Learn about Ute history for National American Indian Heritage Month

November 13, 2023 | Category: Our Collective History

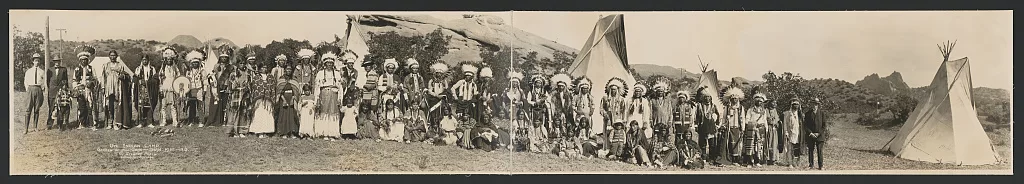

Ute camp in Garden of the Gods, Shan Kive, 1913. From the Library of Congress.

Since 1996, November has been celebrated as National American Indian Heritage Month. However, native heritage and the history of the United States and its interactions with native populations is unbelievably complex. At one time, 500 different native nations called this land home, but government policies and wars have destroyed some of those cultures and forced all the others to adapt.

Seasons of the Nuche exhibit at the Breckenridge Welcome Center.

Summit County is part of the ancestral homelands of the Ute tribe. At the Breckenridge Welcome Center, the Seasons of the Nuche exhibit is currently on display. Created in partnership between Ute elders and the Aspen Historical Society, this exhibit looks at the history of the Ute people through a seasonal lens. The exhibit is available to view during Welcome Center hours, 9 am to 6 pm, Tuesday to Saturday. Utes spent time hunting buffalo and other games in the Blue River valley and made use of the vegetation that grew here throughout the summertime.

According to the Ute creation story, this land has been their home since the beginning. They were chosen to live here by Sinawav, the creator, and thanks to Coyote’s curiosity, other tribes became their rivals. To read the Ute creation story as told by a tribal elder, visit the Southern Ute Tribe’s website.

Many tribes have their own creation stories which tell of sacred places, tribal values, and a tribe’s connection to the land. It is for this same reason that the Black Hills are considered sacred to the Lakota population. This is also why governmental policies of removal or relocation were so devastating for tribes.

The Ute tribe consists of several bands, which at one time ranged over all of Colorado, and parts of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah and Wyoming. Today, the Ute tribes occupy three reservations – two in southern Colorado and one in Utah. Yet, the way they navigated and lived on this land proved to be an invaluable resource for all the populations that came here after the Utes. For example, according to the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, what came to be known as the Spanish trail in the 16th century, was originally a Ute trail.

Past historical interpretations have claimed that the tribal nations that lived across the country were not well connected, but information from the tribes and archaeological digs have since shown that there was a complex society here long before European contact. Trails leading to large population centers as well as the variety of objects found at different tribal sites, have shown that trade between tribes was actually very common. Tribal nations had their own allies, rivals, and trade partners.

When European nations first made contact with native populations, the interactions were varied. For the Ute tribe, the first contact was with Spanish explorers, and later settlers. These interactions started out in a positive light with mutual trade between the nations. While there are conflicting views on whether horses pre-dated European contact, they did become an influential part of Ute culture after the Spanish arrived. According to Ute history, they were one of, if not the first, native nation to make use of the horse. This increased their ability to range across their lands in large bands and increased their hunting opportunities. As the Ute culture adapted and the significance of horses grew, so too did the interactions between Spanish settlers and native nations. With settlers continuing to encroach on Ute lands, many of the interactions turned hostile. This culminates in the first peace treaty between the Ute people and Spanish officials in 1670. Nearly 100 years later, around 1760, Utes granted Spain the right to trade along the Gunnison River, which was a precursor to massive trade routes yet to come. By 1811, Ute people had begun to encounter fur trappers in their lands, and by the time the Santa Fe Trail was established in 1821, large amounts of trade passing through Ute territory was commonplace. Over the next decades, trade was supported by the establishment of forts across Ute territory including Fort Uncompahgre, Bent’s Fort, and Fort Pueblo.

A group of Ute men and women in Colorado, 1893. From the Library of Congress.

With the end of the Mexican-American War in 1849, the Utes made their first treaty with the U.S. government. In the treaty, the Utes agreed to recognize the sovereignty of the U.S. nation, allow for the establishment of military outposts, and agreed to stay within territorial limits set by the U.S. government, while giving people of the United States free passage through Ute lands. However, 1849 is considered the start of the U.S. – Ute Wars. These wars consisted of a number of hostilities between different Ute bands and U.S. settlers across a wide range of land including Colorado and Utah. While there were numerous treaties established during this time, the wars weren’t officially concluded until 1923.

During this time, Colorado’s history made interactions with the Ute people even more complex. The Gold Rush in 1859 brought a much larger population to the state. The influx in population also brought an influx in disease. Between 1859 and 1879 the Ute population fell from 8,000 to 2,000 people. The establishment of Colorado as a territory (1861) and state (1876) only further fueled interactions between Ute people and settlers. In 1868, the Ute tribe was confined to the western third of the Colorado territory, and just a few years later in 1873, the Ute people were forced to cede a quarter of their remaining lands after gold and silver were found in the San Juan Mountains. As part of the agreement – it was not considered a treaty because the U.S. government did not recognize tribes as sovereign nations at the time – the chairman of the Board of Indian Affairs, Felix Brunot, was supposed to help Chief Ouray find his son, while giving the Utes hunting rights in the area and agreeing to pay the tribe annually.

At the time, the U.S. policy toward native nations had largely shifted to one of assimilation. The hope being that tribal members would give up their traditional lifestyles to become farmers and settle lands. One of the biggest supporters of this idea was Indian agent Nathan Meeker. Meeker pushed the Ute people to settle and a number of conflicts followed. In September 1879, Meeker requested federal troops to help secure his position. Seeing this as a threat, the Ute people rebelled, killing 11 people, including Meeker, and taking his family captive. The government wanted to hold the Utes accountable for the attack and requested Ouray bring 12 men to Washington, D.C., for trial. While the tribal members were acquitted, this was the catalyst that finally saw the White River and Uncompahgre bands removed from Colorado on a 350-mile journey to their reservation in Utah escorted by 1,000 troops. The Southern Utes stayed in Colorado.

All of this is just a small fraction of the Ute people’s history, though. The beauty of their people, culture, and traditions still lives on. The conflicts about the past and ways of life still live on. We can see the legacy of former policies like assimilation in many ways today. The fact that many native languages are dying out is a direct result. The loss of cultural identity caused by boarding schools and other policies still lingers today. But what matters most, is that the native population in the U.S. is still here. The best way to learn more about the Ute people is to connect directly with the tribe.

Here are some resources for further study: the Ute Indian Tribe website, Southern Ute Indian Tribe website, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe website, The Ute Indian Museum in Montrose, and the Southern Ute Cultural Center and Museum in Ignacio.

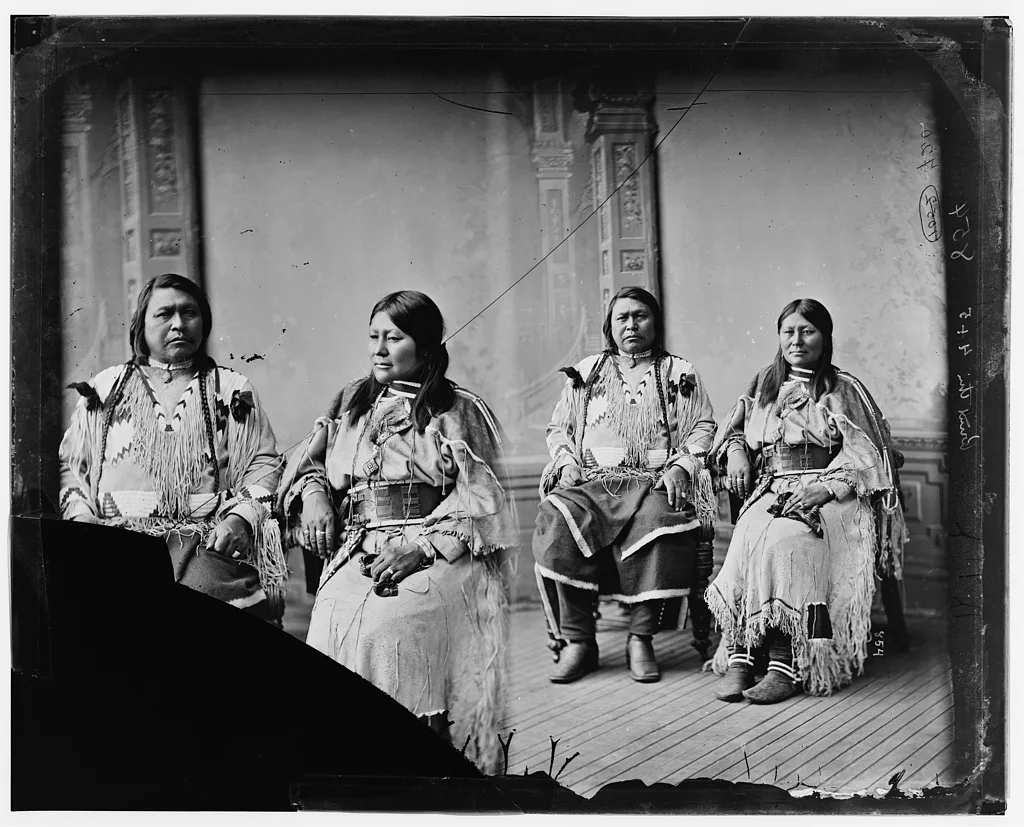

Chief Ouray and his wife, Chipeta. Circa 1880. Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.