Father Dyer and Dyersville Ghost Town

September 10, 2021 | Category: Our Collective History

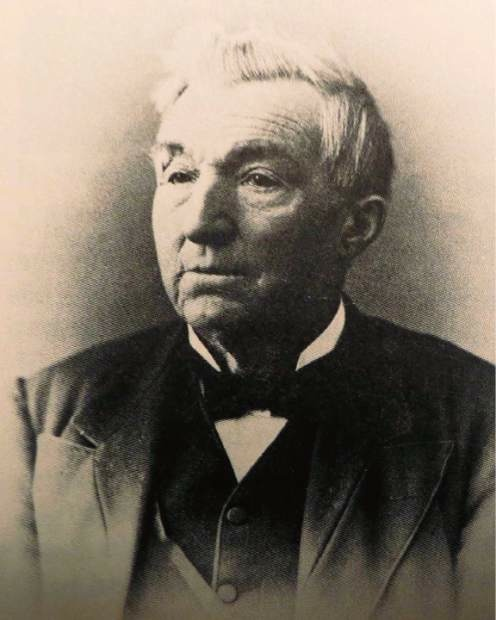

Father John Dyer preached the Methodist ministry across the Colorado frontier, bringing civilization to Breckenridge and other rough mining camps. Dyer returned to Breckenridge again and again in his long career, starting with his earliest days as a prospector-minister, to his final years as a revered religious leader and knowledgeable miner. Today, a local church and nearby ghost town still bear his name.

John Lewis Dyer came to the Colorado territory with the earliest prospectors. In 1861, fearing that he was losing his sight, Dyer put his Minnesota ministry on hold and came West to see the Rocky Mountains. Dyer’s other motive was mining; he was an experienced lead miner from his days in Wisconsin and visions of gold drew him westward.

John Lewis Dyer came to the Colorado territory with the earliest prospectors. In 1861, fearing that he was losing his sight, Dyer put his Minnesota ministry on hold and came West to see the Rocky Mountains. Dyer’s other motive was mining; he was an experienced lead miner from his days in Wisconsin and visions of gold drew him westward.

Raised in the Methodist church, Dyer was cut from the old cloth, bringing a strict religiosity to his preaching. Drinking, gambling and dance violated the teachings of his church. Yet drinking, gambling and dancing were beloved by the miners of the early gold rush. At first, Dyer’s stringency didn’t endear him in the frontier camps and mining towns. Yet Dyer was a “man’s man,” tall, strong, ruggedly handsome, and unafraid to physically remove the “rowdies” from his preaching venues. Miners could relate to him.

Craving a taste of home and the civilization left behind, miners soon filled his uncomfortable log pews, gave him their gold dust, helped him build churches, and joined his congregation. It didn’t hurt that Dyer was also a mail-carrier. Sometimes he would make the men hear a sermon before he released the post.

Dyer was 49 years old when he made his way West, walking next to the wagon train that carried his satchel of earthly goods. The eye condition cleared up, but Dyer never did return to preaching in the mid-west. Mining and the spiritual needs of the men of the Western expansion kept him in Colorado. There was plenty of work for a dedicated man of the cloth, though not much money in it.

To make his rounds of the far-flung mining camps, Dyer quickly learned to ski on “Norwegian snowshoes,” as they were called. The most efficient way to travel across snow in the High Country, Dyer could cover many miles in a day. Dyer commonly started at 2:00 in the morning when the snow was firm. To the song of the howling wolves, he moved mail and ministry from Breckenridge over Hoosier Pass to Buckskin Joe near today’s Alma. After a brief rest, Dyer journeyed atop Mosquito Pass, towering over 13,000’ in elevation, on to Oro City (now Leadville). He might make the return trip the following day.

If a movie were made of Dyer’s life, several stuntmen would be needed to re-enact his incredible adventures. He rode out avalanches, dodged murderer’s bullets, hunkered in Krumholtz at tree-line to survive sudden blizzards, leapt over fallen trees as his homemade raft careened down flood-swollen rivers, fended off flirtatious women, and endured frostbite, snow-blindness, hunger and thirst. Dedication to preaching the Methodist ministry carried him ever onward.

Dyer first came to the Breckenridge area in 1862 as an itinerant preacher on a circuit including the mining camps in French and Georgia Gulches and along the Blue River. Over the decades, Dyer’s ministry brought him to Breckenridge many times. The town was on the economic upswing in 1880 when Dyer donated one of his mining claims in downtown Breckenridge for the site of his church. The Town built a fire hall next door (where the Old County Courthouse is located today). Dyer would “borrow” the fire bell to announce church services on Sunday, bringing volunteer firemen racing to the station for duty. The Town locked Dyer out of the fire house to keep him from further appropriating the bell.

Mining was always part of Dyer’s life in the mountains. He filed many mining claims across Colorado, located valuable veins using a dousing stick, and helped others with mining endeavors. Mining supplemented his meager wages as minister.

Seeking to escape the debauchery of Breckenridge, Dyer founded a settlement near his Warriors Mark Mine in Indiana Gulch south of Breckenridge. He built a cabin there in January 1881 and hoped to surround himself with like-minded Christians in Dyersville. He and his third wife Lucinda moved into their log home in February of that year.

Men plan and God laughs, as the saying goes. Jerry Krigbaum, a colorful saloonkeeper, had a different plan for Dyersville. As if to purposely spite Dyer, he named his saloon the Angels Rest, though it provided no rest for an angelic spirit such as Dyer. Krigbaum’s infamous Christmas and New Year’s parties of 1881 brought drunken debauchery to Dyersville. A Breckenridge newspaper article of the time reported:

“Christmas passed gloriously, all the whisky was exhausted and the substantials soon followed, so [Krigbaum] had to come down among dealers again. New Year’s at Angels Rest will be a grand, free blow-out, everybody welcome…angels of all denominations, character or color, cordially invited.”

John and Lucinda Dyer moved to their ranch in Castle Rock in February following Krigbaum’s legendary holiday parties. He passed away in Denver in 1901 at the age of 89.

Dyer influences Breckenridge still today. The church he built in 1880 moved to a larger lot in 1977 and is home today to a vibrant spiritual community. Services are offered every Sunday at the Father Dyer United Methodist Church.

Dyersville persists as a ghost town accessible on foot, mountain bike or high clearance vehicle. Historians believe they recently found Dyer’s cabin, a pile of rotting logs measuring 17’ square, the dimensions given by Dyer in his autobiography. Today you can see the remains of a livery stable and boarding house. Krigbaum’s Angels Rest lies in ruin a few hundred feet from “downtown” Dyersville. The Warriors Mark Mine is a quarter mile up the rough dirt road.

John Lewis Dyer is also considered a founder of the State of Colorado, and his stained-glass portrait decorates the rotunda of the State Capitol building in Denver.

For more information on Father John Lewis Dyer’s life and work, read his autobiography The Snowshoe Itinerant, or Mark Fiester’s biography, Look for Me in Heaven. To learn more about local Breckenridge history, visit the Breckenridge Heritage Alliance website to browse history articles and blogs, tour a museum, or join a tour.

written by Leigh Girvin