April 08, 2022

An Overview History of Breckenridge

Breckenridge History is the leading authority on the rich and colorful history of our town. We are a small non-profit with a dedicated and passionate team of staff, volunteers, and historians. Part of our mission is to share our town’s heritage with the public and we offer museums, tours, hikes, and gold panning here in charming Breckenridge. For those who prefer a good read or can’t make it to Breckenridge to visit us, we’ve written essays on various topics.

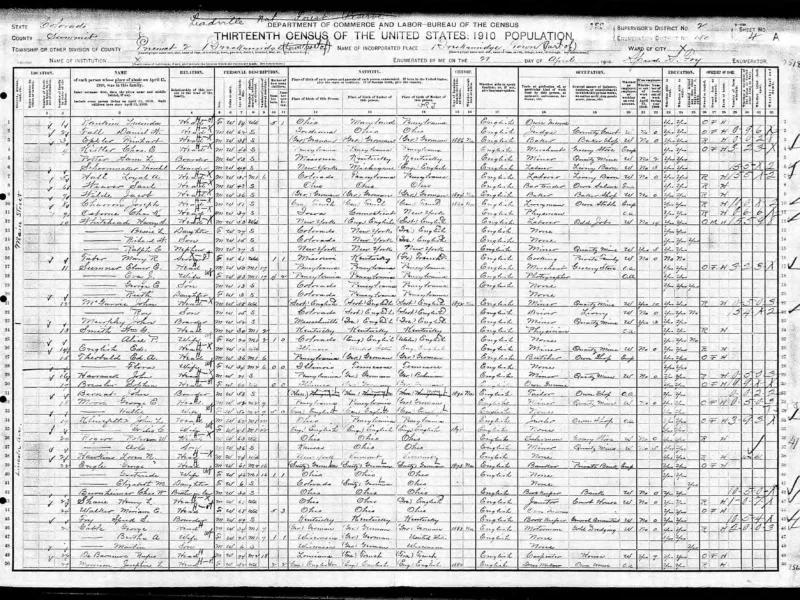

The Women of Breckenridge

Who were the women who came to Breckenridge in the 1880s? Where did they come from? Did they willingly make the trek to Breckenridge? What did they find when they arrived? Census data and diaries tell the story.

The Naming of Breckenridge

How did Breckenridge get its name? Historians have debated this for decades. Researchers have studied documents looking for the truth. Two stories emerge–both have elements of truth. Some think that John Cabell Breckinridge, who served as vice-president under James Buchanan before retiring to the U.S. Senate representing Kentucky after his term as vice-president ended, is the namesake. Others say the name came from Thomas E. Breckenridge, a member of the 1845 and 1848 Fremont expeditions. Bill Fountain studied the documents and put the pieces of the puzzle together.

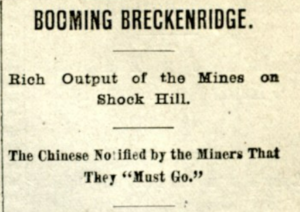

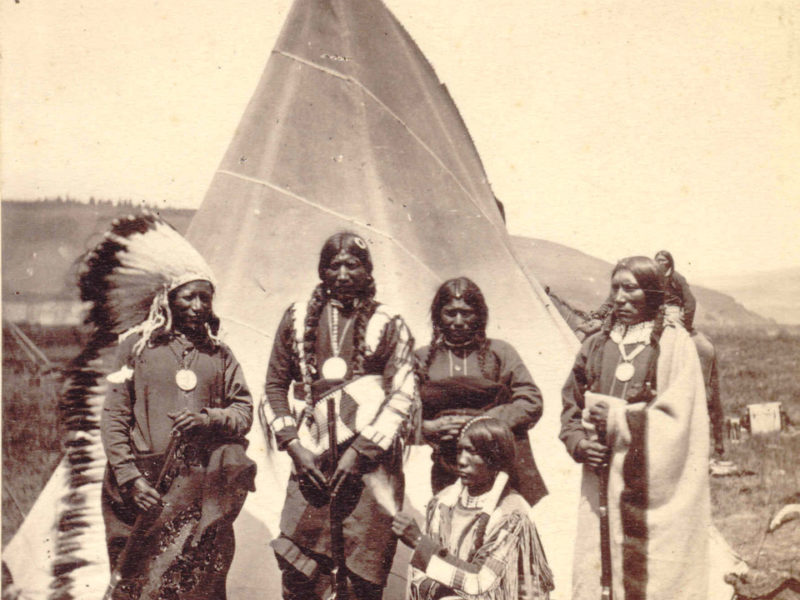

The Mountain Utes

For thousands of years, the nomadic Northern Utes and their ancestors traveled through what is today’s Breckenridge in search of food. They followed bison between summer grazing land on the Blue River and winter quarters at lower elevation (Lower Blue). The passes used by Utes became early wagon roads and present day highway routes. The Utes burned the valley floor each year to encourage the growth of grasses that bison preferred. This tradition changed the vegetative landscape, encouraging the growth of species like the lodgepole pine, whose cones open up after being exposed to heat.

The Assay Process

How did the individual prospector roaming the hillsides with his burro, pan, and pick know if he had found economically valuable ore? How did a mining company know if the ore produced could earn a profit for the company? They both depended on chemical assays. Every prospector knew how to do a “field assay” to determine the worth of his ore. Mining companies employed an assayer working in a well-equipped assay office to complete the task.

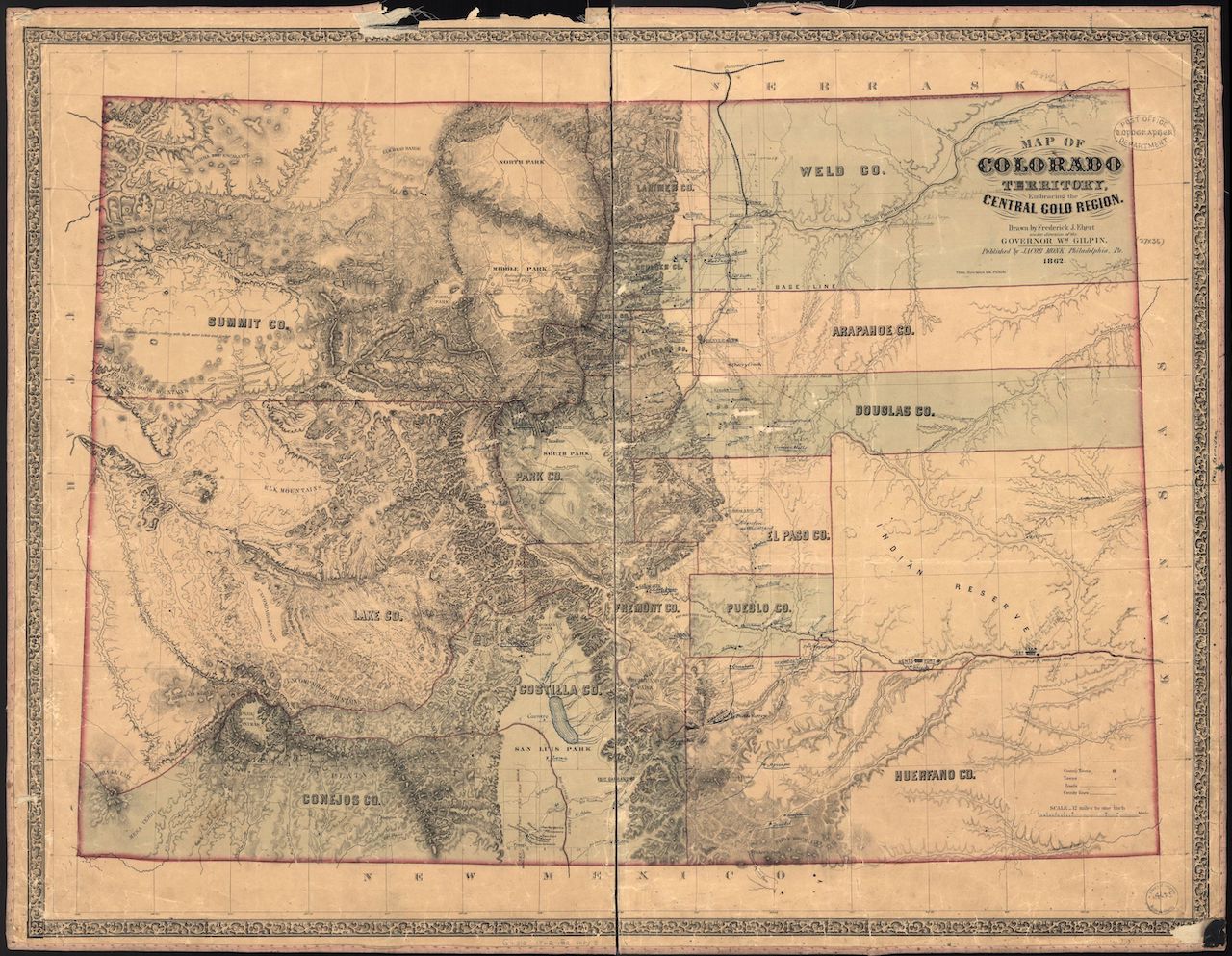

Summit County Boundaries

Prior to the creation of Colorado Territory, the land that became Colorado was divided among the territories of Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico and Utah. Land west of the Continental Divide, including what became Summit County, belonged to Utah Territory. Colorado’s First Legislative Assembly approved legislation entitled ”An act to define county boundaries and to locate county seats in Colorado Territory,” on November 1, 1861. The act established the boundaries of Summit County as the Continental Divide on the east, Lake County on the south and, on the north and west, the territorial boundaries.

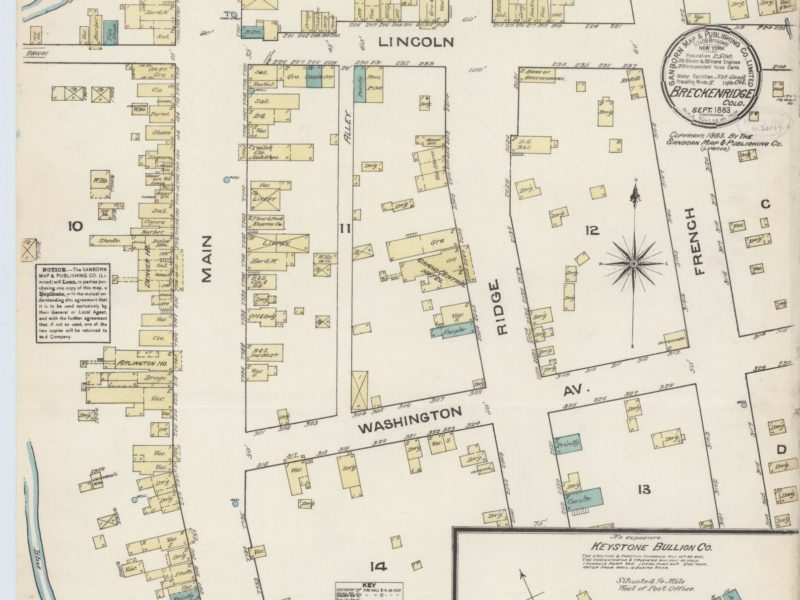

Street Layout of Breckenridge

Not long after prospectors found gold in what is now Summit County, mining camps blossomed along the waterways and gulches. Similar in appearance, they showed little planning or organization. Selecting a spot near wood and water, they placed their tents and crude log cabins haphazardly on or near claims. Only later, when claims had to be surveyed, did any semblance of order or organization develop. A main street, nothing more than a pathway through stumps and boulders lined with tents and rectangular buildings sporting false fronts advertising food, clothing, drink or supplies, appeared.

Saloons in Breckenridge

Probably no business establishment on the mining frontier played a more important role than the saloon. Whiskey, the primary refreshment sold in the saloons, arrived in what became Summit County during the reign of the mountain men (1820-1850). …

Recreation in Early Breckenridge

Men, women, and children in Breckenridge faced lives of hard work and danger. Long hours laboring in mines or hauling freight over muddy, rutty roads–cooking, cleaning, sewing, or managing boarding houses–helping fathers on a farm or in a store or mothers with housework–all left little time for recreation but “recreate” they did–summer and winter, indoors and out, individually or with others. Skiing, ice skating, hunting, cycling, fishing, card games, dancing, singing in choral groups, participating in club activities, hosting dinner parties and other social events–all provided respite from daily life.

Population of Summit County

The population of Summit County and its towns rose and fell with the fortunes of mining.

From an initial estimate of “hundreds” in the county in 1860 during the first gold rush, the number dropped to 258 by 1870. With the second boom in 1880, the number of residents grew to 5459, only to drop to 1906 by 1890 because of the looming national silver crisis.

Placer Mining

If it weren’t for the glaciers that filled the alpine valleys as recently as 10,000 years ago, the history of Summit County would have been quite different. Glaciers and running water (rain and snowmelt) eroded gold-bearing rocks in the mountains and carried the flakes of gold into the county’s streams and rivers. There they settled to the bottom of the deep glacial gravels that filled these valleys to depths as much as 90 feet.

Governance in Early Breckenridge

When the first prospectors and miners arrived in what would become Summit County, no legal or governmental structure existed–no federal, state, county or town governments, no sets of laws–to guide their interactions. This lack of a structure presented problems. How did one file a claim? How did one keep others from stealing that claim? How could disagreements be settled? To alleviate the problem, miners and prospectors adopted an idea used in California–the mining district.

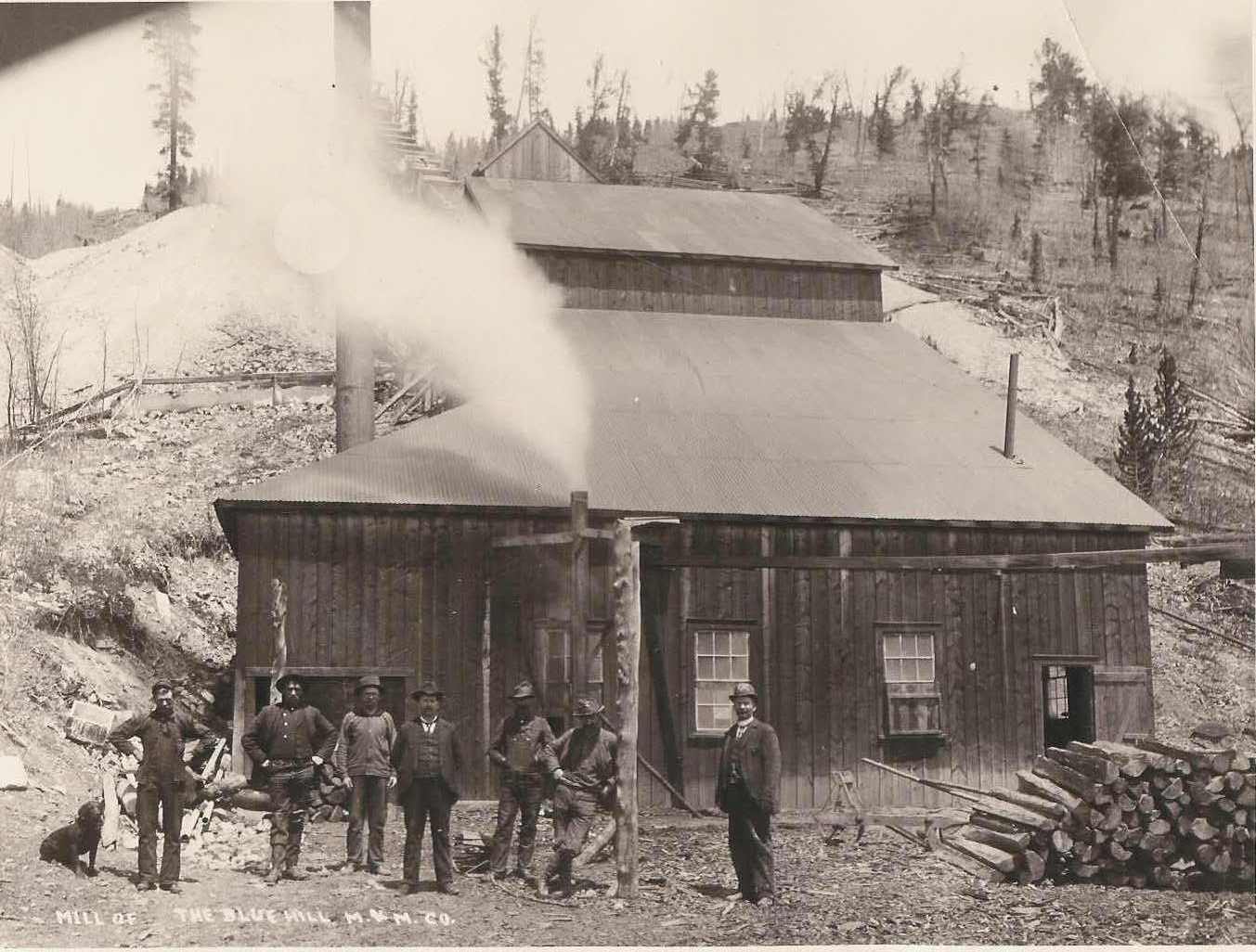

Gold Milling and Concentration

Nuggets taken from streams and free gold retrieved by panning, sluicing and dredging could go directly to the smelter. Before the gold found in the ore taken from hard rock mines became gold ingots or gold coins, it went several complicated rounds of chemical and mechanical processing. Men and machines at mills worked together to pulverize and break down the ore, discard the waste rock and prepare the concentrated ore for further processing.

Fraternal Organizations in Breckenridge

Fraternal and benevolent organizations thrived in the late 1800s. With at least several hundred in existence, they filled a need during a time of great societal change. Westward migration, the influx of European immigrants and improved transportation all created a more fluid society that still searched for and socialized with those of similar values, political learnings and religious and ethnic backgrounds. The largest fraternal organizations at that time all had chapters in Summit County: the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, the Improved Order of Red Men and the Knights of Pythias.

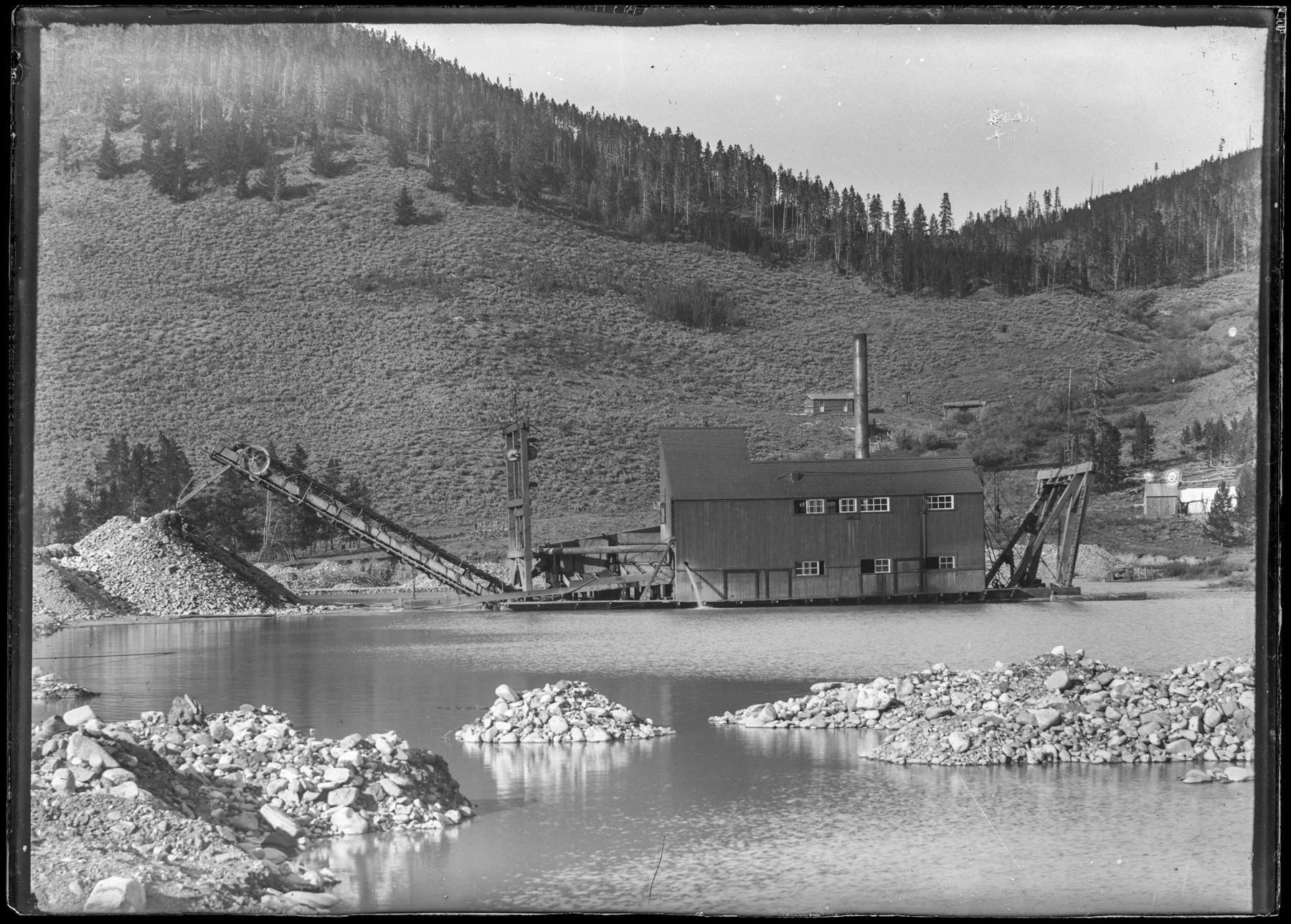

Dredge Boat Mining in Breckenridge

Breckenridge and southern Summit County experienced three mining booms. The first, lasting from 1859 until the mid-1860s, brought prospectors who looked for the “easy” gold–the nuggets in streams, the pieces laying on the ground and buried in shallow soils on the hillsides. They used pans, rocker boxes, long toms, and later high pressure hoses called “giants” to wash the gold-filled soil into sluice boxes. The second boom, the hard rock mining boom, began in the 1870s. Rather than the individual prospector chasing his dream, companies hired miners and others to work the mines.

March 24, 2022

Denver, South Park & Pacific Railroad

The mining and agricultural economies of Summit County required cheap, efficient transportation. From the spring of 1859, when prospectors first found gold, adequate and reliable transportation meant the difference between economic advantage and stagnation. Without it, ore, hay, timber, sheep and cattle could not reach local or distant markets; food, clothing and mining and agricultural equipment and supplies would not be available for those who needed them.

Breckenridge and Boreas Pass

For centuries, numerous passes over the Continental Divide allowed people to enter or leave what is now Summit County: Ute Pass in the Williams Fork Range, Loveland Pass, Argentine Pass -formerly known as Sanderson’s Pass and Snake River Pass, Grizzley Pass, Webster Pass – formerly known as Hand Cart Pass, Georgia Pass – formerly called Swan River Pass, French Pass, Hoosier Pass – formerly called Ute Pass, Fremont Pass, Shrine Pass, Vail Pass—–and Breckenridge Pass. Breckenridge Pass? Where was Breckenridge Pass? Was it originally Hamilton Pass as some have said? Or is it a separate pass with an unknown location? Could it be the original name of Boreas Pass?

March 14, 2022

A Day in the Life of a Miner

The day started early and ended late for miners and others working in the mines of Summit County. Mining companies expected their workers to be down in the mine at 7:00 a.m. ready to go. This required the miners to rise early and walk or ride to work, sometimes in heavy snow and the darkness of the winter months, from a family home, boarding house or perhaps company housing.