Our Collective History: Confronting difficult histories

April 27, 2023 | Category: Our Collective History

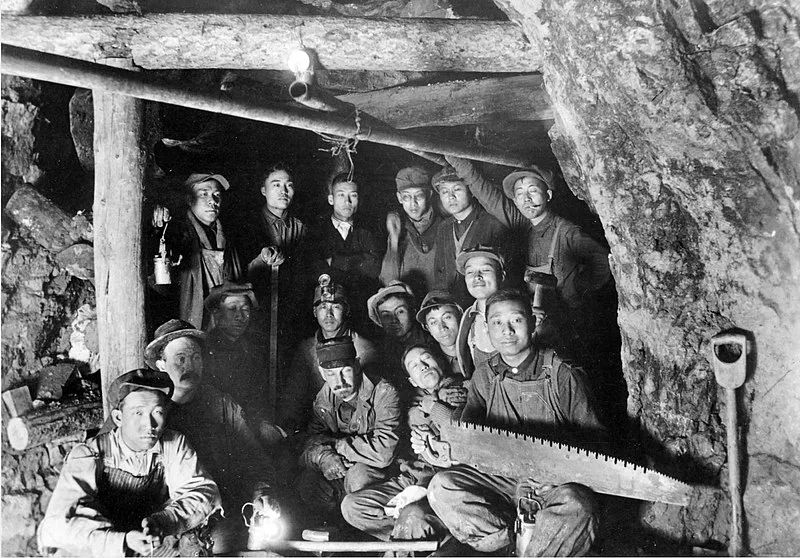

Chinese miners at a mine entrance in Idaho Springs, circa 1920s. We have no known photos of Chinese residents of Breckenridge from the mid- to late 1800s. Courtesy: Denver Public Library

One of our new blog post categories is Our Collective History, but what does that really mean?

When we think about history, there are specific events, ideas, and people who have helped to shape eras and places in time. These moments create our collective history. Things like, where were you on September 11th or when JFK was shot become part of our personal narrative. While the event itself is our collective history, the experience, effects, and even trauma, extending from them are completely unique to each individual.

When I was a little girl, my mom and I would pop in a cassette tape and sing at the top of our lungs driving up to Breckenridge from Denver. I remember one time when Garth Brooks’ “The Dance” came on, my mom got really quiet and before the song was over she was sobbing. I didn’t understand what had just happened. I didn’t understand how this song, this experience, could be so different for both of us, but that is because I didn’t know her story. I didn’t know what was going on in her life that made those words so powerful for her that day or what memories were replaying in her mind as Garth crooned along. Shortly after my mom passed away, I was driving up from Denver with my niece when “The Dance” streamed through my speakers via Spotify, and it was my niece in the passenger seat looking at me with complete bewilderment as to why there were tears rolling down my cheeks.

This same principle applies to history on a much larger scale. When we think about the mining booms in Breckenridge, it is one thing to tell the story of people coming from far and wide to try to make their fortune in these mountains, but it’s something entirely different to look at the individuals. Why did they come here? What made them decide this was a risk worth taking? Did they have a choice? And what about the people who already lived here? Was this a good thing from their perspective?

As historians, we often find ourselves trying to cobble together a story of what happened based on the records we have available, but the records that get saved don’t always reflect society as a whole. It’s in these moments that history can get uncomfortable. But as part of our effort to talk about Our Collective History, we are not going to shy away from these moments.

We know that Mrs. Briggle – a society woman, member of the Episcopalian Church and music teacher – experienced Breckenridge in a very different way from Lizzy Cassidy – a wife and mother who had to turn to prostitution after her husband was jailed for murder. But both of these women had real, honest experiences in this town and their stories are equally worth sharing. With that in mind, let’s hop into a story that might not show the best side of Breckenridge and our history.

Asian American History in Breckenridge

This month is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, and as our staff sat down to plan out content, we decided it would be great to have a blog post about Asian Americans who have called Breckenridge home. I sat down to research and write a blog post hoping that I would find one historical figure who would be my guiding light through the Asian American experience in historic Breckenridge.

I was hoping to find that rags to riches story of a miner who struck out to make it big, or a businessman who started from the ground up to become a tycoon. Unfortunately, that is not how my research played out. Instead, I ran into a number of problems. Chief among them: We don’t know much of anything about what Asian Americans’ lives were like here. We say things like “their story was lost to time,” but the truth is no one made an effort to preserve it. The diaries of Asian Americans who worked in the mines weren’t kept, nor were the records from their businesses or any other parts of their lives. In a way, this does tell us something about their stories, just not the details we hope to find.

One of my first steps when researching any story is to look at the old newspaper records at the time. However, this again points to the disparity in how people lived in Breckenridge. For someone like Mrs. Briggle, every trip she took to visit friends, or her husband took to go hunting, is documented in the newspapers. There’s an entire article about little Florence Watson’s seventh birthday party, but Asian Americans living here were just not written about in that manner.

This building at 102 N. Main St. was built in 1862 and housed Choy’s Chinese Laundry in the 1880s.

We know that a man from China, Choy, owned a laundry service in Breckenridge, and he is occasionally written about, but again, the language gets uncomfortable. An 1895 article in the Summit County Journal talks about Choy celebrating Chinese New Year:

“Chinese New Years came a month earlier this year than last. Perhaps the Japanese urged it ahead some … Chinese New Year was celebrated yesterday with all pomp, bomb and fire cracker enthusiasm incident with the Sons of Confucius’ fourth of July. The exercise began about 5 a.m. with a long roll of fire crackers being let off. Receiving visitors and treating followed through the day, interspersed with more fire crackers. Doc and Choy enjoyed themselves fully and had friendly greeting for all who called on them.”

While we don’t get the opportunity to learn much about Choy from excerpts like this, we can glean a little bit about the town and his experience. Another article about Choy celebrating Chinese New Year says that he and his friends celebrated “in their usual manner with offerings to their Joss and refreshments for their visitors.” Again, we can put on our detective hats here and see that there were multiple people living here and celebrating Chinese New Year together. We can also tell that the celebration was an annual tradition for Choy and that he was pretty inviting to others who wanted to celebrate. The fact that there was a celebration is a sign of at least some level of acceptance from other townspeople, but how the event is written about, clearly shows the limit to that welcoming nature.

Additional articles only further highlight the racism that was part of everyday life for Asian Americans at the time. An article from a 1906 Breckenridge Bulletin is a perfect example:

“Ta Wa, a Chinaman, was sentenced at Rangoon recently to five years of hard labor for stealing a bottle of whisky. They must have needed help in the laundry of the Rangoon penitentiary.”

The local newspapers also ran articles from across the country that included the same derogatory language, if not worse. However, this is a vast change toward inclusion when compared to articles that ran only a couple decades prior in the 1870s and 1880s.

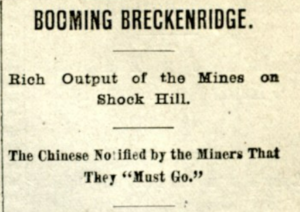

Fear Grips Breckenridge

In this instance, we don’t know the history for the individuals who were living here, but we do know the collective history that informed their lives. Based on Census records, we know there were 19 Chinese people living in Breckenridge and working in laundries in 1880. Articles from the Rocky Mountain News show Chinese people working in the mines here in the mid- to late 1870s, but by 1880 fear of what the Chinese laborers would mean for wages and work struck Breckenridge. An article in the May 20, 1880, Rocky Mountain News shows just how serious the issue became here:

“On Sunday afternoon a large public meeting was held on Lincoln avenue, when excited speeches were made on the Chinese question. The facts are that these people are coming in at the rate of eight or ten per day and the working miners fear an overwhelming influx that will reduce wages and ruin the camp. In the evening a crowd assembled estimatee (sic) at upwards of 1,500 men, when the almond-eyed foreigners were notified to leave. No violence was committed and none is anticipated, but the boys declare that the ‘Chinese must go,’ They are not wanted here and are depriving many a man and woman of honest labor.”

Beyond newspapers, legal issues and immigration policies were formed largely in response to encounters in the mining industry. Including here in Breckenridge where the citizens decided to take matters into their own hands with a resolution against Chinese immigration. From the April 17, 1881, Rocky Mountain News:

At a meeting of the citizens of Breckenridge held this evening the following resolutions were unanimously adopted:

WHEREAS, We the business men, miners, laborers and working men generally of the town of Breckenridge, county of Summit and state of Colorado, believing the importation of Asiatic laborers in large numbers to be detrimental to the interests of these United States, and

WHEREAS, Large numbers of Chinese laborers are about to be brought here by the companies to take the place of and do the work which of right belongs to the white race of the country, both male and female: therefore, be it

Resolved, That we, the citizens aforesaid, do protest against such importation of Chinese labor; and be it

Resolved, That the officers of this meeting be instructed to request the proprietors of all stage lines, freight teams, or other conveyances, not to carry such Chinese laborers to this vicinity, and be it further

Resolved, That the meeting appoint a committee to notify the agents of the several companies intending to employ such labor in this vicinity that such labor will not be tolerated in this community, and be it

Resolved, That the said committee also notify all resident Chinamen now residing here that their own toleration in this community in the future depends upon their co-operation with the citizens of this town and vicinity in keeping out all others of their race and nationality. Be it

Resolved, That a committee of five reliable men be appointed by the chairman of his own volition and at such time as he shall think best to act as an executive committee, whose duty will be to carry out the intent of these resolutions. Be it

Resolved, That we will not patronize any merchant, shop-keeper, saloon-keeper or businessman who employs Chinese labor for washing clothes or any other purpose. Be it

Resolved, That these resolutions be published in the Breckenridge papers.

Signed: H.J. Holmes, M.O. Sullivan, James R. Lewis and one hundred and seventy-five citizens.

The national landscape wasn’t any better. In 1882, President Chester Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited the immigration of all Chinese laborers. This followed the Chinese Massacre of 1871, in which 18 Chinese men were lynched by a 500-person mob in Los Angeles.

All of these events and this rhetoric informed Choy’s life here in Breckenridge. Yet we know he was able to become a successful businessman and community member. We just don’t know exactly what his community looked like or how he personally felt about these situations.

A Picture of the Past

So, what do we do from here? We know that we don’t have a full picture of what Choy’s life looked like, or what life was like for any of the other Asian Americans who were living in Breckenridge at the time. We may never get to see that full picture. But what we can do is tell the story that we have without glossing over the uncomfortable parts. Maybe by telling these stories, other people will come forward with their own histories or feel more comfortable sharing their family’s past experiences and traumas. Or maybe we just end up with a little bit more of the picture of what Breckenridge was truly like for each individual. Regardless, the story of every person who lived here helps to shape Our Collective History and that is a story worth telling.