Saloons in Breckenridge

April 08, 2022 | Category: Breckenridge History

Probably no business establishment on the mining frontier played a more important role than the saloon. Whiskey, the primary refreshment sold in the saloons, arrived in what became Summit County during the reign of the mountain men (1820-1850). Each autumn, trappers and traders gathered at predesignated rendezvous spots, such as LaBonte’s Hole at the confluence of the Blue River, Snake River and Ten Mile Creek, to exchange their pelts for items needed for the coming winter such as gun powder, lead for bullets, rifles, knives, coffee, sugar, blankets and tobacco. A large part of what the traders brought was whiskey and lots of it.

Probably no business establishment on the mining frontier played a more important role than the saloon. Whiskey, the primary refreshment sold in the saloons, arrived in what became Summit County during the reign of the mountain men (1820-1850). Each autumn, trappers and traders gathered at predesignated rendezvous spots, such as LaBonte’s Hole at the confluence of the Blue River, Snake River and Ten Mile Creek, to exchange their pelts for items needed for the coming winter such as gun powder, lead for bullets, rifles, knives, coffee, sugar, blankets and tobacco. A large part of what the traders brought was whiskey and lots of it.

The first recorded gold strike on the Blue River occurred August 10, 1859. Just six months later, the Rocky Mountain News noted that wagons and tents, as well as “stores, dwellings, shops, and saloons,” lined the Blue River. Bayard Taylor, in 1866, told of enjoying a hearty meal complete with a barrel of beer on tap in Breckenridge.

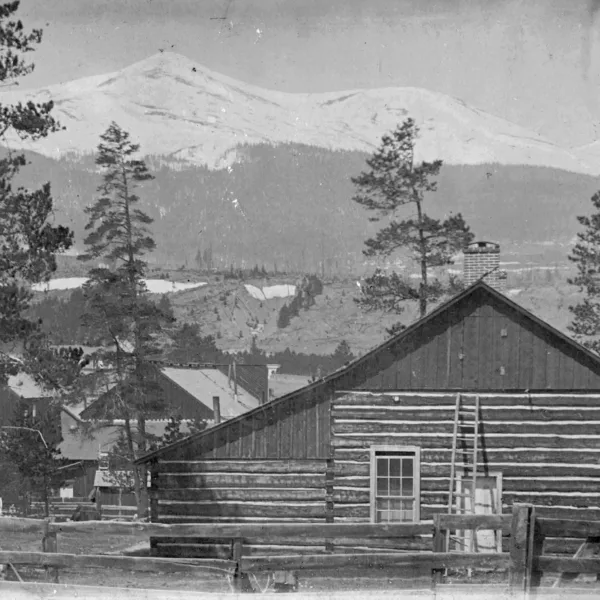

The very first saloons might have been wagons with “saloon” or “whiskey” written on them. Empty kegs with a board on top might have been the first “bar.” Some saloons operated out of tents, a step above dispensing whiskey from wagons. Perhaps the structure had wooden sides with a canvas roof on top. Ornate, hand-carved bars appeared first in saloons located in log and wooden frame buildings, sometimes with a false front that provided space to advertise the business. From these humble beginnings, the saloon rapidly became an ornate establishment complete with diamond dust mirror and real whiskey.

Why so many saloons? Primarily, saloons bolstered the male ego. They emphasized all the masculine traits of the mainly male population. They also filled a need. In them, men found comfort, a refuge from loneliness. Patrons preferred becoming part of the crowd at a saloon to spending an evening in a lonely log cabin. Saloons provided a place to eat, drink, sleep or simply relax. Men could gamble, dance, exchange news and gossip, discuss local and national topics, perhaps get a haircut, attend to civic duties, vote in elections, file claims, attend religious services, weddings, or funerals, or receive rudimentary medical attention from visiting doctors or dentists. In some establishments, men could find female companionship.

Saloons often functioned as the first courtrooms with the barkeeper serving as a judge. Common sense prevailed. All of this changed with the involvement of ever-present lawyers in the proceedings. Elections for town officers might be held in a saloon. Since courthouses were one of the first civic buildings constructed in a town, saloons filled this need for only a short time. Some saloons provided mail boxes to rent, while others posted employment and other notices. Before hospitals, those suffering from medical emergencies might be brought to a saloon for treatment. Whiskey served as an anesthetic. Because men showed reluctance to leave the gambling tables, ministers took their message to them–in the saloons. After the service, the men passed the hat to get “a little something for the preacher.” Father Dyer lamented that men preferred to go to the bar to drink and play cards–even on the Sabbath. Some saloons, such as the Engle Brothers saloon on the northeast corner of Lincoln Avenue and Ridge Street, provided a fireproof safe for its patrons to use. When it came to honesty, many preferred saloonkeepers to bankers.

Some saloons doubled as hotels, although accommodations and food could be rather poor. When “real” hotels opened, the hotel/saloon became a saloon only.

Although the centrality and importance of saloons diminished as courthouses, doctor’s offices, banks, churches, lodges, a post office, hotels and restaurants opened, towns bragged about the number of saloons serving their residents. A large number indicated the prosperity of the town. In 1880, Minnie Roby, wife of merchant, John Roby, counted 18 saloons. She listed some of them: Weinberger and Brothers, liquors and cigars; Norris and Thornton Club Rooms; the Mammoth Circus Tent Club Rooms, Hodges and Staff; A. Cline and Company, wholesale liquor dealers. Hotels also sold liquors: Fisk’s Hotel, Carbonate House, the National Hotel, the Arlington Hotel, the Denver Hotel and the Grand Central Hotel.

To attract customers, saloonkeepers decorated their walls with artwork. While drinking, the men might gaze at a portrait of a nude woman, with the shape of a base violin, hanging above the bar. Or it might be posters advertising a specific brand of beer or a boxing champion. Or the heads of animals taken during a hunt. Or witty signs: drink and leave quietly.

Advertisements filled the newspapers:

- “For a schooner of grand beer go to Hammerschlag’s to-night.

- To-night and to-morrow there will be a good time at Hammerschlag’s Denver saloon on South Main street. George keeps the best beer to be had and everything connected with his place is first class.

- Billiards, oh yes! If you want an hours amusement in that line drop in at the Grand Central saloon, you can find food tables, a quiet place, a gentleman partner, good cigars and choice liquors.

- Beer! Beer! Beer!

- Table wines, I also have a fine line of celebrated Kelly Island Catawba wines for sale now to the trade; or in quantity for table use–at the bar of the Palace Saloon.

- Fancy Cocktail and other Mixed Drinks Equal to The Best in the Land”

Saloons often catered to particular cultural groups. The Palace Saloon hosted the Teutonia Leiderkranz, a German singing society.

The success of a saloon rested on the shoulders of the barkeeper. P.S. Daigle, the bartender at the Denver Hotel enjoyed a fine reputation for keeping the “neatest and best bar in the city.” He had “the best Kentucky Whiskey and his cigars cannot be beat. Daigle is one of the few men who know just how to run a bar.” Residents held the barkeepers in high regard and included them in the same social group as doctors, bankers, and newspaper editors. A barkeeper’s clothing evolved through the years, from the rough and ready attire of the 1860s and 1870s to clean white shirts, vests, and jewelry.

Saloonkeepers used many “tricks” to draw customers and to increase the number of drinks poured. The first drink after a miner’s long shift might be free; sometimes the first drink of the day came free. Of course, some made the rounds of several saloons, getting that “first” free drink. Bartenders encouraged “treating.” Not only did it enhance camaraderie, it greatly increased sales.

Saloons had an assayer’s scale to measure gold dust, the medium of exchange. “How much can you raise in a pinch?” came from the mining frontier. A pinch of gold dust between thumb and first finger equaled twenty-five cents. Many other expressions still in use today came from the mining era. One such expression is “to bite the dust.” Sawdust covered the floors of many saloons, which made cleaning easier. The sawdust could be panned for any gold that fell from pockets or fingers. When a person imbibed too freely and fell to the floor, he “bit the (saw)dust.”

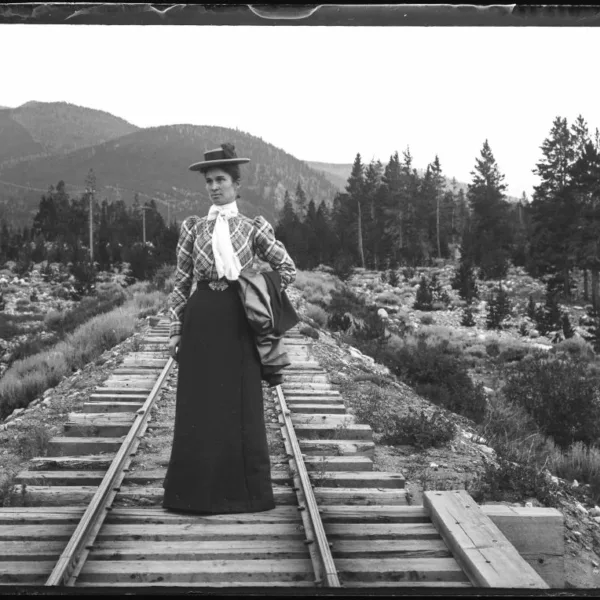

Saloons began offering food–free lunches in some; holiday feasts in others. With the coming of the railroad in the early 1880s, saloonkeepers could offer fresh fruits, vegetables and meats transported by refrigerated cars.

The Gold Rooms on Main Street showed the complete transition to an establishment catering to businessmen. One room had elegant gold wallpaper with “all the surroundings to match.” The newspaper advertised another room intended for the “private use of gentlemen patrons, furnished with writing materials, stationery, etc.”

Weaver Brothers Corner Saloon at the intersection of Main Street and Lincoln Avenue noted that its drinks were “seductive but seldom intoxicating.”

Over time, the atmosphere in mining towns such Breckenridge changed. The rugged individualism of independent prospectors and placer (plă’ ser) miners disappeared. Large companies bought out individuals; it was better economically to consolidate claims. Now the miners worked for others–seven days a week, ten-hour shifts–rather than for themselves. The saloon no longer functioned as the domain of the hearty miner hoping for a lucky strike. Rip-roaring days receded into memory. Lodges, fraternal organizations, political parties, literary societies and reading rooms drew customers from the saloons, replacing drinking and gambling with more sedate activities. More and more, customers included company men discussing world economics, mining practices, new machinery and labor problems.

Large companies enjoyed the advantage of investor funding–although the investing might not have been done wisely. Residents and merchants preferred this new respectability that would lead to prosperity–everyone’s ultimate goal.

written by Sandra F. Mather, PhD