Louis Ford: Part 3 – The Final Years

April 26, 2022 | Category: Our Collective History

Louis Ford celebrated his 31st birthday in the Missouri State Penitentiary. By the time he was 40 years old, Louis Ford spent half of his adult life behind bars. For the son of Barney L. Ford, a man whose shining example of rising from adversity should have been a beacon for his son, Louis’ life as a criminal was a heartbreaking fall from grace. In this third of three parts, Breckenridge History examines the final years of Louis N. Ford.

The Breckenridge Bulletin remarked on this fall from grace when it wrote in June 1902, “Money certainly seems to have been the root of considerable evil in the Ford family.”

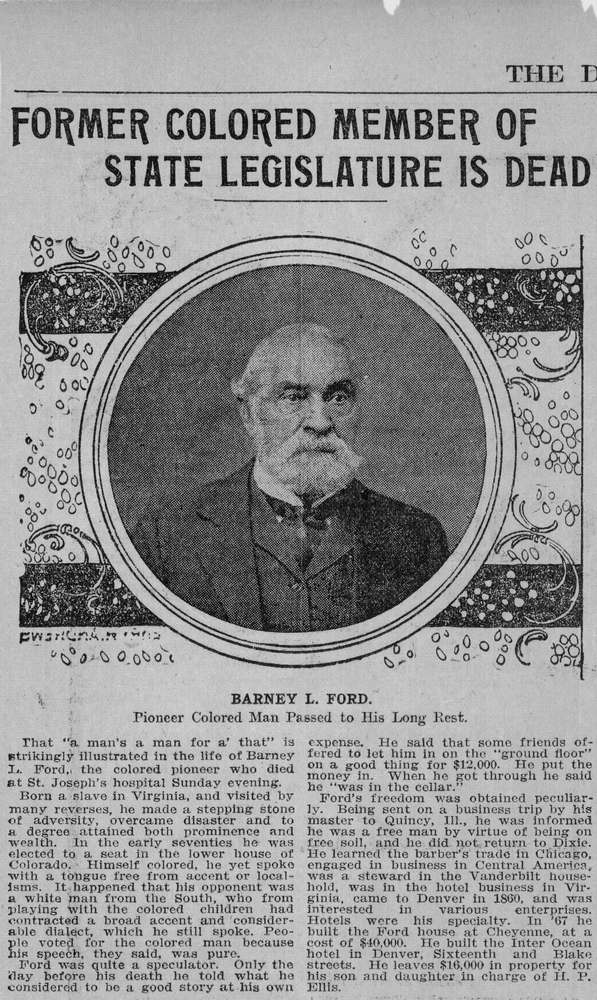

What was happening in June 1902 that would cause the Breckenridge newspapers to comment on “considerable evil in the Ford family”? In June 1902, there was no way the local Summit County newspapers could know that Barney Ford would die only a few months later. Upon Ford’s death in December 1902, the Summit County Journal published an obituary mentioning his many friends in Breckenridge. Another obituary talked about what a fine man he was. The evil clearly wasn’t Barney Ford himself.

What salaciousness was going on that would spur the Bulletin to make such a quip? Son Louis was on his way to prison yet again.

Louis Ford was brought up in the Wild West towns of Denver and Cheyenne where lawlessness prevailed. Common street scenes allowed him to witness shootings, theft, prostitution, drinking, gambling and the wild ways on the frontier. To an impressionable youth, vice was normalized.

And Louis Ford fell into vice and crime from a young age. At 17 he was accused of stealing cash from a guest at his father’s Inter-Ocean Hotel in Cheyenne. Ten dollars doesn’t seem like a lot of money to us, but in 1878 it was equivalent to about $275 today.

Louis escaped prosecution that time, but his criminal ways would catch up with him. In his twenties, he was imprisoned in Colorado for burglarizing a jewelry store in Salida. Shortly after his release from prison, he found himself seriously injured in a fight with a fellow gambler after being accused of cheating. And not long after that, a charge of robbery in the first degree would land him in the Missouri State Penitentiary to serve a ten-year sentence. Learn more about Louis’ earlier years in Part 1 and Part 2.

Louis Ford was afforded every opportunity to succeed in life. His parents made education a priority. His personal letters show a command of spelling, grammar and penmanship from years in school. Barney Ford hired Louis to work in his hotels and restaurants, providing valuable experience. Yet Louis chose a different path, looking for excitement and easy money in gambling and taking from others.

In 1899, Louis was a free man again. His mother had died in May 1898 and he expected a cut of her estate. He made his way to St. Louis, Missouri, for reasons unknown today.

There he took a place in Clara Isom’s boarding house under the promise that he would pay her $25 a month for room, board and washing as soon as he got his money from his parents’ estate. He even showed her papers that he would be receiving money.

Clara was wise to be skeptical. She hired attorney Eli Taylor to investigate Louis’ Denver properties. Apparently satisfied, she agreed to the arrangement.

But a month stretched to months and then to years without payment. Not long after Louis arrived at Clara’s he fell from a wagon, requiring treatment from a doctor. Clara paid the bill, furthering Louis’ indebtedness to her.

Upon meeting with a friend one day, the friend asked how Louis paid for the sharp set of new clothes he was wearing. Clara covered it, Louis replied, and he’d pay her back, every cent, as soon as he got his parents’ estate.

In early June 1902, Louis Ford was arrested in St. Louis for attempted burglary. On June 5, Clara hired an attorney, at her expense, to help Louis.

Louis must have been the talk of the town, Denver and Breckenridge that is. The Breckenridge Bulletin’s observation was printed on June 7, 1902. The “evil” wasn’t just Louis’ latest arrest, however. In the summer of 1902, Barney Ford was writing his will, protecting his assets and estate from a son who clearly had little regard for the law or property of others.

Barney Ford placed the Denver commercial property at 1313 15th Street, which he had received from wife Julia’s estate, in trust for his two surviving adult children, Sarah Wormley and Louis Ford.

In early July 1902, Louis was sentenced to two years in the Missouri State Penitentiary. While he was there, six months later, Barney Ford died in Denver. When Mr. Ford last saw his son is unknown, though it could have been years.

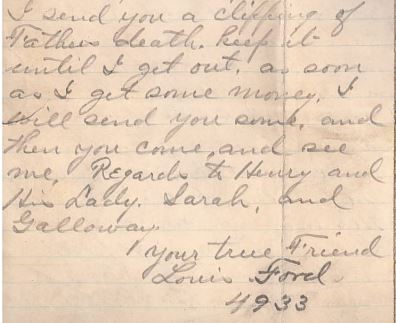

Two prison terms teach a man at least one thing: how to navigate life in prison. By the time of his third sentence, Louis was a prison pro. Louis Ford’s letters to Clara Isom talk about mail service, meeting with the warden, working in the prison shop, and gambling. Lots of gambling.

Louis also requested Clara to send him food. Copious amounts of food. There is no way one man could keep fresh and eat pork tenderloin, pig tails, chicken, two dozen eggs, a dozen lemons, a half-dozen oranges, a big cake and a large bag of nuts, all from one express delivery. Most likely he was selling or trading the food to his fellow inmates.

Throughout his prison term, Louis never gave up hope for a better life for himself on the outside. And that life was based on receiving a considerable estate from his father, Barney L. Ford. He promised Clara that he would set her up in a “first class” house. He planned for the day the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair would bring throngs of tourists to the city.

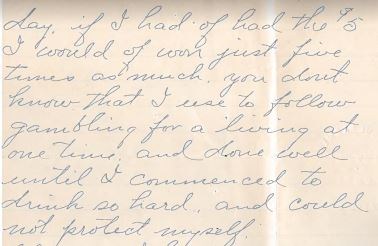

Perhaps he knew that the debt he owed Clara kept her on the hook. He felt that he had suasion over her, even from 113 hundred miles away in prison. In one letter, he admonished her for being late sending him money because it meant he had that much less to gamble with. “I would of (sic) won five times as much,” he lamented.

When his father died, Louis’ dreams and schemes amplified. He wrote of investing in real estate, opening a saloon with “fine furnished rooms,” and starting a factory to manufacture a new invention created by one of his fellow inmates, a combined mop and wringer.

Louis expected to inherit thousands of dollars. He sent to Clara a clip of an obituary of “Father’s death,” likely the same one on display in the Barney Ford Museum. The obituary stated that Ford “leaves $16,000 worth of property for his son and daughter in charge of H.P. Ellis,” worth about a half a million dollars today.

Louis knew exactly when he would be released from prison under the three-fourths law. He encouraged Clara to save up money so he could purchase a train ticket to Denver, a round trip ticket. “…Do this for me just as I tell you to do it,” he ordered.

On January 8, 1904, Louis Ford was released from the Missouri State Prison in Jefferson City. He spent just one day with Clara in St. Louis, then departed for Denver on January 9. He sent her a postcard from Denver on January 11. That was the last Clara heard of him.

Among the items that Barney Ford bequeathed his son was a trunk of personal effects including two suits of clothes, an overcoat, shaving mug, blanket and pillow. Louis signed a receipt for them on January 20.

Ford’s will also left his gold-headed cane, diamond stud, and watch to Louis, attributes which appear in Ford’s stained glass portrait at the Colorado State Capitol. But attorney Ellis claimed no knowledge of their whereabouts and Louis does not mention the items in his own will. The final disposition of Barney Ford’s most valued personal possessions remains a mystery.

On March 5, 1904, Louis and Sarah sold the property at 1313 15th Street. But all was not well with the newly freed and well-to-do Louis. He needed surgery to amputate his leg, a surgery “from which he did not expect to survive.”

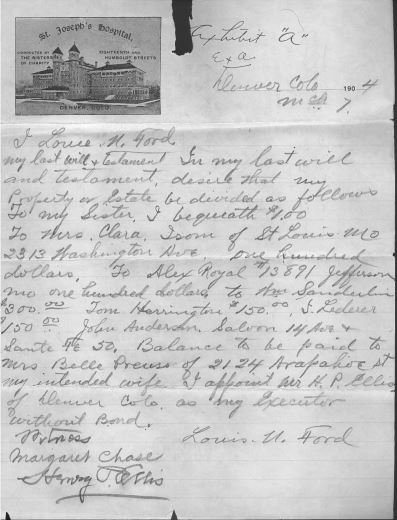

Louis made out his will on stationery from St. Joseph’s Hospital on March 7, the day scheduled for his amputation. In it he left money to a long list of friends and acquaintances. But he stiffed his sister Sarah, leaving her only $1, despite borrowing about $100 from her over the years. The trend of his legacies was to pay back people to whom he owed money. He left $50 to a saloon keeper, $300 to attorneys, and $100 to Clara Isom, though he owed her considerably more for her generous support over the years. One curious legatee was Alex Royal, a fellow inmate who was serving fifteen years for murder. Louis willed him $100, perhaps for gambling debts. One hundred dollars in 1904 is worth about $3,400 today.

In a romantic twist, Louis left the residue of his estate to a Mrs. Belle Pruess, his “intended fiancé.” In one appeal of Louis Ford’s estate, we learn that Belle Pruess is Isabella Sanderlin Pruess, the daughter of long time Barney Ford friend and fellow barber, Ed Sanderlin. Belle died a few weeks after Louis.

The reason for Louis’ amputation is unknown. Clara expressed concern about his health. In some of his letters to her, Louis responded to that inquiry, stating he was fine and “I hope you are as well as I feel.” Louis died from complications of the surgery on March 10, 1904, at age 43.

The execution of Louis Ford’s estate was long and convoluted, taking years to make its way through the Denver courts. Because claimants perceived the estate to be sizeable, a lot of people wanted a piece of Barney Ford’s wealth. Attorney Henry P. Ellis – who executed the wills for Julia, Barney and Louis – avidly defended the estate against claims.

In the end, the value of Louis’ estate was considerably less than he originally expected. The Denver Post reported that Louis spent a large sum “carousing.” Lawyers and other expenses depleted the fund. Most people were eventually paid a portion of what they were owed by Louis, and the court awarded the residual to Clara Isom, whom they identified as Louis’ common-law wife. Clara’s receipt of the funds, about $750 less attorney fees, remains unknown. It appears that her lawyers tried to swindle her too.

Despite his sweet-talk cons and criminal behavior, Louis seemed to have a good heart. He tried to pay back the people he owed and make good on his promises. People stood by him and helped him, even in his darkest hours. He is buried next to his parents in Riverside Cemetery in Denver.

To learn more about Breckenridge History, click on the website, take a tour, visit a museum, and check out our blog articles.

Written by Leigh Girvin