Pressure, preservation, and the path forward

May 30, 2024 | Category: Making History Happen

When I was in graduate school at the University of Michigan, I studied archives and records management. One professor, Dr. Wallace, spoke to us about the “dark night of the soul.” We made t-shirts – a wolf howling at the moon encircled by the words “preparing for the dark night of the soul.” It became a crusade, a calling, and an ulcer waiting to happen. If you’ve worked in archives, museums, or historic site preservation, you’ve probably experienced the dark night, even if you didn’t know the term. If not, I’ll explain. We have more than 100 historical sites, and limited time, manpower, and money to save them. You stand as a guardian of the past, responsible for the future. The decisions you make today decide what gets remembered, and maybe more importantly, what gets forgotten. So, how do you choose? Is it the site in the worst shape that gets saved? The one that’s most accessible? The one with the most historical value, which opens up a whole other can of worms as you try to determine who it was significant to, was it significant at the time or now? And how do you decide what’s significant in the future? You think about all of these variables as you lay awake in the middle of the night hoping that you’ve made the right decisions. That is the dark night, but what is preservation?

When I was in graduate school at the University of Michigan, I studied archives and records management. One professor, Dr. Wallace, spoke to us about the “dark night of the soul.” We made t-shirts – a wolf howling at the moon encircled by the words “preparing for the dark night of the soul.” It became a crusade, a calling, and an ulcer waiting to happen. If you’ve worked in archives, museums, or historic site preservation, you’ve probably experienced the dark night, even if you didn’t know the term. If not, I’ll explain. We have more than 100 historical sites, and limited time, manpower, and money to save them. You stand as a guardian of the past, responsible for the future. The decisions you make today decide what gets remembered, and maybe more importantly, what gets forgotten. So, how do you choose? Is it the site in the worst shape that gets saved? The one that’s most accessible? The one with the most historical value, which opens up a whole other can of worms as you try to determine who it was significant to, was it significant at the time or now? And how do you decide what’s significant in the future? You think about all of these variables as you lay awake in the middle of the night hoping that you’ve made the right decisions. That is the dark night, but what is preservation?

Preservation is Historical Sites

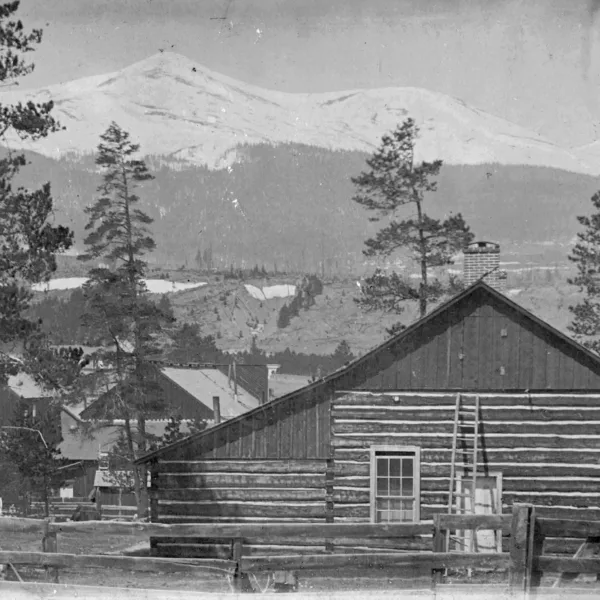

The Jessie Mill after a new roof was added to help preserve the site in 2023.

Here in Breckenridge, we are surrounded by our past. The Ute people walked for thousands of years on the same trails we walk today. Those same trails have been dotted with mines and mining equipment for hundreds of years. Even the museums here, like the Edwin Carter Museum, have existed for more than 100 years. Our past meets our present every day if you know where to look. Our job is to ensure that continues for our future generations to enjoy and learn from. If you’ve been here long enough, you might have stumbled upon the 1893 Jessie Mill in its prior state of decay. You might have even thought, “Someone should do something about that.” But what? Do you create a brand-new structure that replicates the past or save what’s still there? We chose both. After stabilizing efforts in 2015, we added a new roof to the structure last year to mimic the historical roofline. This summer, we’ll go back and remove the traces of our presence, so you can once again stumble upon the view of the Jessie, and maybe this time you’ll wonder, “Can you imagine what it was like working there?” Or give our interpretation panel a read to learn exactly what it was like.

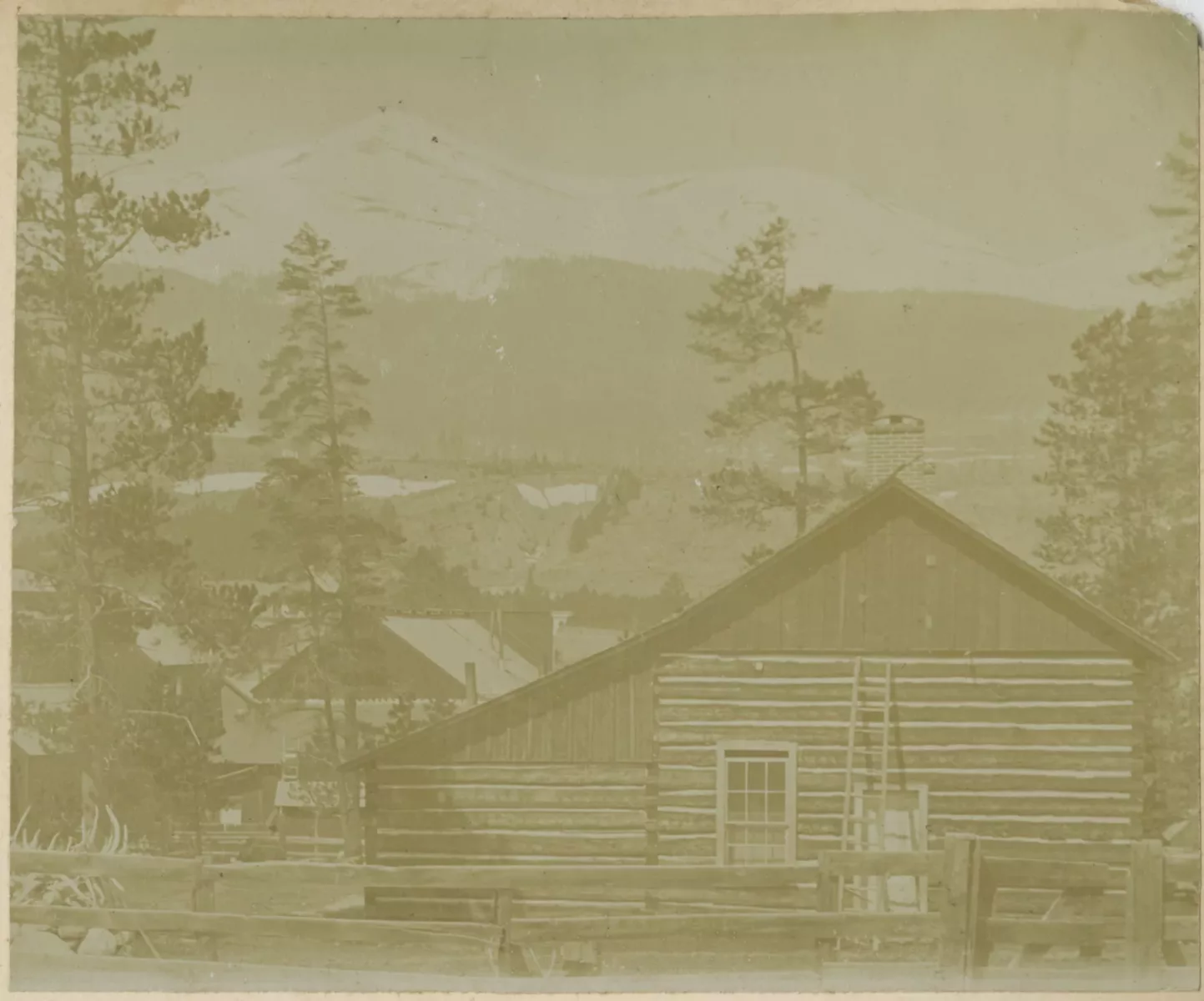

An original structure uncovered inside the Milne House.

There are other ways to preserve historical sites, as well. For example, look at Milne Park where Breckenridge History now has our offices and collections care facility. Two historical homes were preserved and transformed into usable space. These buildings now allow us to preserve artifacts from Breckenridge’s past and display them for public view. We also discovered a lot during our restoration process, including the original structure of an historical cabin and a cache of artifacts hidden in a wall – stop by sometime to see what we found!

Preservation is Access

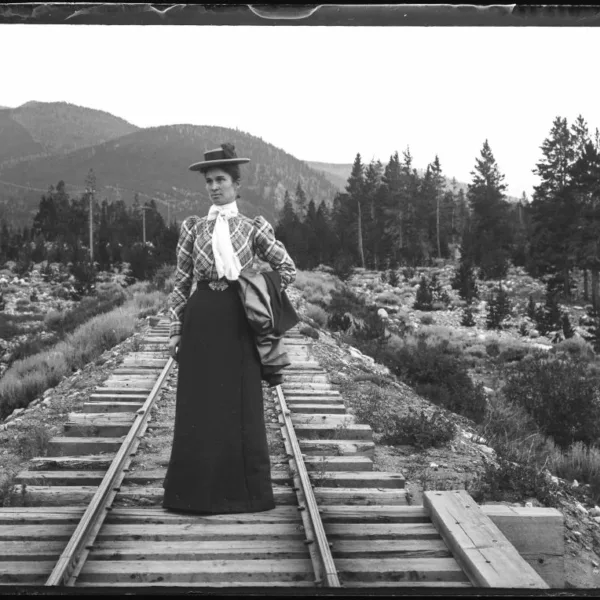

It’s wonderful to preserve our history, but what good does that do if no one ever gets to see it? When talking about access, you’re often looking at archival and museum collections – the objects of history. People want to see Otto Westerman’s photos from the 1800s and read Agnes Miner’s manuscript from the 1940s-50s. These objects become important not only because they’re preserved in safe conditions for future generations, but because you can interact with them right now.

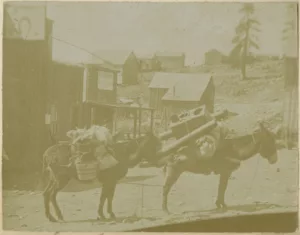

A miner’s pack (or jack) train loaded with supplies, including a stove. Two burros stand on a dirt road lined with wooden frame buildings.

Archival theory has changed a lot over the years. It used to be LOCKSS – Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe. You might be able to guess where there were downfalls to that. Then, Mark Greene, the director of the American Heritage Center in Laramie, Wyoming, introduced MPLP – More Product Less Process. This switch emphasized access.

When you get a collection there is a long list of things you have to do to stabilize it, record it, and prepare it for public access. Greene put an emphasis on getting through that process as quickly as possible to allow public access to collections. It’s still not a short process.

Maybe you have a basement full of family photos and diaries stuffed in various cardboard boxes and plastic bags. Maybe, you’re not even sure exactly what’s in there. When those items become an archival collection, they’re rehoused into archival boxes that prevent the material from degrading, they’re reorganized into a collection – or the collection must at least be cataloged in its current form – and thanks to all our modern technology, they’re digitized to create access copies.

We are very proud of the Breckenridge History Digital Archives which includes more than 1800 digital objects ranging from historical photos to oral history recordings and mine site inventories, all readily available from your computer at home or wherever you might be.

Preservation is Education

A guided tour at the Barney Ford Museum.

Education can take place in the classroom, but it can also take place on a hiking trail, a walking tour, or in a museum. Seeing an object is one thing, but hearing the story of why that object matters takes the experience to a whole new level.

Our Walk Through History Tour cuts right through the heart of Breckenridge and tell the stories of the people and places that helped to create our town. You can see historical photos of the buildings you’re standing in front of. On our guided hikes, you navigate through the physical objects of history while learning how and when they were used.

In the Barney Ford Museum, you literally walk into Ford’s 1882 home. His story lives in the architecture, in his words hanging on the wall, and in our interpreters as they tell you about his journey from being enslaved to becoming a businessman and civil rights leader. The same is true for the Edwin Carter Museum, which lives in his cabin – a museum that has existed for 149 years telling the story of our environment and our wildlife.

Those stories and experiences are preservation. It’s the storytellers’ version of LOCKSS. If we tell you the story, that story lives on with you, and maybe you tell it to someone else, and before we know it our history has been preserved through these experiences.

A guided hike at Iowa Hill is one part of our education programs.

With our educational programs, we try to spark that curiosity that makes our young people want to look for those stories. Maybe we bring in a train set and talk about all the different cars and all the different things they brought to our town – how they changed our town. This moment of playing with a toy can create a world of wonder for our students. Maybe from there, they’ll head over to High Line Railroad Park and see the trains that rode these rails. Or maybe they’ll remember the story of people who came here with nothing in the hopes of making a life here, and that will resonate because it touches on their own story. If we can get our future generations thinking about our history and their own story, that is preservation.