Women of Willpower: Breckenridge Pioneers

March 29, 2022 | Category: Our Collective History

Pioneering women of Breckenridge’s early days, who survived and thrived in the unforgiving mountain environment of Colorado’s mining communities, shaped Breckenridge history. While many women came and went from Breckenridge, few exhibited the willpower to stay the course and create community from wilderness. And many women barely hung on in the rough mining town. Meet three women of willpower and a fourth fragile flower, all examples of the women who made Breckenridge.

Hearty community builders Agnes Ralston Silverthorn, Catherine Sisler Nolan, and Minnie Roby had at least one thing in common: resilience. Their ability to adapt to difficult circumstances, improvise solutions, and rise above their standing as Victorian women, set them apart from their eastern counterparts. Western society granted women greater opportunity than was available “back East,” and they took advantage of it.

In contrast, Anna Sadler Hamilton spent her years in Breckenridge worrying about family back home, lamenting the harsh conditions, and distancing herself from other women in town. The diaries of her time in Breckenridge paint a life of unhappiness.

Women in the Victorian period are rarely identified by their own name. Once married, newspapers referred to them by their husband’s name, as in Mrs. Marshall Silverthorn. Because women were inextricably linked to their men, our stories of these stalwart women start with their husbands.

Breckenridge’s first family, the Silverthorns, lived in town at a time before newspapers, yet their lives were well chronicled by the many traveling writers who passed through in the 1860s and 1870s. In addition to those tales, granddaughter Agnes Finding Miner captured much of the family’s history in two manuscripts available in the breckhistoryarchives.

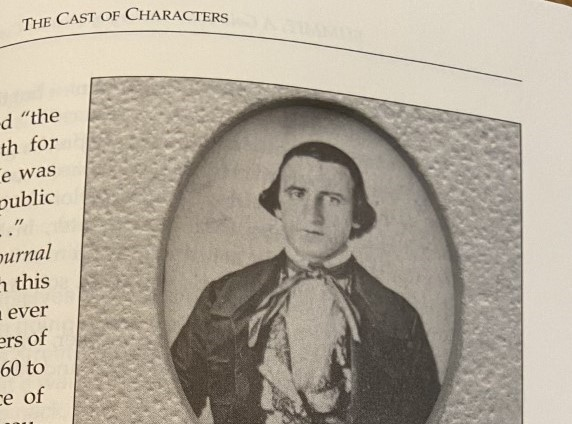

Marshall Silverthorn arrived in Denver City in 1859 with the first wave of gold prospectors to regain his health. Taken with the climate and opportunity in the Pikes Peak gold region, he returned to Pennsylvania the next year to gather his wife and family for a permanent move.

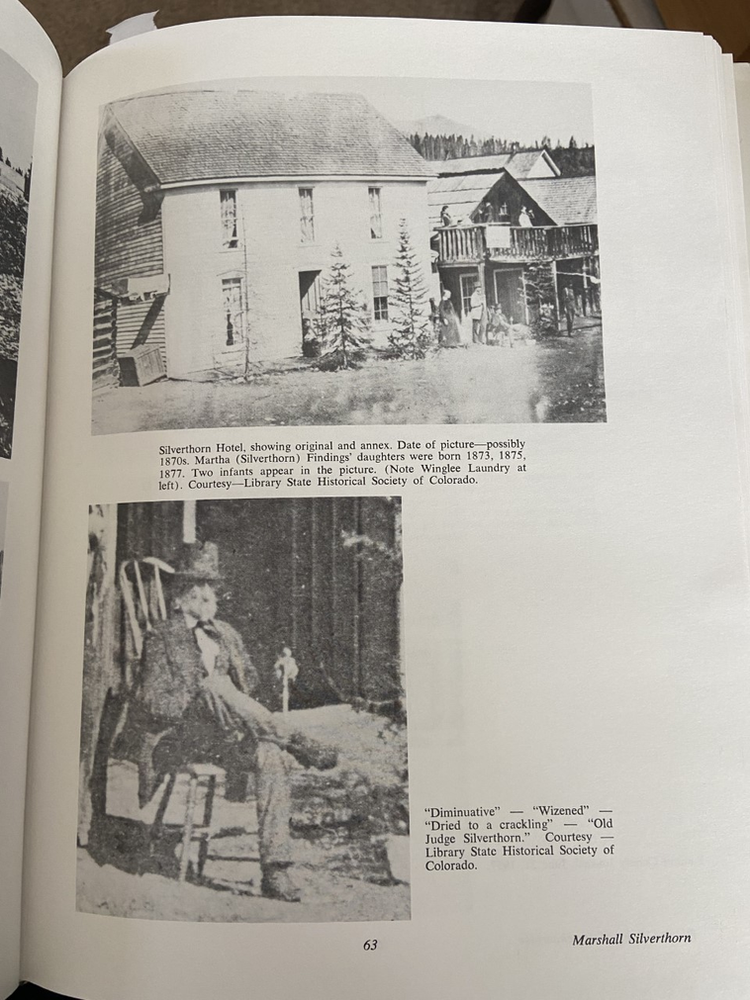

The Silverthorn family moved to Breckenridge in spring 1861 and set up a hotel. Like a momma bear, Mrs. Silverthorn fiercely loved and protected her family, both immediate and extended.

She was so beloved by the miners of Breckenridge, they sledded her down from Boreas Pass each spring upon her return to town (after retreating to lower elevations in the spring), yelling “hooray” on the way. Described as a “broad, buxom Matron,” she played the role of mother to the community, tending to the sick, feeding the miners, and caring for her guests. Saturdays were spent baking, using the entirety of a 100-pound sack of flour to make pies, bread, and cakes for the miners. Saturday was mail day and men streamed from their workings to the Silverthorn’s hotel for a taste of home.

Mrs. Silverthorn ensured that civilization was present in early Breckenridge. On Sundays, the hotel became a place of worship, with sermons read and hymns sung. Each winter she returned to Denver so her daughters could go to school (their son drowned in the Blue River in 1863).

When the county clerk tried to remove county records to rival town Parkville, Mrs. Silverthorn hid the burlap sack and “saved the county seat for Breckenridge.”

For twenty years, the Silverthorn family kept the community together, serving as good Samaritans and offering charity for the rough gold town built on greed. When Mrs. Silverthorn died in 1883, so too did the family business. By then, her daughters, “black eyed beauties,” were married and on their own. Marshall Silverthorn passed four years later.

Agnes Ralston Silverthorn’s success in Breckenridge was due to her motherly nature, just the kind of nurturing that early Breckenridge needed to mature into a community.

For more information about Agnes Silverthorn and the family, see Mary Ellen Gilliland’s book Summit: A Gold Rush History and Mark Fiester’s Blasted, Beloved, Breckenridge.

Catherine Rhodes Sisler Nolan’s husband, twenty-four years her senior, first came to Breckenridge around 1859 and claimed one of the richest patches of placer gold in the area: the west end of French Gulch where ancient glaciers deposited a mountain’s worth of free gold in its moraine.

Returning to Pennsylvania a wealthy man, he married Catherine Rhodes in 1865 and immediately set out again for Breckenridge. She raised their children while he mined, until his death in 1883. As the now-owner of the enterprises, Catherine Sisler took over management of the mines, partnering with John Nolan, an employee of Mr. Sisler’s.

Closer in age and with mining in common, the pair married in 1885. Yet John Nolan didn’t last long. On his death bed, just three years later, savvy Catherine Nolan made sure he signed over his property to her. From then on, she was in charge. Raised on hard work and understanding the value of a dollar, Mrs. Nolan was praised in the local newspaper: “to the credit of her good, business methods, no placer mine in camp is more admirably managed.”

Catherine Nolan amassed quite a fortune, branching out from mining interests to retail, ranching and landholding in Summit and El Paso Counties. According to her obituary, “to know her was to respect her.” Catherine is buried in Breckenridge’s Valley Brook Cemetery.

Catherine Sisler Nolan’s story illustrates a common theme in the West: women who were afforded the ability to succeed on their own had the opportunity to do very well, and led the way for future businesswomen.

To learn more about Catherine Sisler Nolan, see Bill Fountain’s book: Chasing the Dream: The Search for Gold in French Gulch.

John D. Roby arrived in Colorado in the early days of the gold rush, setting up in Breckenridge driving teams of mules by 1864. In 1866, he opened his first store and began his ascent in the community ranks, later serving as postmaster, County Treasurer, board member of the telegraph company, and Free Mason, in addition to selling his merchandise and mining. By the time Minnie arrived in town in 1875, he was a successful businessman.

Minnie Remine came from a family of resilient women. Raised in the mining community of Central City, her father died when she was young, and her mother raised three daughters on her own. Seeking greater opportunity, Mrs. Remine moved to Breckenridge in 1875 to open a boarding house, meeting with great success. Hospitality ran in the family. Minnie would become known for her many parties.

Once she was Mrs. John D. Roby, Minnie thrived in her role as mother and housewife, enjoying a lifestyle of wealth and privilege in booming Breckenridge. Card playing was her passion and she initiated the Ladies Card Club, excelling in whist, euchre and high-five. Lavish gifts were bestowed upon the winners of the competitive games. The prizes given sound like a queen’s ransom: sterling silver spoons, lacquered fruit dish, candle sticks, a silver toothpick holder, jardinieres, and a silver and gold-lined cream spoon.

In addition to card parties, Mrs. Roby threw elegant balls, and parties for birthdays, weddings, and graduations, where her skills as a “culinary artist” would shine.

Mrs. Roby found time to serve as an election judge, school board member, and librarian, sold war bonds and raised money for the Red Cross, encouraged charity as a member of the Sisters Mustard Seeds, supported her church, and was active in both the Women of Woodcraft and Eastern Star. Her published histories of Breckenridge provide considerable information for historians. She also gave birth to ten children, six of whom survived.

Breckenridge was a lively and fun place thanks to the generosity and hospitality of women like Minnie Remine Roby.

In contrast, sad Anna Sadler Hamilton chafed nearly every minute of her time in Breckenridge. Arriving in 1885 as the young bride of Robert Hamilton, a popular and cheerful meat market owner, Anna’s diary is filled with lament. Perhaps opposites do attract, as Anna was neither popular nor cheerful. Newspaper accounts of the domestic dealings of Robert omit any mention of Anna. Though she tried to make friends, she confided to her diary that one woman in town made her “sick,” another had “a tongue that runs like a sawmill” and her daughter was “silly and insipid,” and yet another woman was “horrid.” The men were no better. To one group loafing on a corner, she wanted to “make a face at them.”

Self-isolating in her petulance, Anna Hamilton spent time worrying about family back home, wondering why they didn’t write. She hated housekeeping, sewing and cooking, all jobs expected of her in her role as wife. She loathed snow and wind. By 1887, she mustered the courage to tell Rob that she didn’t want to live in Breckenridge any longer. Further pushing away her husband, he turned to drink. Anna felt neglected and she was. Her birthdays weren’t celebrated and Rob gave her no Christmas gifts in 1887.

In fall of 1887, Rob sold the meat market and engaged in the sawmill business. Not long after, Anna got her way. The family moved to Nebraska where Rob finally found significant financial success as a stockman.

Yet Rob Hamilton was not done with Breckenridge. He returned in 1909 to visit, bringing Anna and the children with him. By 1911, the family was back in Denver and Rob invested in a 700-acre ranch on the Lower Blue River north of Breckenridge. He continued to own mining interests in the area.

The end of life of Anna Hamilton is not known. Jen Baldwin, genealogist and family historian in Colorado tried to research Anna’s life and came up empty. All we have of her sad life is recorded in her diary. Baldwin believes that Anna died sometime around 1914.

Not all women who came to Breckenridge contributed to the community in lasting ways. A lot of women were like Anna Sadler Hamilton, misplaced and miserable in the high mountain mining camp. Were it not for her diary, she would have disappeared entirely from Breckenridge history.

To learn more about Anna Sadler Hamilton and the women of the frontier, see Sandra Mather’s book: They Weren’t All Prostitutes and Gamblers.

History recognizes the influencers, the people who made the community and gave of their unique talents to create a durable Breckenridge. As we celebrate Women’s History Month, we seek to remember the influencers, capture diverse female voices, and share the stories of the stalwarts, the Agnes Silverthorns, Minnie Robys and Catherine Sislers, women as tall as our mountains. To learn more about Breckenridge’s history, visit a museum, take a tour, or read our blog articles.

Written by Leigh Girvin