Helen Rich and Belle Turnbull: The Ladies of French Street

March 21, 2022 | Category: Our Collective History

Helen and Belle. Belle and Helen. Always together. Always in the same breath their names are mentioned. Who were the famed Ladies of French Street in Breckenridge? Breckenridge History takes a look at Belle Turnbull and Helen Rich, women of literature who found inspiration in gritty Breckenridge during the height of the Great Depression.

Their rustic cabin on North French Street no longer enjoys the sweeping vistas of the Ten Mile Range that Helen and Belle so cherished. Modern development encroaches on all sides, blocking views of the mountains that inspired their poems and novels. While many writers of the West focused on how man impacted the mountains and the landscape, Helen and Belle captured the people who were molded by the mountains. Their work centered on the ordinary people – illiterate miners, aging prostitutes, impoverished families – who made up the fabric of fading mining communities like Breckenridge. More than the writers who romanticized and glorified the Gold Rush, Helen and Belle were our most authentic chroniclers of historic Breckenridge.

They arrived together in Breckenridge in 1939 after renting a cottage in Frisco for several summers. Retired from professional lives in Colorado Springs, Helen and Belle longed for a quiet life to give all their attention to their writing. Surviving on a small pension from Belle’s years teaching high school English in the Colorado Springs School District wasn’t enough. Helen soon took a position as caseworker with the Summit County Welfare Department, serving as assistant to Susan Badger.

The Great Depression was hard on Breckenridge and even harder on Frisco, where the closing of mines meant the end of electrical service in town. In Breckenridge, the gold dredge boats still tore up the river valleys and employed the last of the hold-out miners. These are the people whom Belle and Helen wrote about.

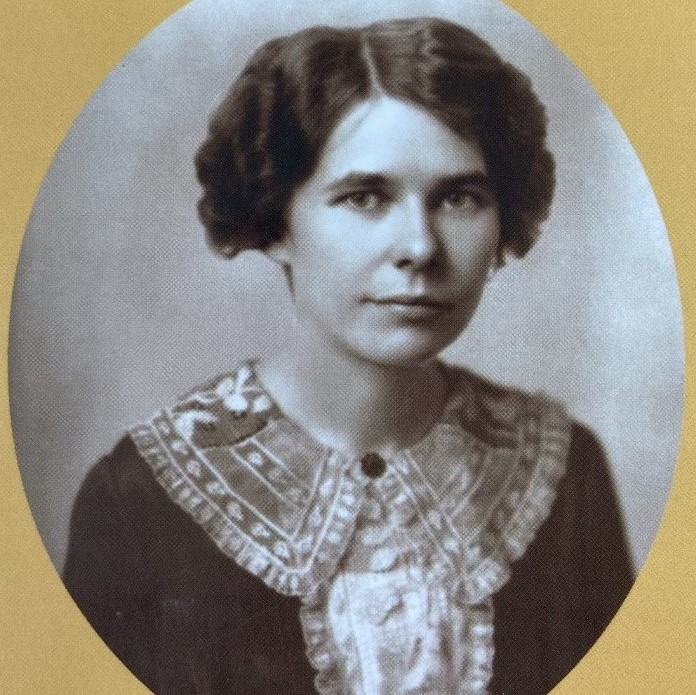

Belle Turnbull, a dozen years older than Helen, was born in 1882 in Hamilton, NY. At the age of eight, her family moved to Colorado Springs where her father took the position of principal of the high school. Immediately she was smitten. “The West was and still is an adventure,” she wrote. After an education at Vassar College, which “certainly didn’t prepare me for life in Breckenridge,” she taught school in New York for a few years. Happy to accept a position as English teacher at the Colorado Springs High School, Belle returned to her beloved West in 1911. Eventually she rose to the head of the English Department.

Helen Rich was raised in Minnesota and Wisconsin in a strict religious household with a dentist father who insisted that she marry or teach. After college, she severed her ties and fled to Paris where she “learned to love life.” In the 1930s, Helen became the society writer for the Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph and it was during this time that she met Belle. Realizing that she hated parties, Helen switched to features, reporting on crime and the sheriff’s office.

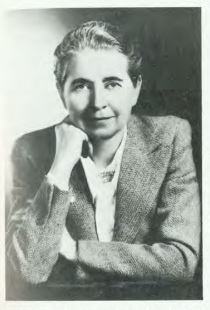

The slow pace of life in Breckenridge allowed the women time to write and the rarefied air inspired them. They were well into their 50s when they began their literary careers. Helen was the better seller of the two writers. Her novel, The Spring Begins, was a best seller in 1947.

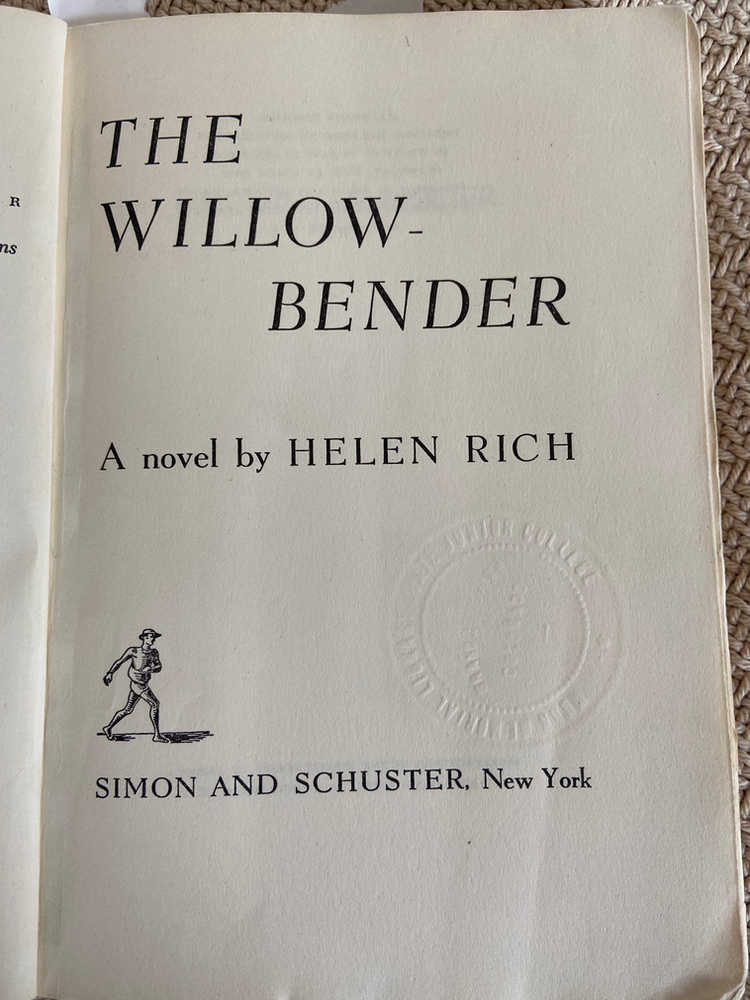

The Willow Bender, her second novel, also received acclaim. Supplementing her income, Helen wrote extensively for local and regional newspapers. Her work can be found in many past issues of the Summit County Journal.

Helen also helped Reverend Mark Fiester with his seminal history Blasted Beloved Breckenridge. But she didn’t attend his Father Dyer Methodist church, professing to be “a heathen.”

Helen also helped Reverend Mark Fiester with his seminal history Blasted Beloved Breckenridge. But she didn’t attend his Father Dyer Methodist church, professing to be “a heathen.”

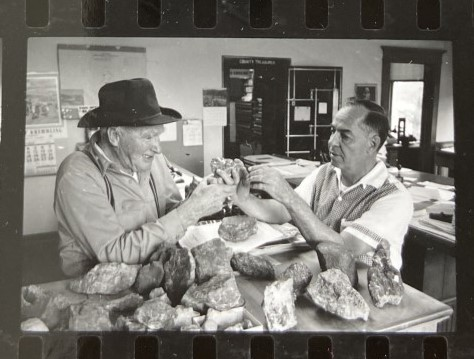

Belle was a poet from her youth, and honed her craft in private until she retired from teaching. While not a financial success in her life, she garnered praise from other poets and, in 1938, received the Harriet Monroe Memorial Prize from Poetry Magazine, earning a $100 award. Goldboat, her most remembered work written in free verse, was published in 1940. It showed her diligent study of gold dredge mining. She would later write a biography of the “dredge boat king” Ben Stanley Revett. In 1953 she published The Far Side of the Hill, highlighting the interdependence of people and place. Her “mastery of the compressed line” was featured in 1957’s The Ten Mile Range, a book of poems that was critically regarded but did not sell well.

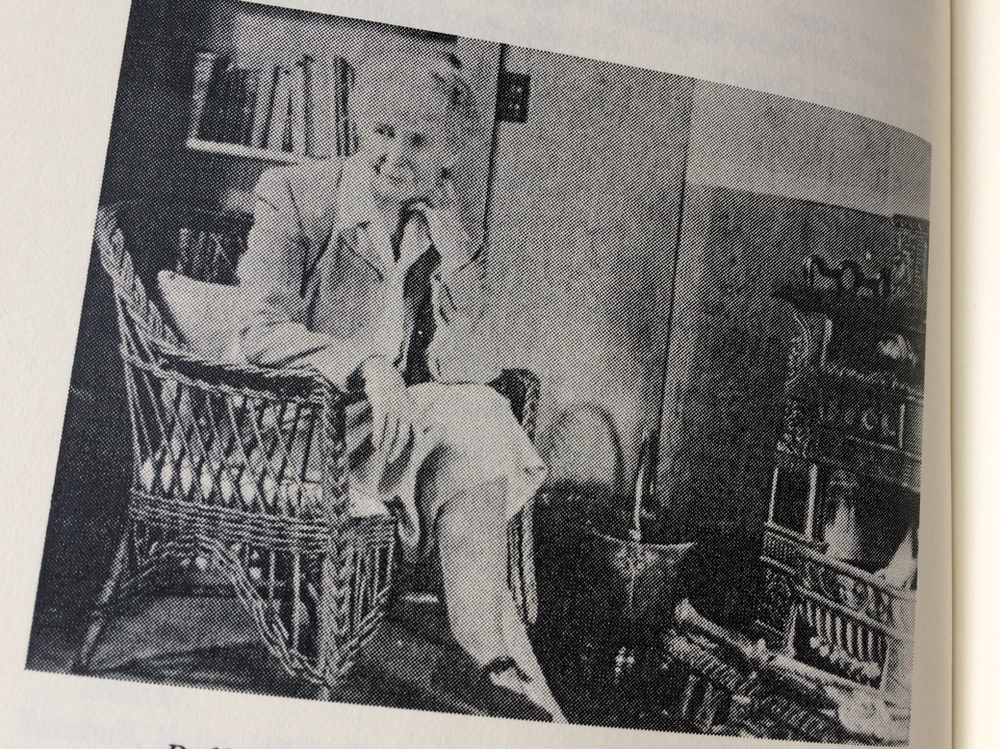

Colorado poet laureate Thomas Hornsby Ferril was a great friend and frequently visited the Ladies of French Street. He valued their drinking whiskey, freshly made bread with homemade jelly, and shared love of fishing. Even more, he enjoyed their conversation, “wry, sparkling, sophisticated, earthy,” he later wrote.

A visit with Helen and Belle was a near requirement for famed literati touring through Colorado. May Sarton — poet, feminist, out lesbian and founder of the May Sarton Poetry Prize– was enchanted with Belle’s poetry and valued Helen’s friendship. Alex Warner, editor of the Colorado Quarterly, escorted May to Breckenridge along with his novelist wife, Marie. Poet Carl Sandberg took a trip to Salida with Helen and Belle. Helen often mentioned visits with Muriel Sibell Wolle, artist and author of Stampede to Timberline.

Ferril once brought Pulitzer-prize winning historian Bernard DeVoto to visit the Ladies of French Street. A family friend, who accompanied the men on the trip, remembered the lively conversation among the great writers where DeVoto found “more than a sympathetic ear” in Helen. The ladies’ whiskey and homemade bread enlivened the talk “during an increasingly animated give-and-take.”

Helen, the more gregarious of the two, was rarely condemning in her observations and conversation. She saved her condemnation for the men of the Denver Water Board. They wanted west-slope water and they came to Breckenridge to let the locals know that they did not need to ask for it, only to take. “They were rude men,” Helen observed. They were not welcome at the house on French Street.

For Breckenridge longtimers, the house on French Street was welcoming. At Helen’s memorial gathering around her gravesite in Valley Brook Cemetery, one miner broke the awkward silence, warmly remembering the lively poker parties the ladies hosted in their bungalow. Wrote one observer: “Both Helen and Belle had a salty, earthy, sense of humor that endeared them to their Breckenridge neighbors as well as to the literati who sampled Helen’s boilermakers.”

The ladies’ relationship to their salt-of-the-earth neighbors wasn’t a one-way street, taking their jargon and stories for their own literary creations. Miner Curly Mackie, an inspiration for a character in one of Helen’s books, was illiterate. In cooperation, Helen helped him with his correspondence.

Helen and Belle saw the transition from mining town to ski town. Helen “dreaded the ski boom” and wanted Breckenridge to stay the way it was. Yet the women were still welcoming to newcomers. Best-selling author Sandra Dallas was a young bride in Breckenridge in 1963, coming to town with her husband who was the first public relations manager for the new Breckenridge Ski Area. She soon befriended Helen and Belle, but mostly Helen as Belle’s memory was fading by then. She remembered asking Helen about Belle: “Belle forgets,” Helen replied, “and it bothers her that she forgets. But then, she forgets she forgets.”

Helen Rich encouraged Sandra Dallas to write about Breckenridge: “you have the gift.” She prodded Sandra: “the stuff out of which such books are made has to seep into a person.” Indeed, she was right. Several of Dallas’ popular books of historical fiction are based on Breckenridge, including Whiter Than Snow and Prayers for Sale.

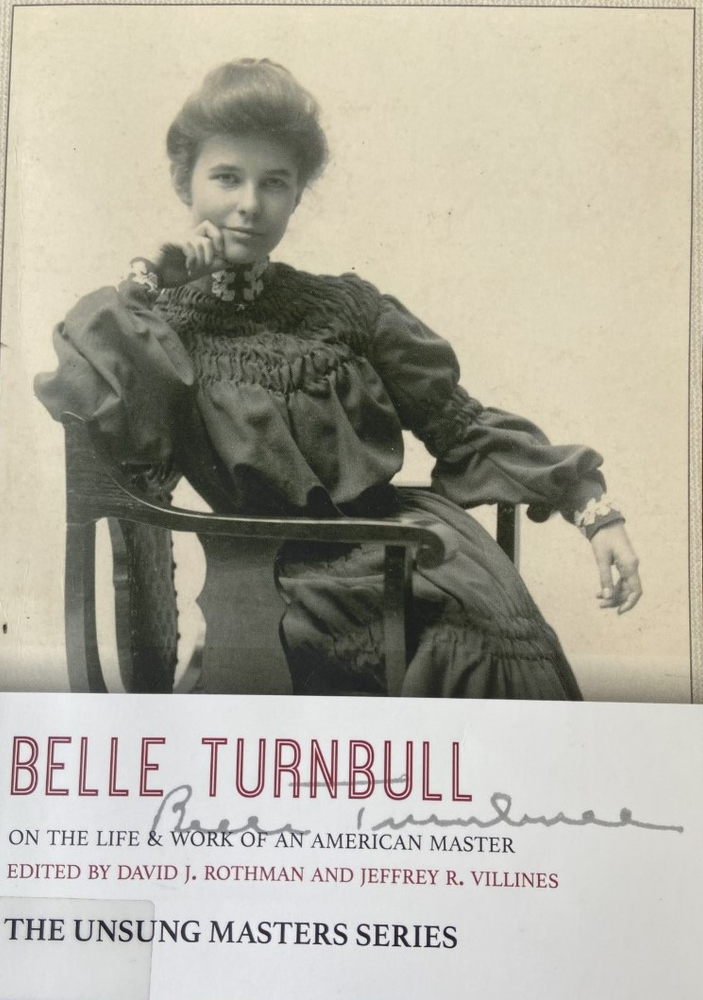

Belle Turnbull died in 1970 and Helen Rich followed her in death a year later. While Helen was the better-known writer in their day, Belle’s poetry has recently been rediscovered. The Unsung Masters Series featured Belle in a 2017 publication with reprints of many poems and critical commentary from modern writers and poets. Extolled one: “She is a poet of Colorado, but also a substantial American poet, perhaps a great one.”

Breckenridge was the better for having Helen Rich and Belle Turnbull as part of it. They held a mirror to the community that reflected authenticity, quirkiness and the resilience of a bristlecone pine on a high mountain ridge. In closing, we share this poem by Belle Turnbull about mountain women from the Mr. Probus (a miner) series:

Mountain Woman

God love these mountain women anyway,

Said Mr. Probus. Not to say they’re fair

Or sleek with oils, for woodsmoke in the hair

And sagebrush on the fingers every day

Are toughening perfumes, and the sunstreams flay

Too dainty flesh. But what remains is rare,

Like mountain honey to a mountain bear;

He finds his relish in a rough bouquet.

Days when their wash is drying, off they’ll go

And fish the beaver ponds. Hell or high water,

They wade the slues in sunburnt calico

Playing their trout like some old sea king’s daughter.

Hell and high water women…Steady now!

Not all of them, he said. One, anyhow.

For a more thorough analysis of the lives and work of Helen Rich and Belle Turnbull, see this article from Colorado Magazine published in 1979. Summit County Library has a copy of the Unsung Masters Series: Belle Turnbull, On the Life and Work of an American Master.

To learn more about Breckenridge history, visit a museum, take a tour, or read blog articles from Breckenridge History.