The journey home: An 1862 ambrotype returns to Breckenridge

July 31, 2024 | Category: Making History Happen

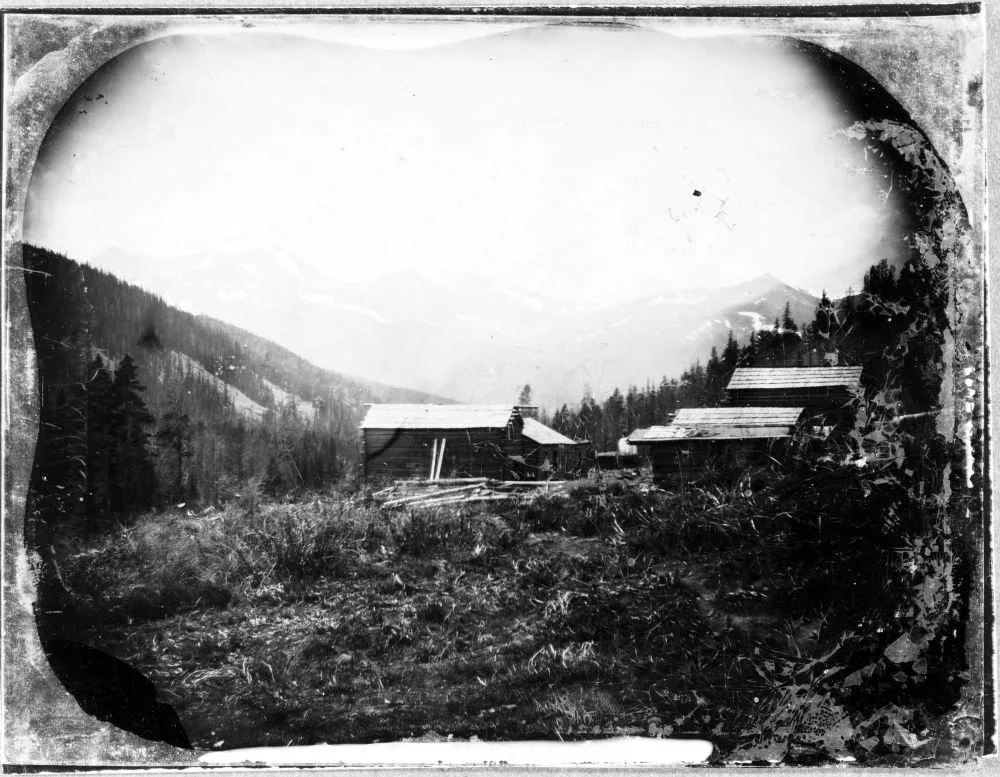

This 1862 ambrotype shows the French Gulch mining camp in Breckenridge, Colorado.

Our knowledge of history is ever evolving. We learn new stories, correct old stories, and get to present a fuller picture of the past thanks to new research, new technology, and new connections. At Breckenridge History, a new connection between our archivist Kris Ann Knish with the Montana Historical Society has helped us to uncover a piece of our history.

What we knew

The Montana State Historical Society had what they believed to be a tintype photo of a mining camp called “French Gulch.” It was accessioned into their collections in 1969 after being donated by Glanville Smith. Smith is the grandson of a man named John G. Gill, who immigrated to the United States from England as a child, according to a letter from Smith. Gill would go on to live in Kansas, Michigan, and Montana before his passing in Oklahoma. The photo, which Smith inherited from Gill, read “French Gulch, Aug. 23, 1862.” This led Smith to the Montana Historical Society, as he knew his grandfather had spent time in the area. The Montana Historical Society believed this photo was one of the earliest in their collections, if not the earliest.

What we know

Over the next few years, they learned John Mix Stanley had taken photos of members of the Blackfoot tribe in the 1850s and that the French Gulch photo was not a tintype, but actually an ambrotype, according to a blog from the historical society. Ambrotypes were popular in the 1860s with photographers out in the field because they could be developed so quickly.

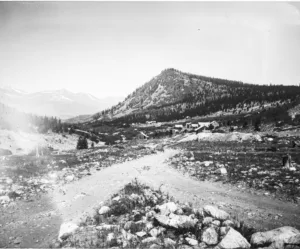

This circa 1890s to 1900s photo by Mary Marks shows the same mining camp as the 1862 ambrotype.

Enter Montana Historical Society Photo Archives Manager Jeff Malcomson. Malcomson took up the charge of learning more about this historical photo. He ventured out to two Montana French Gulch locations and determined that neither matched the location of the photo. Not to be deterred, Malcomson continued his research by examining surrounding states to try to find the correct location. Malcomson’s personal history as a graduate student at Colorado State University led him to start looking in Colorado. He soon discovered French Gulch right here in Breckenridge and managed to match up the peaks in the ambrotype with our very own Ten Mile Range. From there, Malcomson began to correspond with Knish.

Archives have a very focused area of concentration, and while we love a wide range of historic subjects, our archives have to include focused collections. With this knowledge in mind, Malcomson began the process of deaccessioning and transferring the ambrotype to Knish and the Breckenridge History Archives. None of us take donations lightly and this process can be lengthy because we all want to make sure our donations, collections, and history are well taken care of and in the appropriate place. Even more questions sprung up: If the object was to be moved, how do you move it? Ambrotypes are made of glass and sensitive to exterior conditions. They need to be treated with care and simply popping one in the mailbox didn’t seem like an appropriate action. Beyond that, there are governing boards, archival policies, and a number of other factors to consider before the object can officially be transferred.

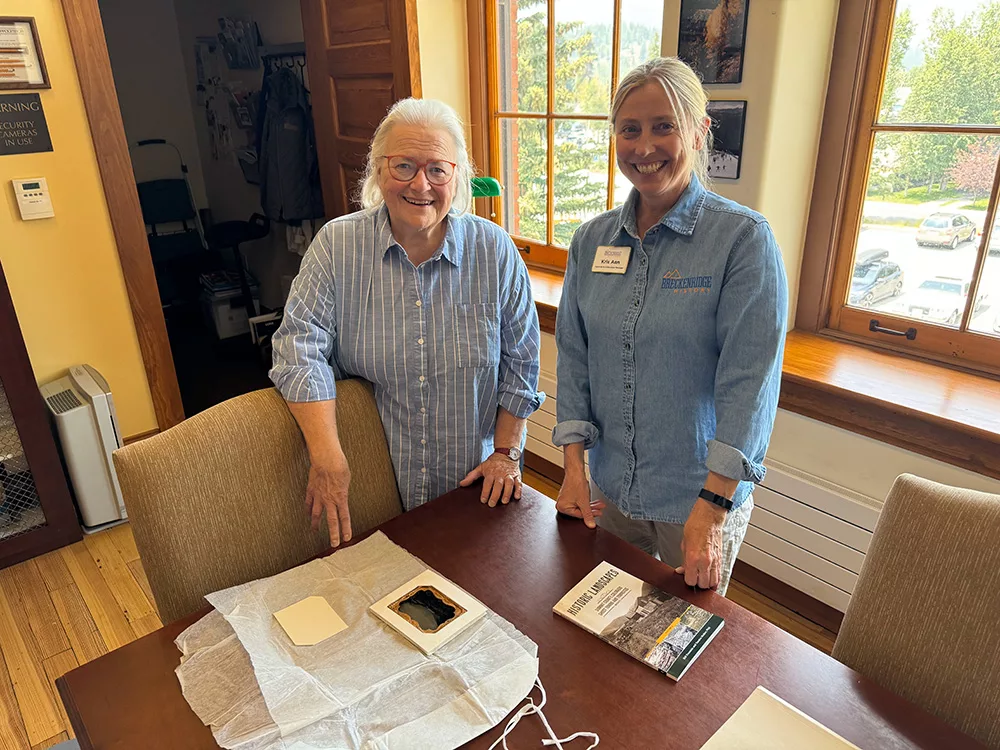

Earlier this month, two trusted associates and former members of staff at the Montana Historical Society, Kirby Lambert and Becca Kohl, made the journey to Breckenridge. They hand delivered the ambrotype to Knish on July 23. It will now be processed into the Breckenridge History Archives and digital copies will be made available to public researchers. The original will be kept in cool, light-sensitive storage so that it can be preserved for generations to come.

Kirby Lambert and Becca Kohl stand behind a table in the Breckenridge History Archives. On the table sits an 1862 ambrotype.

We are very grateful for the efforts of Malcomson and the Montana Historical Society to ensure this piece of our history made its way back home. Now, our research will continue so that we can present an even more complete story surrounding this remarkable photograph.

Becca Kohl and Kris Ann Knish stand next to a table in the Breckenridge History Archives. On the table sits the 1862 ambrotype.

What we still don’t know

Was John G. Gill a miner in French Gulch Colorado? Was he the photographer? If not, how did he end up with the ambrotype? Are there other ambrotypes from the time period and area that we have yet to discover? If Gill wasn’t the photographer, who was? We know there was a photography studio in Parkville, would that photographer have ventured up to take photos on location? The wonderful – and occasionally infuriating – thing about history, is everything you learn leads to more questions. This mystery has been unraveling for 162 years, and we are very proud to have this many answers and to have this incredible piece of history back home. Now we’ll see what we learn and what new questions will come about in the coming years.