New Research on Barney Ford Changes the Story Again

June 09, 2021 | Category: Making History Happen

Breckenridge’s Barney Ford rose from enslavement to prominence and wealth, credited with being a founder of the State of Colorado. Yet the full picture of his life is far from complete. Mr. Ford left no personal records. Were it not for the beautiful home he built in Breckenridge around 1882 and that survives today as a museum, there may be no recollection of Barney Ford’s presence in Breckenridge at all. In honor of Ford’s upcoming 200th birthday, the Breckenridge Heritage Alliance (BHA) is reexamining sources and stories to create a more accurate picture of the incredible Barney Ford.

Few primary source documents exist to tell of Mr. Barney Ford. The earliest biography is found in Frank Hall’s History of the State of Colorado (Volume IV, 1895). Ford is one of a handful of people of color included in this accounting of the illustrious men and women who created the Colorado we know today.

From Hall’s Biography Section we learn that Barney Ford was born in Virginia on January 22, 1822, was “entirely self-educated,” was raised on a plantation in South Carolina, and in 1848 “went to Chicago and engaged as a barber.” Nowhere does Hall state that Barney Ford was African-American or that he escaped enslavement to find his freedom in the north. To conclude Ford’s biography, Hall sings high praise, noting that Ford was “respected by everyone,” commenting on his honesty, reputation, and wealth. Hall included an illustration of the Breckenridge house that Ford built, increasing our understanding of the home’s architectural and historical significance.

Much of Barney Ford’s life is unknowable. Despite his fame and fortune, Ford lived outside the glare of publicity. During his lifetime, his story is told in a few newspaper articles mentioning his doings and whereabouts, and in the advertisements he purchased for his businesses. Census data fills in many additional details.

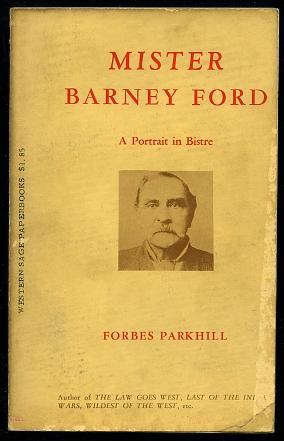

Barney Ford was gone from this earth for over sixty years before the first biography of his life was written. During the burgeoning civil rights movement of the late 1950s and early 1960s, a Denver-area writer of history, Forbes Parkhill, reignited Ford’s memory.

In 1963, Parkhill wrote Mister Barney Ford, A Portrait in Bistre (bistre is a brown pigment used as a wash in pen and ink drawings). Holding up Ford as one of Colorado’s successful black men from the 19th century, Parkhill capitalized on the growing interest in the mid-20th century in Black American history and civil rights.

Parkhill was a respected writer of history in Colorado. Carolyn Bancroft, one of the state’s famed historians, praised him and sought praise from him. Parkhill’s book on Barney Ford continues to be considered the best biography of Ford’s life, and is quoted and cited in every work that follows.

Yet Parkhill was a sensationalist. His popular titles include The Wildest of the West and Donna Madixxa Goes West: The Biography of a Witch. He wrote for pulp fiction magazines and movie screenplays. Many of his stories are embellished and fabricated, blurring fact and fiction.

Today, BHA considers Parkhill’s book Mister Barney Ford to be a fictionalized biography. Stories of Ford’s life that are taken as fact still today – such as his method of escape to freedom from a river boat, the name and background of the people who enslaved him, or his use of algebra to make decisions – can only be from Parkhill’s imagination; there were no known primary sources for these aspects of Ford’s life available to Parkhill.

The second book written on Barney Ford’s life is adapted directly from Parkhill’s with extensive credit to him. Inez Hunt, commissioned by Colorado Springs Public Schools, wrote Runaway Slave: The Adventures of Barney Ford in 1969. She is the most honest of Ford’s biographers, admitting in the notes that much of the text was made up. In her book, Ford’s story is simplified to appeal to the young readers of the school system. Like Parkhill, she addressed the new interest in civil rights and African-American heritage.

A few years later, Ford’s life was chronicled again by Marion Talmadge and Iris Gilmore in Barney Ford, Black Baron, published in 1973. Black Baron is a near copy-paste of Parkhill’s book. Reading the books in succession, as this author did, feels like déjà vu. The structure, storyline, even complete paragraphs are nearly identical to the Parkhill book.

That the authors acknowledge Parkhill’s assistance (“he gave us much good advice”) indicate that they had his blessing. Perhaps Gilmore and Talmadge obtained some kind of permission from Parkhill to alter the fictionalized sections of Barney’s life, such as the names of his owners, or how he escaped enslavement, as these are stories that differ from Parkhill’s account.

From the Black Baron book, legends continue to be regarded as fact today. There is no historical basis for their claim that Barney’s second owners were Quakers, or that he escaped from a riverboat dressed as a woman with the assistance of a sympathetic actor named J. Anthony Preston. As with Parkhill and the honest Hunt, many of these assumptions of Ford’s life are taken from the historical record, stories that happened to other people.

Our modern era of digitization allows easier access to historic documents, providing us with information that the early biographers did not have. Only recently have we learned of a letter written by Ford in 1848 and published in 1850 by the Chicago Western Citizen newspaper. The letter — written in his own hand to his owner of the previous five years, Nathaniel G. Woods — casts a new light on our understanding of Barney Ford.

On his departure from Woods, Ford wrote “it can’t be said that I have run away from you.” Ford stated that for the past five years he had worked without pay, without any new clothes, and had been required to sleep on the floor when they traveled. “I have left you without a dollar in my pocket, and I sink or swim, I shall depend on my own exertions for a living.” Learn more about Ford and the extraordinary letter in this article in Forbes Magazine.

Even before hearing Ford’s case for emancipation, the BHA has not used and does not use the term “runaway slave.” Hunt entitled her book “Runaway Slave” for reasons unknown today. Identifying any emancipated person as a “runaway slave” categorizes them as less than human, a mere fugitive, enabling some to say “he’s just a runaway.” The BHA employs equity in storytelling; as one example, we do not use the noun “slave,” instead we refer to the “enslaved person.”

It is possible that Ford did not escape from a Mississippi Riverboat at all. According to the published letter, Woods brought Barney to Quincy, Illinois, apparently on business, and stayed there for at least 10 days. Ford’s letter acknowledges the laws of that state: “If a man brings his slave here and remains in the State 10 days, that the slave is then free. So, with this on my side, I don’t think that I have done wrong in leaving you.”

Should the day come that the BHA writes a new book on Barney Ford, we will have to include a chapter called: Stories We Used to Tell. In it, we’ll debunk the old tales and share the accurate information that we continue to discover. One example is the origin of Barney’s last name. According to Parkhill, Barney and his wife-to-be Julia chose “Lancelot Ford” after a steam locomotive. The producers of PBS’ Colorado Experience episode on “Barney Ford” informed BHA that the Lancelot Ford locomotive hadn’t been invented in 1849 when Barney and Julia married. And now we know, from Ford’s letter of October 1848, he used the last name “Ford” at that time, well before he met Julia. Parkhill made up this entire naming story. And this is just one example. Most of the biography that stands for the truth of Ford’s life, and that every subsequent biography was based on, must be considered unreliable today.

For more information about Ford and his legacy, visit the Barney Ford House Museum. To learn more about Breckenridge history, visit a museum, join a guided tour or hike, or read our history articles and blogs.

written by Leigh Girvin