Women of Willpower: Julia and Sarah Ford

March 03, 2022 | Category: Our Collective History

Mr. Barney L. Ford ascended to wealth and political prominence in frontier Colorado after a youth spent enslaved. The home in Breckenridge he built in 1882, now a museum, bears his name. But what about the women in his life? His wife and daughter who accompanied him to Breckenridge? In this article, the Breckenridge Heritage Alliance (BHA) explores the lives of Julia Lyons Ford and Sarah Ford Wormley, women of willpower who made a life for themselves and their families in the upstart communities of the West.

The Ford family arrived in Breckenridge in 1879. It was Barney’s second attempt at seeking riches in the gold camp; the boarding house he operated in Lincoln City famously entertained guests at a Christmas party in 1861. Down on his luck financially, Barney returned to Breckenridge to make another start by opening Ford’s Chop Stand at the corner of Main Street and Washington Avenue. With him in Breckenridge were his wife Julia, their middle child Sarah, and son Louis. Though in their twenties, the adult children made the move to Breckenridge and continued to live with their parents. At the time, eldest daughter Frances was in California with her husband and son.

As with most women of the Victorian period, we learn about Julia Ford through the news of her husband. Very few primary sources exist with information about Julia. What we know of her is gleaned through census data, the probate record settling her estate, and the very few newspaper articles that mention her.

A fictionalized biography of Barney Ford, Mr. Barney Ford: A Portrait in Bistre, written in 1963 by Forbes Parkhill, takes great liberties with the lives of Barney and Julia. When he couldn’t find primary source information, Parkhill made up stories. Because the historic record lacked detail about Julia, Parkhill’s portrait of her cannot be trusted as fact. Recently revealed primary source research highlights the many fallacies of the Parkhill book.

Julia A. Lyons was born in Indiana on September 15, 1827, on free soil to parents who were not enslaved. Starting in 1880, the U.S. census started asking birth location of the parents of those enumerated. From this we learned that Julia’s father was born in Virginia. Her mother’s information is less clear as census data is inconsistent; she may have been born in Indiana, Ohio or Canada. When Julia was 22, she was living in Chicago where she met Barney Ford. Ford found his freedom the year before and made his way to Chicago with the help of the Underground Railroad. There he met agent Henry Wagoner and Henry’s wife Susan, who was Julia’s older sister. Barney and Julia married in 1849 in Chicago. By the time of the 1850 census taken in September of that year, Barney and Julia were 28 and 23 years of age respectively, and lived in Chicago near the Wagoners. Barney owned real estate worth $100 at the time. Their first child, Frances, was born the following year, in 1851.

According to a biography of Barney Ford written in his lifetime by General Frank Hall, Ford spent the years between 1851 and 1856 or ’57 in Nicaragua after an aborted attempt to reach the California gold fields. The BHA believes it is highly unlikely that Julia accompanied Barney on his journey to California for several reasons. At the time of Barney’s departure, Julia had infant Frances. Barney took a ship from the East Coast and likely was accommodated in steerage. Not only was it expensive ($150 per person according to advertisements of the time), it was a long and difficult journey with an unknown outcome. Julia had a significant support system of extended family in Chicago. Their second child, Sarah, was born in 1858, after Barney returned from Nicaragua. Lacking family journals, it is impossible to know what Julia did in the years that her husband was absent.

Possessed of gold fever, Barney came west again with the “Pikes Peak or Bust” prospectors, arriving in Denver in May of 1860. Barney was in the gold fields when their third child, Louis, was born on July 2nd in Chicago. Julia’s arrival in Colorado with the children is undocumented.

The entire Ford family lived in Cheyenne, Wyoming, at the time of the 1870 census. The younger children, Sarah then age 12 and Louis age 9, were in school. Eldest daughter Frances, age 18, was married to John F. Jones who worked as a steward in Barney’s hotel. They and their six-month-old baby lived with the Fords.

Newspaper accounts document Barney Ford’s life in Cheyenne, but not Julia’s. Therefore, we can only assume that she fulfilled her roles as wife, mother, grandmother, and helpmate.

The Fords returned to Denver by 1871. Barney ascended to prominence in the 1870s in Denver, running for a seat in the territorial legislature and growing his hotel and restaurant businesses. By the mid-1870s, Barney Ford was a very wealthy man. Yet only a few years later, business losses and setbacks sent him searching again for the next opportunity. He hoped to find it in California, where Frances and John had relocated. But it was Breckenridge where Barney Ford made his comeback.

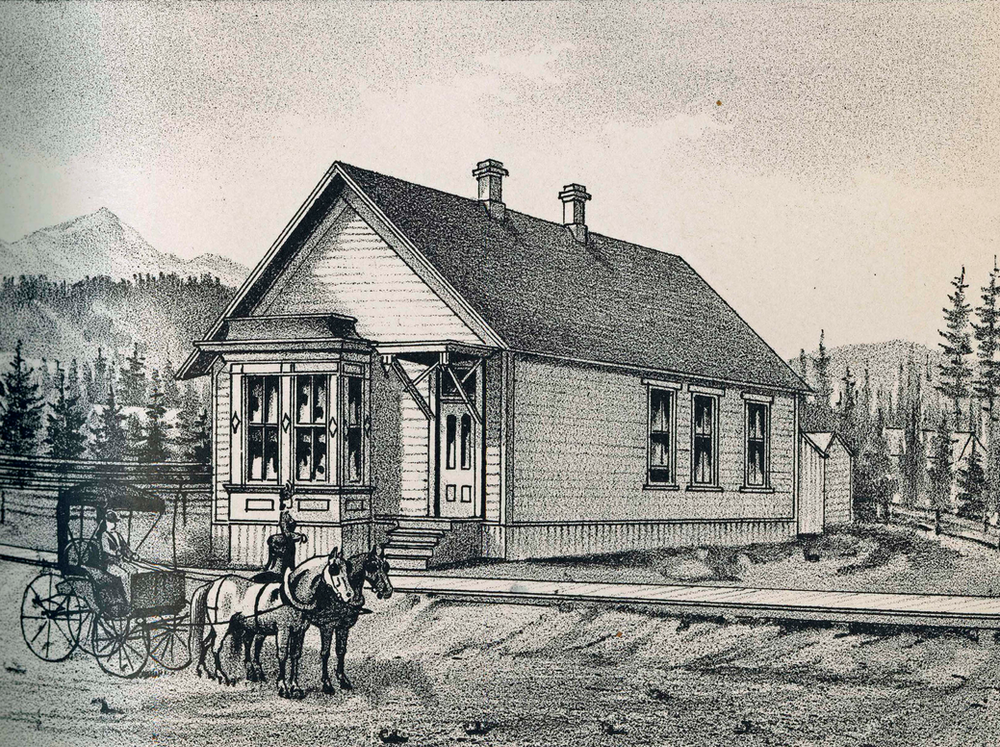

The 1880 census shows the Ford family together in Breckenridge, with son Louis, then aged 20, helping in this father’s restaurant, and daughter Sarah, then age 22, “without occupation.” Julia was keeping house. Their home at the time was the Photo Shop building at the corner of Main Street and Adams Ave. Not long after, Julia and Sarah were living in Denver. We know this because, in 1883, a significant event brought Julia and Sarah back to Breckenridge. According to a blurb in the Breckenridge Bulletin newspaper, on July 31, 1883, Barney Ford returned to Breckenridge with his wife and daughter who had been “residing in Denver for some time.” The newspaper described what happened: “We are glad to state that Miss Ford’s injuries, from the late deadly assault made on her in Denver, are not considered so serious as at first supposed, accounting only to a slight scalp wound.” In 1884, Sarah Ford was gone from Colorado, visiting in Rockford, Illinois.

Colorado conducted a census in 1885, revealing that the children were on their own. Barney and Julia occupied the house that is now a museum located at 111 E. Washington Avenue in Breckenridge.

In 1890, Barney and Julia left Breckenridge and returned to Denver, building or buying a home at 1569 High Street in the Capitol Hill area. Real estate records identify the house as built in 1890. Julia experienced joys and woes during the 1890s. Sarah married in 1892. Frances died in 1897. And son Louis was in and out of prison. Further research is needed to learn more about Louis’ criminal past, but it appears that he had a problem with theft.

The year before she died, Julia was listed in the Denver Social Year-Book, a “directory of the men and women who make up the social and club life of Denver with a complete membership register.” Julia is listed as residing at the home on High Street. Considered a great honor, Julia was the first, and likely only African-American woman listed in the esteemed volume, for many years.

On May 2, 1899, Julia died. It took a year for her estate to be cleared from probate. It appears that Julia owned the house on High Street and it had fallen into disrepair in the nine years since she and Barney moved in. The estate incurred significant bills fixing up the house, replacing the roof, repairing the boiler, and making improvements including paint, wallpaper, varnish, window screens, and more. Julia also owned a commercial property at 1313 15th Street that included shops, storage and rooms to rent.

In 1900, the census shows Barney living in Denver with Henry Wagoner, also a widower. Barney Ford would pass in 1902. Son Louis died in 1904. Barney, Julia and Louis are buried in adjacent sites in Denver’s historic Riverside Cemetery.

Daughter Sarah was in Denver in the days after her mother’s death, signing a waiver of service regarding the will on May 10, 1899.

We know almost nothing of Sarah’s life as an unmarried woman. It appears that she diligently followed her parents’ moves. Her mother stayed in Denver with her as a young adult. When in her twenties, Sarah visited friends in Illinois. Biographers imagined her singing in the choir in Breckenridge’s Methodist Church (later known as Father Dyer M.E. Church), which is a possibility. The Fords were involved with the Shorter African Methodist Episcopal Church in Denver. Biographers also imagined that many men asked for her hand in marriage, some only to tap into her father’s wealth. But this is merely speculation. Sarah’s young life is a mystery.

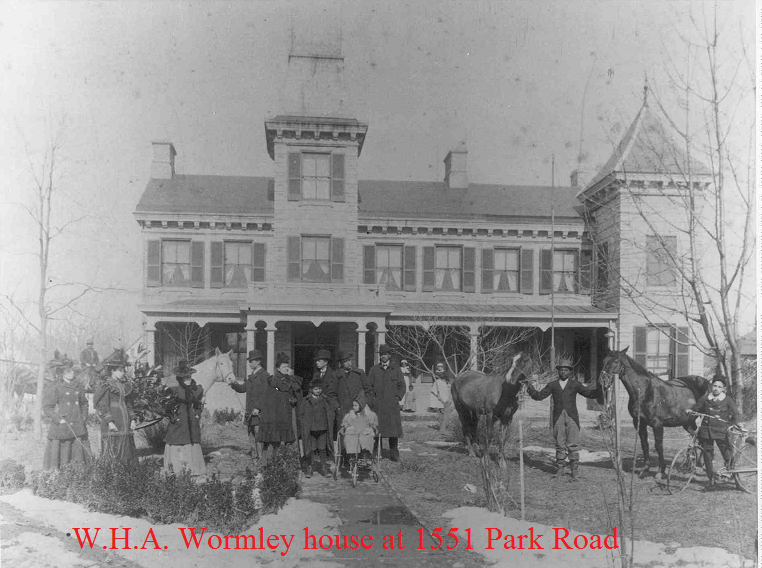

In June 1892, at age 34, Sarah married in Denver to a wealthy hotelier from a prominent African-American family from Washington D.C. Her husband, William H.A. Wormley, then age 50, was the son of James C. Wormley, proprietor of the famed Wormley Hotel on Lafayette Square near the White House.

The parallels between Barney L. Ford and James C. Wormley cannot be ignored. It is unknown when they met, but their lives followed similar paths. Ford’s Inter-Ocean Hotel in Denver looks uncannily like the Wormley Hotel on Lafayette, which was completed only a few years prior. Their political involvements overlapped and they knew many of the same prominent abolitionists of the time. W.H.A. Wormley’s daughter Miriam spoke of the friendship between Barney Ford and her grandfather. The BHA feels it is safe to assume that Barney had something to do with his daughter meeting William H.A. Wormley, the son of his friend.

Thanks to the Wormley family archives generously shared with BHA, we have been able to piece together significant information about Sarah’s married life. She married into wealth. William H.A. Wormley’s mansion in Washington, D.C. was statelier than any home she had lived in with her parents. The Wormleys were popular in D.C. social circles and knew everyone who was worth knowing, from presidents to senators, ambassadors, business leaders and visiting royalty.

William himself was a man of considerable accomplishments. He grew up in the hotel business with his father and brothers, learning the importance of associations. His first wife was the daughter of the valet to President Abraham Lincoln. When William assaulted an agent promoting passage to Liberia for recently emancipated slaves, Lincoln pardoned him (but still made him pay the fine). William volunteered for the First Colored Troops in Washington, D.C., and worked toward abolition and later for integration. He was an honorary pallbearer at Frederick Douglass’s 1895 funeral, served as a school board member, and later as a U.S. Marshal.

During her marriage, Sarah returned to Denver in 1904 to contest the will of her ne’er-do-well brother Louis who had left her $1 of the estate he received from their father. In his final months, between his last release from prison and before he died, Louis spent $1,000 in “carousing.” Sarah’s efforts were unsuccessful as an appeals court awarded the bulk of Louis’ estate to his common-law wife Clara Isom in 1905.

Note to history nerds: Clara Isom, who eventually won the estate, claimed to be LN Ford’s common-law wife. LN Ford left her $100 in his will. According to the article about Sarah contesting the will, Clara Isom is from St. Louis. Yet the claim that prompted Sarah to return to Denver to contest the will was by a Mrs. Belle Pruess, who claimed to be LN Ford’s fiance. Didn’t Louis weave a tangled web in his life! There is enough info on him for another article.

The post-Reconstruction era was hard on the Wormley family fortunes. In 1897, William sold the fabulous house on Park Street, which was torn down and the property subdivided. In an oral history shared by his youngest daughter Miriam, Wormley’s finances declined through his final years and he sold off many properties before his death in 1908.

Now a widow, Sarah managed on her own, relying on the solid work ethic she inherited from her father. Business directories from the early 1900s identify her as a dress maker. Step-daughter Miriam recalled that “Mother Sadie” was a charwoman (cleaning lady) after William’s death. The 1920 census tells that Sarah was working at a dry goods store.

Sarah passed at age 66 in 1924 in Washington, D.C. Her will remembered her “beloved husband” William and bequeathed her estate to his youngest two children, Miriam and Lawrence, “whom I reared from babies and look upon as my own.” And her estate was sizeable, despite the family’s economic decline. In addition to clothes, silverware, diamonds and furniture, she owned real estate in Washington, D.C. worth over $9,000. However, Sarah’s last will was contested by cousins living in California. The final disposition of Sarah’s estate is unknown, though step-daughter Miriam did not maintain a relationship with Sarah after William’s death.

Julia and Sarah Ford exemplify the resilient, ever-flexible women of the west who overcame adversity to do the very best they could. Both women worked, contributed to their families, fought injustice, owned real estate, and left estates of note. Their contributions fill out our understanding of the Ford family of Breckenridge.

To learn more about Breckenridge’s history, visit a museum, take a tour, or read our blog articles.

Written by Leigh Girvin