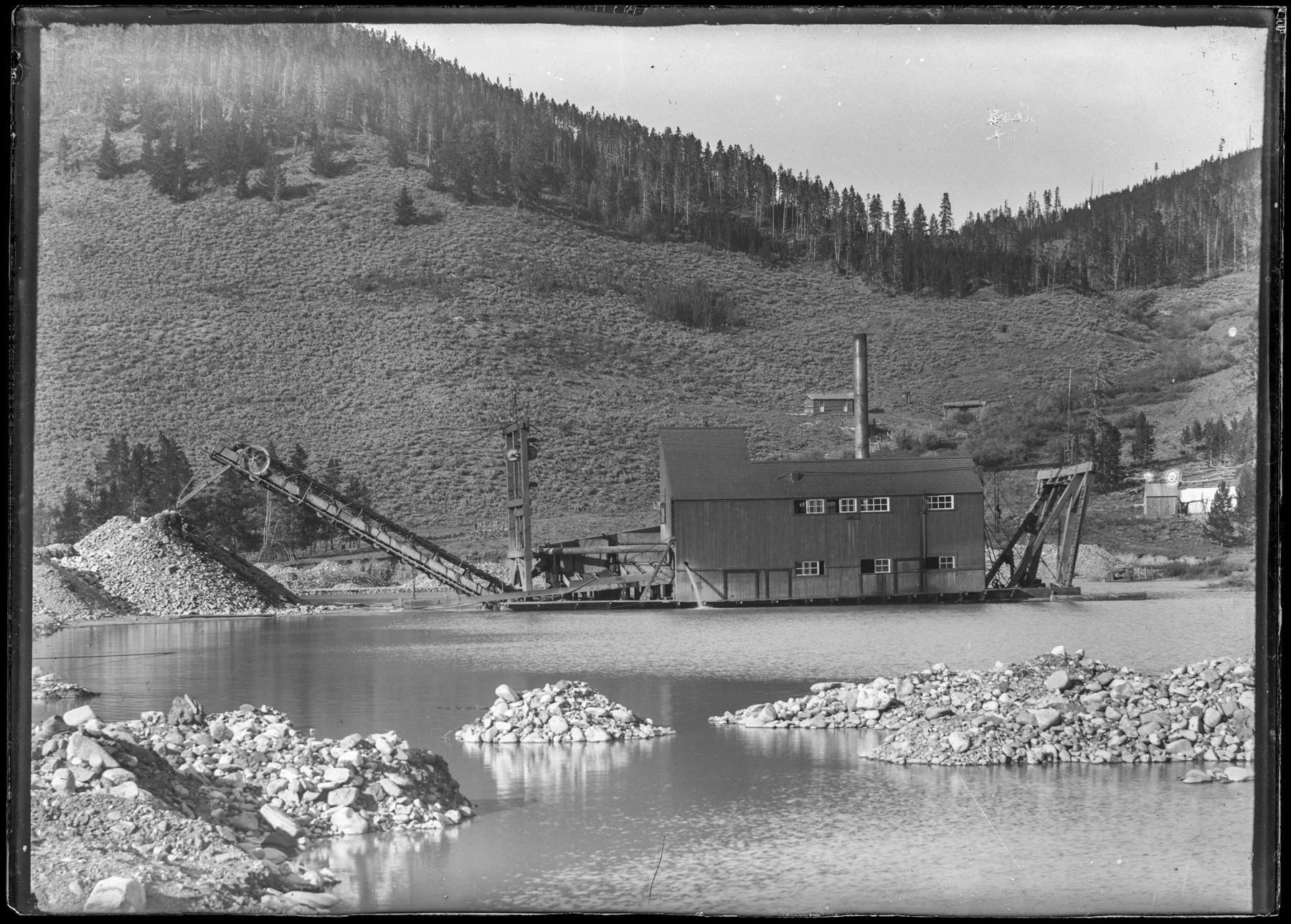

Barco draga minero en Breckenridge

April 08, 2022 | Category: Historia de Breckenridge

Breckenridge y el sur del condado de Summit experimentaron tres auges mineros. El primero, que duró desde 1859 hasta mediados de la década de 1860, atrajo a buscadores que buscaban el oro "fácil": las pepitas de los arroyos, las piezas que yacían en el suelo y las enterradas en terrenos poco profundos de las laderas. Utilizaban bateas, cajas de balancín, largos toms y, más tarde, mangueras de alta presión llamadas "gigantes" para lavar la tierra llena de oro y depositarla en las cajas de las esclusas. El segundo boom, el de la minería de roca dura, comenzó en la década de 1870. En lugar del buscador individual que perseguía su sueño, las empresas contrataron a mineros y a otras personas para trabajar en las minas. El tercer boom, impulsado por nueve barcos de dragado de oro, comenzó en 1898 y duró hasta 1942. Esta es su historia.

Breckenridge y el sur del condado de Summit experimentaron tres auges mineros. El primero, que duró desde 1859 hasta mediados de la década de 1860, atrajo a buscadores que buscaban el oro "fácil": las pepitas de los arroyos, las piezas que yacían en el suelo y las enterradas en terrenos poco profundos de las laderas. Utilizaban bateas, cajas de balancín, largos toms y, más tarde, mangueras de alta presión llamadas "gigantes" para lavar la tierra llena de oro y depositarla en las cajas de las esclusas. El segundo boom, el de la minería de roca dura, comenzó en la década de 1870. En lugar del buscador individual que perseguía su sueño, las empresas contrataron a mineros y a otras personas para trabajar en las minas. El tercer boom, impulsado por nueve barcos de dragado de oro, comenzó en 1898 y duró hasta 1942. Esta es su historia.

El dragado, el método de extracción que utiliza la mayor cantidad de conocimientos tecnológicos y energía y causa el mayor daño medioambiental, pone literalmente patas arriba los cursos de agua. Helen Rich, una escritora de Breckenridge, lo describió así:

"La draga está en cuclillas sobre un estanque marrón verdoso, y dondequiera que vaya la draga, también va el estanque. El agua procede de un arroyo de montaña cercano y es clara cuando desemboca en el estanque, pero no después. El barco dorado parece un monstruo prehistórico. Tiene una cubierta igual a la de cualquier otro barco, pero en la proa hay unos maderos con forma de cuello llamados pórticos. Sostienen la escalera de cubos, y la escalera de cubos sostiene los cubos de excavación. En medio del barco hay una joroba inferior que cubre la maquinaria. Esta maquinaria actúa como un estómago. Se alimenta de oro y expulsa lo que no quiere. Este residuo sale por una cinta transportadora cubierta de lona blanca. Durante todo el día, toda la noche, la cinta transportadora lleva todo lo que no es oro hasta la apiladora y lo deja caer. Splat. Plop. A medida que el monstruo avanza, deja tras de sí montones de residuos más altos que una casa de dos pisos".

Ben Stanley Revett trajo las primeras dragas a Breckenridge en 1898. Un total de nueve dragas de oro recorrieron los arroyos del condado, siete de ellas con el sello de Revett. Las dragas tuvieron un éxito variable, a menudo en función del tamaño de la embarcación: las tres primeras no tuvieron ningún éxito; la cuarta, un éxito moderado. Otras tres tuvieron éxito: una tuvo mucho éxito y dos tuvieron mucho éxito periódicamente, con una media de hasta 1.000 dólares diarios en oro recuperado.

Las dragas operaron en el río Swan, el río Blue y en French Gulch entre 1898 y 1942. En un momento dado, cinco dragas operaron simultáneamente en las tres vías fluviales.

El dragado en busca de oro comenzó en Nueva Zelanda ya en 1857. De allí, la idea llegó a Estados Unidos. Revett estudió por primera vez el dragado en Grasshopper Gulch, Bannock, Montana, en 1894. Al ver el éxito del dragado en Montana, compró y arrendó terrenos de dragado a lo largo del curso inferior del río Swan para sus operaciones.

La construcción comenzaba siempre con un gran foso que acababa llenándose de agua para hacer flotar la draga. El casco de madera descansaba sobre pilotes o troncos de madera apilados a varios metros de altura. En este punto, algunas empresas llenaban la fosa de agua para hacer flotar el casco. A continuación, los trabajadores instalaban el equipo y construían carcasas para proteger la maquinaria. Otras empresas construían primero la carcasa sobre el casco, luego llenaban la fosa de agua y, por último, instalaban el equipo.

Mientras que las primeras dragas funcionaban a vapor, lo que requería quemar enormes cantidades de madera o carbón en enormes calderas, los modelos posteriores funcionaban con electricidad.

Para estabilizar la draga mientras excavaba la grava, en las cuatro esquinas de la draga había unos gruesos cables de alambre llamados "tenders" que se extendían hasta la orilla, donde se enrollaban alrededor de un "deadman", un enorme tronco enterrado a un metro de profundidad y sujeto por grandes rocas. Las dragas posteriores tenían dos palos en la parte trasera de la embarcación. Hechos primero de madera pesada y más tarde de acero, los trabajadores los clavaban en el lecho del río para darles más estabilidad. Además, estos palos servían para hacer girar o pivotar la draga, dándole su característica forma curva.

A finales de 1897, Revett encargó la maquinaria de sus dos primeras dragas a la Risdon Iron Works de San Francisco. Medían 96 pies de eslora y 30 de manga, con cangilones de tres pies cúbicos de capacidad. Estos barcos de vapor, que quemaban madera como combustible, podían dragar 2.000 yardas cúbicas de grava cada 24 horas de funcionamiento. La empresa desmanteló ambos barcos porque sus cangilones no alcanzaban el oro del lecho rocoso del río Swan.

Revett contrató dos nuevas dragas en 1899: una de Risdon Iron Works y otra de la Bucyrus Company de South Milwaukee, Wisconsin. La tercera draga corrió la misma suerte que las dos primeras dragas Risdon. La draga Bucyrus comenzó a trabajar en agosto de 1899. Más pesada y más grande, de 110 pies de largo, propulsada por vapor, con una capacidad de 2.500 años cúbicos por cada 24 horas de funcionamiento, alcanzó con éxito el lecho rocoso. Trabajó en el río Swan desde 1901 hasta 1904.

La construcción de la quinta draga, la Reliance, comenzó en otoño de 1904, en French Gulch. Era enorme, pesaba 500 toneladas y medía 137 pies de largo y 37 de ancho. Costó 90.000 dólares y empezó a funcionar el 14 de julio de 1905. Fue una draga de gran éxito, con una media de más de 1.000 dólares diarios en oro. Primero funcionó con carbón y más tarde con electricidad, pero dejó de funcionar en 1920.

En 1907, Revett firmó contratos con la empresa Bucyrus para dos nuevas dragas de propulsión eléctrica. La sexta trabajó en el río Azul de forma intermitente desde 1908 hasta 1942, mientras que la séptima draga operó en el río Cisne de forma intermitente desde 1908 hasta 1919.

La octava draga, la draga Reiling, operó en French Gulch desde 1909 hasta 1920. La French Gulch Dredging Company, presidida por H.J. Reiling, consiguió arrendamientos de propiedades a lo largo de la vía fluvial. Reiling compró 200.000 pies de abeto de Oregón para la draga. Las operaciones comenzaron en la primavera de 1909. La primera limpieza en mayo, realizada después de sólo seis o siete días de funcionamiento, dio como resultado unos 9.000 dólares en oro. Tras otra limpieza similar, la empresa envió 13.000 dólares a la Casa de la Moneda de Denver. Ésta y la draga Reliance, ambas bastante exitosas, siguieron su camino en French Gulch hasta que los beneficios cayeron drásticamente. Su total combinado probablemente alcanzó los 4,2 millones de dólares; 1,8 sólo para la draga Reiling. Esos 4,2 millones de dólares equivaldrían hoy a unos 375 millones de dólares.

Los restos de la draga Reiling descansan en el estanque donde la draga "murió" mientras trabajaba las gravas de la barra de un arroyo. En 1942 se desmontaron el interior y la maquinaria, y el metal restante se recuperó para la guerra. La nieve y los rayos han hecho mella en la carcasa y el casco de madera. En 1911, la Alianza del Patrimonio de Breckenridge erigió señales interpretativas en el emplazamiento de la draga Reiling y construyó senderos para acceder a ella desde la carretera de French Gulch. Proyectos posteriores han estabilizado los restos.

La novena draga, construida por la Yuba Dredge Company de California, operaba en el río Blue. Con una longitud de 130 pies y una anchura de 42 pies y 8 pulgadas, con 87 cangilones, cada uno de los cuales contenía ocho pies cúbicos de grava, tenía una capacidad de 4.000 yardas cúbicas por cada 24 horas de funcionamiento. Dejó de funcionar el 13 de abril de 1938, cuando la Stearns Investment Company ejecutó la hipoteca de la draga. Los propietarios desmantelaron la draga y la trasladaron a Fairplay, en el condado de South Park.

La mayoría de la gente considera que las pilas de dragado, esos enormes montículos de roca redonda que aún se ven en los valles de los ríos Swan y Blue y en French Gulch, son una pesadilla medioambiental. Otros los ven como un recordatorio de las grandes dragas y de su capacidad para mantener Breckenridge vivo durante tantos años, cuando muy poca minería sostenía la economía del condado de Summit.

Tenían un apetito voraz por el combustible y la grava. Las primeras dragas necesitaban un suministro constante de madera como combustible. Los modelos posteriores utilizaban carbón y luego electricidad. Los barcos sucesivos aumentaron de tamaño y de capacidad de dragado. Las primeras, que resultaron demasiado pequeñas, medían 96 pies de eslora y 30 de manga. El último casco construido medía 130 pies por 42 pies y ocho pulgadas. Las dos primeras dragas excavaban 1.000 yardas cúbicas de fosa por cada 24 horas de funcionamiento; los modelos posteriores podían excavar hasta 5.000 yardas cúbicas.

Las operaciones de dragado no habrían sido posibles sin el ferrocarril. La draga Reliance en French Gulch, que pesaba 5.000 toneladas cuando estuvo terminada, necesitó 40.000 pies de madera de Oregón para su construcción. Sus calderas pesaban 11 toneladas cada una.

El mayor problema de las dragas era su incapacidad para llegar al lecho rocoso, donde el oro se había acumulado durante siglos. La profundidad del lecho rocoso variaba de un lugar a otro: algo más de 12 metros en el río Swan y bastante más de 15 metros en algunas partes del río Bluie.

escrito por Sandra F. Mather, PhD