Myth-busting: The True Story of Barney Ford

February 22, 2022 | Category: Our Collective History

The story of Mr. Barney L. Ford changed completely in spring 2021 when the Breckenridge Heritage Alliance (BHA) received a new primary source document in Mr. Ford’s own words. Now armed with accurate information, the BHA understood how he achieved his freedom, when he adopted the name “Ford,” and when he was manumitted.

The document opened pathways of understanding about Barney Ford that were not available when his fictionalized biographies were published in the mid-20th century. In this article, the Breckenridge Heritage Alliance shares new information that puts to rest many of the myths and tells the true story of Mr. Barney Ford.

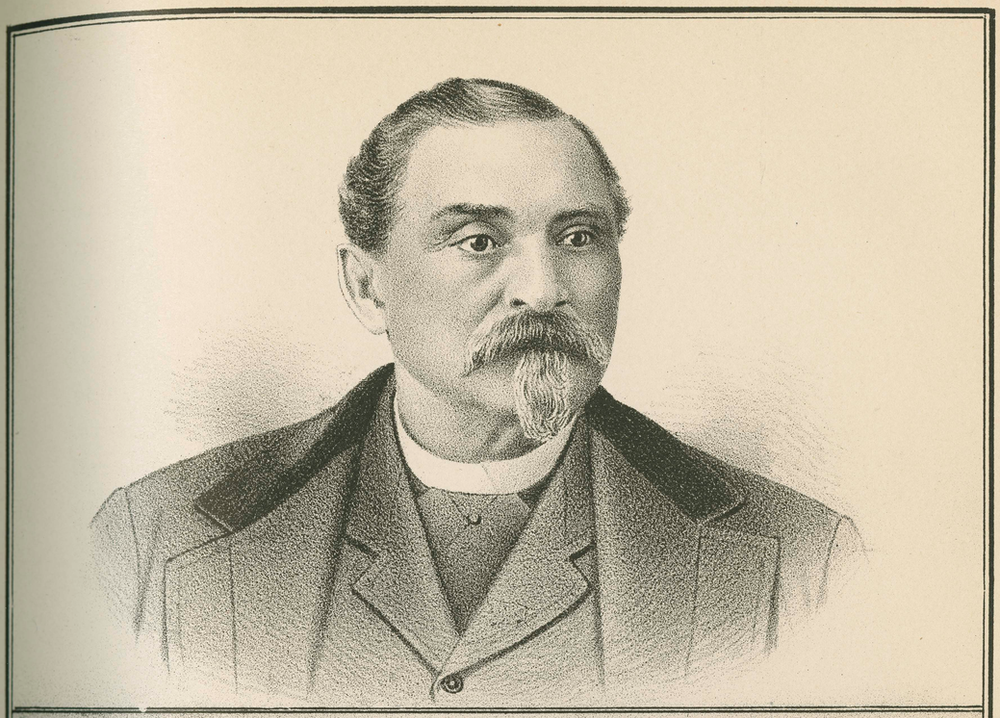

The best source of primary information about B.L. Ford is the seminal History of the State of Colorado, told in four volumes by General Frank Hall written over the final decades of the 19th century. Hall’s Biography section includes two and a half columns on Ford’s life, one of the longest profiles in the book, and longer than many other prominent citizens of the time. Hall also wrote one of Ford’s obituaries, sharing additional information not included in the original biography and revealing personal observations that reveal their friendly relationship. Census data, advertisements and newspaper reports fill in additional details about Barney L. Ford, his businesses and his family.

Yet there are significant gaps in Ford’s life that are likely unknowable. Enslaved people were property, not persons, and certainly not citizens. Records of the enslaved are virtually non-existent. And Ford didn’t appear to talk much about that part of his life. As Hall said relating Ford’s disinterested narrative of his period of enslavement: “the adventures that he passed through were mere incidents that might have happened to any person.”

When Forbes Parkhill wrote the first biography of Barney L. Ford in 1963, Mr. Barney Ford: A Portrait in Bistre (bistre is a pigmented wash used in illustration), Parkhill made up a story where he lacked information. Even his publisher, Johnson Books, acknowledged that fiction. Doris Sanders, director of the Book Department, wrote to Dr. W. Stanton Wormley in 1975, saying the biography was “fictional in approach, but factual in terms of dates, etc.” Yet in many cases, not even the dates in Parkhill’s book are correct. (Wormley was seeking information about his step-mother, Sarah Ford Wormley, middle child of B.L. Ford.)

Unfortunately for history, Parkhill’s account of Ford’s life has been taken as gospel truth ever since.

While there may be fallacies carried through the historic narrative of Ford’s life, there is one consistent truth enthusiastically shared from all sources: Barney L. Ford was a fine human being. From Hall’s biography to his many obituaries, Ford’s chroniclers give him high praise. Breckenridge’s Summit County Journal quoted from The Society of Colorado Pioneers, saying “He was a man of the highest moral sense… No arrogance ever accompanied his well-earned gains, nor did poverty lessen his renewed energy to recuperate his broken fortunes.” Hall’s obituary concluded: “Barney Ford was always and under all circumstances a gentleman in the cleanest sense of the word…. Quiet, modest and very intelligent, a close observer of current events, he was an interesting talker when you could get him started.”

This is the true story of Barney L. Ford

A baby named Barney was born to an enslaved African-American woman in Stafford Courthouse, Virginia in January 1822. This child was raised in South Carolina, and in his youth learned to read and write, “entirely self-taught” according to Hall.

In his teens he was droving hogs and mules between Kentucky and Columbus, Georgia, then he worked on a cotton boat on the Apalachicola River. It is possible that Ford was exposed to gold mining as he moved through northern Georgia during that area’s gold rush of the 1830s.

In spring 1844, at age 22, he was purchased by Nathanial Garland Woods, of Kentucky stock, but residing in St. Louis, Missouri. During part of his time with Woods, Barney worked on river boats on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. In October 1848, Wood brought Barney with him to the Illinois city of Quincy, a sizeable river town on the Mississippi River, and an important stop on the Underground Railroad. For reference, Quincy is just 16 river miles from Hannibal, Missouri, site of fictional Big Jim, Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer’s many adventures.

In 1848, Illinois was a free state and Barney knew it. The law at the time: If a man brings his slaves to the state and stays ten days or longer, then those slaves are free. The BHA feels it is safe to assume that Woods had Barney with him in Quincy on business and that they stayed at least ten days.

Barney left Woods in Quincy, but not before leaving him a letter, a long letter. In it, he outlined his grievances and why he deserved his freedom. He signed the letter, “Your humble servant, B.L. Ford.” Barney was 26 years old when he achieved his freedom. Read the full letter at this link.

With the help of the Underground Railroad, Barney made his way to Chicago, about 300 miles distant. There he met Julia Lyons, sister-in-law of the man running the Chicago Underground Railroad, Henry O. Wagoner. Julia and Barney were married in 1849.

Ford’s letter to his enslaver was published two years later in the abolitionist Chicago Western Citizen newspaper. Before Woods died in 1850, he wrote “I will my slave Barney now in Chicago shall be emancipated and his papers sent to him by my executors.” Perhaps those papers included Ford’s letter(s) as it was customary in that era to return letters to the sender on the death of the recipient. By October 1850, Barney Ford was no longer a fugitive, but a free man.

Ford’s 20th century biographers did not have the Quincy letter. Instead, they made up stories of Ford’s escape, based on the historic record and how other enslaved people found their freedom in Quincy, Illinois. Parkhill said that a cohort tossed a bushel of rice overboard, shouting “Man Overboard,” giving Ford the opportunity to flee down the gangway. In another biography, Ford escaped the riverboat by dressing as a woman with the help of the on-board actor. Pure fiction both.

Parkhill also perpetuated the myth that Barney L. Ford took his name from a locomotive seen in Chicago, the Lancelot Ford. Such an engine never existed in Chicago in Barney’s time. And now, with the Quincy letter, we know that Barney had adopted the last name “Ford” by October 1848. That Woods does not acknowledge the name Ford in his will may indicate that Barney chose “Ford” at the time he took his freedom. The source of the name “Ford” and specifically when Barney adopted it are unknown.

The middle name “Lancelot” is also a fiction. In no record do we see the name “Lancelot.” Ford also never used the name “Barney” except in a few legal documents. He was almost always B.L. Ford. During the 19th century, as population increased, many men took an initial for their middle name.

Almost nothing is known of Ford’s mother, though Parkhill named her Phoebe and wrote that she drowned when Barney was a teen, apparently searching for help from the Underground Railroad. Thanks to modern technology that allows for on-line search of digitized historical newspapers, we know that Barney visited his ailing mother in South Carolina in 1870. Sadly, no city or name is identified, leaving more questions to pursue.

Once manumitted, Ford’s gold fever drove him to seek his riches in the California gold fields. In 1851 he departed for the west, but made it only as far as Nicaragua, traveling by boat from the East Coast. This time of Ford’s life is well documented in Hall’s biography, but what about Julia? Parkhill places her in Nicaragua with Ford, but the BHA believes this is highly unlikely. Learn more about Julia and the reasons why she probably stayed in Chicago in this article.

Gold fever brought B. L. Ford to the Pikes Peak region with the early wave of prospectors. He was in Denver by spring of 1860, and in the Breckenridge area in 1861. A local story tells that Ford was chased off his Breckenridge claims by the sheriff, but this is unsubstantiated. Ford was in the Central City area filing claims in 1860, and in Lincoln City east of Breckenridge with a boarding house in 1861. There were men of color mining in 1860 in French Gulch between Breckenridge and Lincoln, but these men were not Barney Ford.

Another local myth that persisted about B.L. Ford through the years is that he returned to Breckenridge in 1879, not just to open a restaurant, but to find the gold he had buried on his old claim eighteen years before. There is no way to verify this old rumor and therefore, the BHA doesn’t perpetuate it.

Parkhill identifies Ford’s first restaurant as The People’s Restaurant, opened in 1863 after the disastrous Denver fire in April. Ford advertised a lot, and historic newspapers show that his first restaurant, THE People’s Restaurant, advertised oysters as early as November 1861.

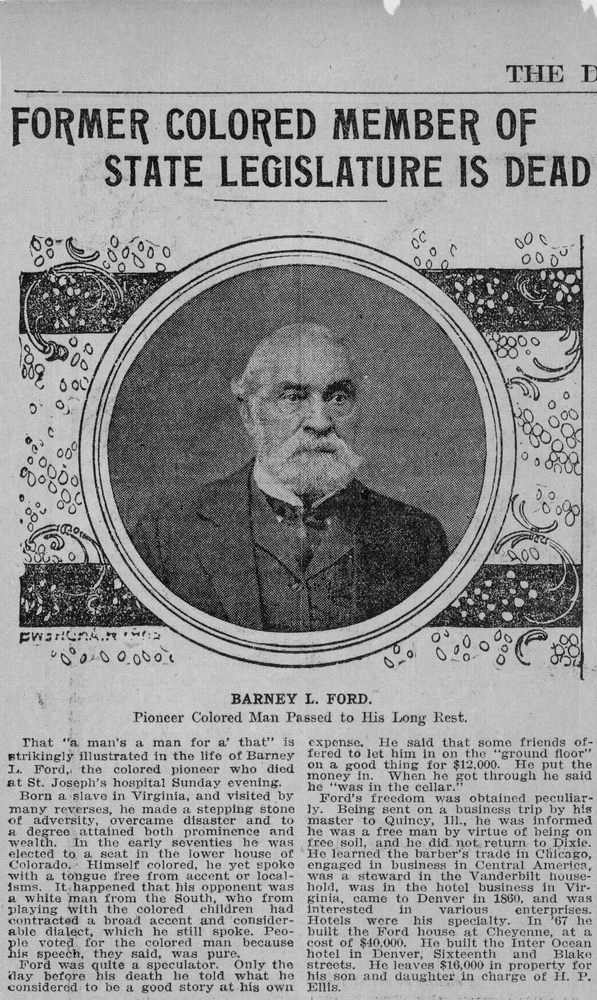

When Barney L. Ford died in December 1902, just weeks shy of his 81st birthday, one obituary said that he had been a state legislator. Ford ran for the Territorial legislature in 1873, but was not elected. It is a tribute to his prominence as a citizen at the time of his death that the writer thought he was elected. This same obituary stated that Ford was sent to Quincy on business by his enslaver, and that allowed him the opportunity to escape. With the Quincy letter, we know that Ford accompanied Woods to that city.

New information continues to surface about Barney L. Ford. The Breckenridge Heritage Alliance is dedicated to sharing the true story of Mr. Barney Ford. For more information about Ford and his legacy, visit the Barney Ford House Museum.

To learn more about Breckenridge history, visit a museum, join a guided tour or hike, or read our history articles and blogs.

Written by Leigh Girvin