The Assay Process

April 08, 2022 | Category: Breckenridge History

How did the individual prospector roaming the hillsides with his burro, pan, and pick know if he had found economically valuable ore? How did a mining company know if the ore produced could earn a profit for the company? They both depended on chemical assays. Every prospector knew how to do a “field assay” to determine the worth of his ore. Mining companies employed an assayer working in a well-equipped assay office to complete the task.

How did the individual prospector roaming the hillsides with his burro, pan, and pick know if he had found economically valuable ore? How did a mining company know if the ore produced could earn a profit for the company? They both depended on chemical assays. Every prospector knew how to do a “field assay” to determine the worth of his ore. Mining companies employed an assayer working in a well-equipped assay office to complete the task.

The field assay could be dangerous. The prospector washed the materials in his pan down to the finest gravels and (he hoped) flakes of gold. He added liquid mercury already impregnated with gold to his pan. Mercury can absorb as much as 50 percent of its weight in gold. When the mercury became solid and crusty, he knew it could absorb no more gold. He put the amalgam of mercury and gold on a shovel and held it over a fire, evaporating the mercury. Of course, he had to be sure not to breathe the deadly mercury fumes. Some prospectors knew a way to prevent the mercury from escaping into the air. They placed the amalgam in a hollowed-out baking potato, wired the halves together and tossed the potato into the fire. The potato absorbed the evaporating mercury, leaving the gold. We can only hope that the prospector knew not to eat the potato no matter how hungry he might be.

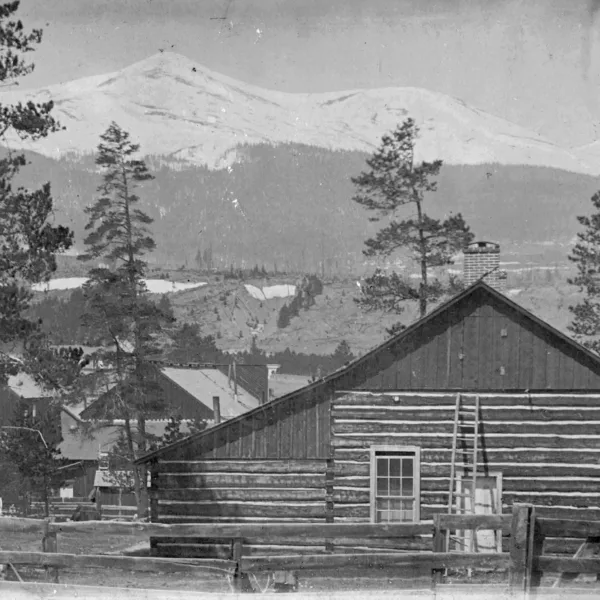

All of the large mine complexes had a well-equipped assay office. Independent assayers in towns might serve small mining operations or individuals. Each assay office generally had three parts: a front office with desk, cupboards and shelves for reference books, specimens and supplies; a laboratory with furnace, work tables, glassware, crucibles, cupels (kuh pells’) and other equipment such as funnels, filters, pokers, scrapers and tongs; and a back room with crushing and screening apparatus, brass molds to make the cupels, and lots of rock dust. A dust-free area housed delicate scales and balances.

Highly respected and well-trained assayers with an extensive background in chemistry and chemical processes staffed the offices at the mines and in towns. The assayers followed a very precise and complicated process in determining the worth of the ore.

Assayers often hired a strong, young apprentice to complete the first step of the process: using a variety of heavy equipment to crush the ore to sand size. The assayer then divided the crushed ore into samples weighing exactly 29.167 grams, called an “assay ton.” Since there are 29,167 ounces in one ton, the amount of gold left in an assay ton would be used to judge the amount of gold in a ton of the ore from which the sample had been taken.

The assayer mixed one sample in a crucible with chemical reagents such as litharge (lead oxide), borax (used in place of salt), powdered argol (a salt from which cream of tartar is made), wheat flour, charcoal, saltpeter and silver. Reagents served as fluxes, combining with other chemicals to draw them out of the mixture; as solvents, dissolving certain minerals; as reducing agents, subtracting oxygen from some chemicals; and as oxidizing agents, adding oxygen to other chemicals. Some served two functions. The assayer knew exactly how much of each reagent to add.

The assayer placed the crucible on the lower deck of a furnace fueled by gas or either coke, coal or charcoal. Here, carbon monoxide, helped by the wheat flour, drew off the oxygen from the lead oxide. With the furnace door closed, temperatures reached over 2,700 degrees F. After about 30 minutes, liquefied drops of metallic lead descended through the mixture, collecting gold and other metals. The assayer poured the “melt” into conical molds and allowed it to cool and solidify. With the knock of a hammer, he removed the cone from the mold.

Most of the cone contained worthless slag but the tip contained the valuable minerals. The assayer hammered the tip into a cube and placed it in a cupel, made of horse or sheep bone mixed with wood ash and potassium carbonate for strength, on the upper or oxidizing deck of the furnace. With a closed furnace door, temperatures in this step reached only 1,652 degrees F. (not hot enough to melt gold or silver). As the cube changed to a button shape, the assayer opened the door to add oxygen, needed to complete the process. The oxygen vaporized the lead; the cupel absorbed any lead not vaporized. When all of the lead had been released the button solidified and producing a flash of light. If the assayer wanted to watch, he looked through a board with a tiny slit in it.

Next the assayer washed, cleaned and weighed the button, now called a doré (doe ray’) bead. A bath for ten minutes in boiling nitric acid removed any silver remaining in the bead. After giving the gold a final bath in hot distilled water, the assayer weighed the gold and recorded the weight on a certificate. The costs of mining required four to five ounces of gold per sample for the ore to be considered profitable. The assayer followed the same procedure with all but one of the samples, which he saved in case someone questioned his honesty.

Although details might vary, assayers used this general process throughout the American West.written by Sandra F. Mather, PhD