What Happened to John C Breckinridge

January 24, 2022 | Category: Our Collective History

Lending his name to the town’s post office chartered in February 1860, John Cabell Breckinridge linked himself with the Town of Breckenridge from the beginning. Like it or not. And the people of Breckenridge didn’t like it. When Breckinridge jumped to the Confederacy in 1861, the people changed the name of the town back to Breckenridge. Who was John C. Breckinridge? What did he have to do with Breckenridge? And what happened to him?

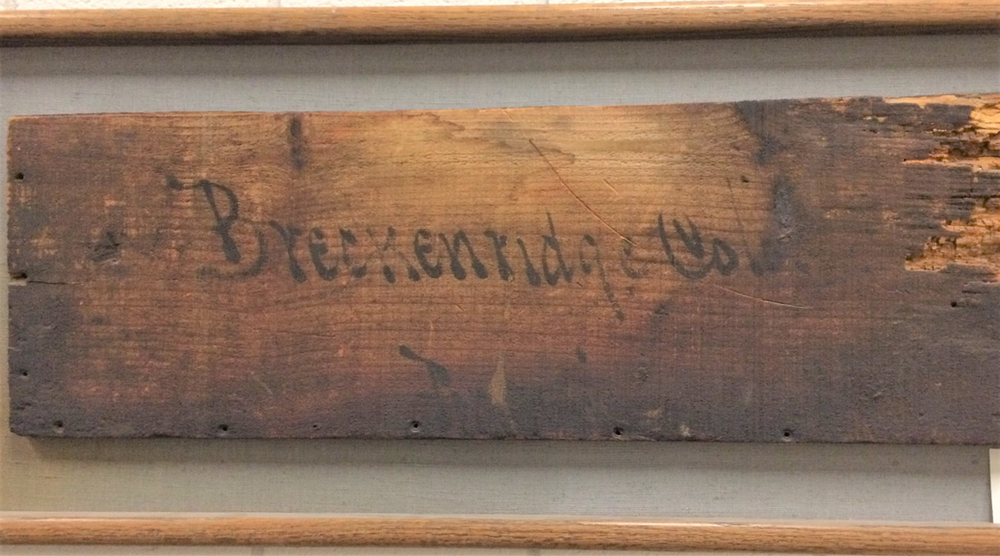

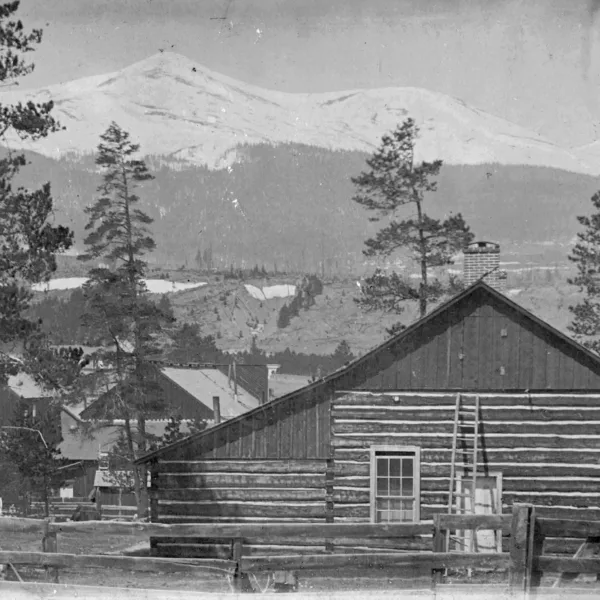

The 1859 gold rush to the Pikes Peak region brought hundreds of men to the Blue River Diggings and the Breckenridge area. Finding enough gold, men stuck around. A community developed. One of the ways to make money in mining was to plat a townsite and sell lots. George Spencer pursued the creation of the townsite. Knowing that his success depended on a post office, Spencer named it in honor of then-Vice President John Cabell Breckinridge. His ploy worked and the post office charter was granted by February 1860.

Breckinridge’s name has been associated with Breckenridge ever since. Learn more about naming lore and the murky history of the origins of the town of Breckenridge in this article.

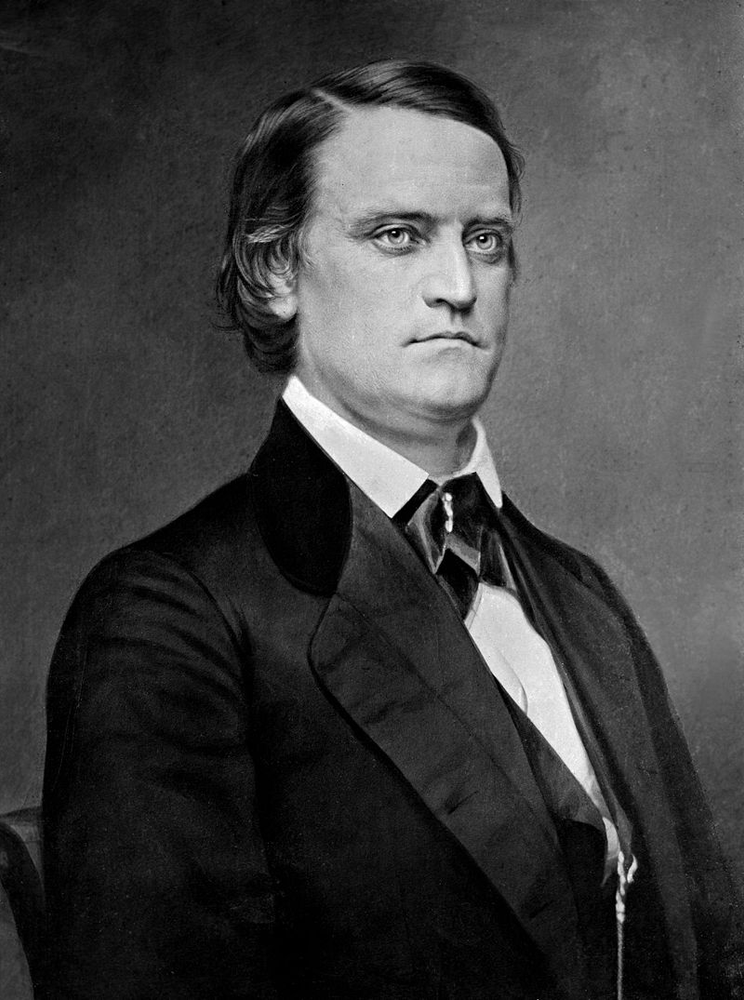

Who was John Cabell Breckinridge? Typical of the ruling class of Southern Democrats of the time, Breckinridge was born (1821) into a wealthy land-owning, slave-holding family that settled in Kentucky. One ancestor signed the Declaration of Independence. J.C. Breckinridge attended top schools and took up the profession of law.

Good looks, tall stature, strong oratory skills and a “reputation for dignity and integrity,” propelled Breckinridge’s political career. In 1849 he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives where he advocated for state’s rights against interference with slavery. Two years later the people of Kentucky elected him to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he allied with Steven Douglas, an Illinois Democratic Senator, who favored continuing the system of American Slavery.

Several years later, in the wake of 1857’s Dred Scott Decision, Breckenridge’s Barney Ford would align with other free black men to denounce Douglas’s assertion that the “negro is not, nor cannot be, a citizen of the United States.” Fords’ group argued in the Chicago Tribune that the Constitution of the United States recognized “but two classes in this country, citizens and aliens; we are not aliens, and therefore we must be citizens.”

Arguments for and against slavery would dog Breckinridge his entire career. His complicated relationship with the issue is seen in his family’s history. Two uncles were well-known abolitionists. Breckinridge himself was a member of two prominent abolitionist organizations, the Free Masons and Lexington’s First Presbyterian Church. Breckinridge also represented freed blacks in court and expressed support for voluntary emancipation. Political adversaries accused him of having a weak stance in support of slavery. Yet he personally enslaved five people of color, advocated for states’ rights to maintain slavery, and ultimately joined the Confederacy.

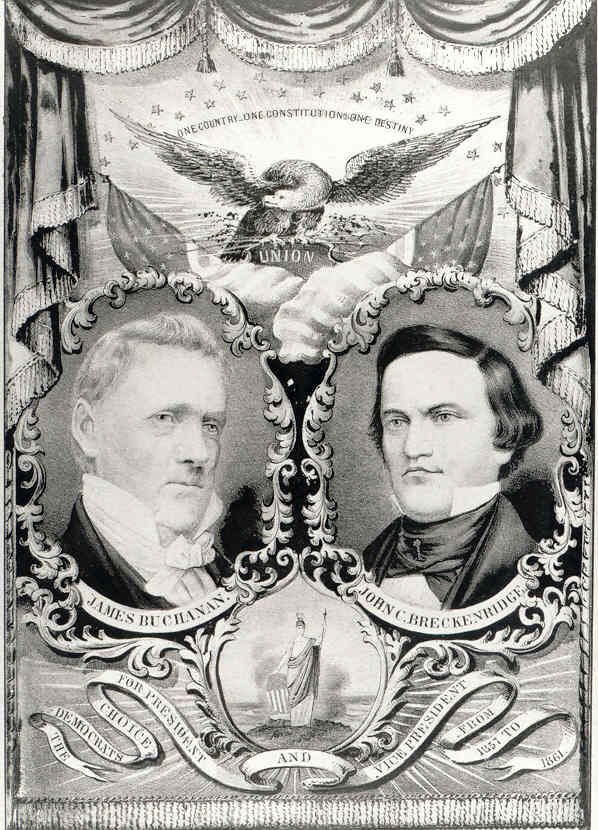

Breckinridge ascended the political ranks in the years following his service in the House and was elected to the Vice Presidency under James Buchanan, the youngest ever, taking office in 1857. He continued in that role until 1861 when Lincoln took over the White House. In the meanwhile, the people of Breckenridge/Breckinridge got their post office.

1860 was a tumultuous year in American politics. Breckinridge ran for the office of President of the United States, with the election scheduled for November. With three other supporters of slavery on the ballot, including Steven Douglas, the vote was split and anti-slavery candidate Abraham Lincoln won the presidency by taking most of the North’s electoral college votes. Breckinridge took a seat in the U.S. Senate after the election.

Not long after Lincoln was sworn into the Presidency in March 1861, Southerners increasingly agitated for secession. In autumn 1861, Breckinridge exchanged his seat in the Senate “for the musket of a soldier” and enlisted in the Confederate Army.

Around this time, the people of Breckenridge/Breckinridge began to call for a name change. The population was then a mix of northerners and southerners. It wasn’t so much that they were abolitionists; their concern was to keep slavery from the mining communities. They didn’t want rich southern slave-holders establishing mining empires on the backs of enslaved people, thereby crowding out the entrepreneurial spirit of the gold prospectors. Yet the name “Breckinridge” persisted in the official record for several years after 1861, gradually phasing out by the late-1860s.

John C. Breckinridge began his Confederate military career that November 1861, commissioned as a brigadier general for the 1st Kentucky Brigade. Solid performances gained him promotions where he oversaw troops in major battles of the Western Theatre in Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee and his own Kentucky. Later in the Civil War, his commission moved to the Eastern Theater where he distinguished himself in service to Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and played an important role in halting Grant’s advance at the Battle of Cold Harbor.

His reputation led to his appointment in February 1865 as Confederate Secretary of War. Breckinridge soon recognized that the Confederate cause was hopeless and he began to lay the groundwork for surrender. In April 1865, he oversaw the surrender of Richmond, Virginia. As he continued to retreat south, he learned of the death by assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14th, which left him visibly shaken. He believed that Lincoln was a friend to the South.

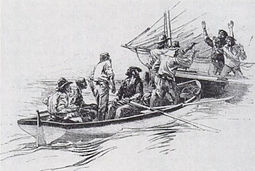

Traveling further south, Breckinridge was put in charge of the $150,000 in gold specie that remained in the Confederate treasury, yet most of it went to unpaid soldiers in his escort and other requisitions. Breckinridge escaped Federal troops by sea in May 1865 in a daring boat heist. Traveling down shore in a captured lifeboat, Breckinridge, with John Taylor Wood, a captain in the Confederate Navy, seized a sailing craft with mast and rigging, the No Name. Westerners will recognize this as the name of the boat that John Wesley Powell famously lost early in his 1869 exploration of the Colorado River and Grand Canyon. In that wreck, a third of his supplies and important equipment vanished. Historians believe that the Howland brothers, captains of the No Name in Powell’s expedition, dubbed their craft in recognition of the tiny sloop that Breckinridge used to escape.

Breckinridge fled to Cuba in a film-worthy adventure surviving an encounter with pirates, two significant storms, and near starvation due to lack of provisions. Now in exile, Breckinridge soon continued to Britain, then Canada where he reunited with his family. Perhaps he retained some of that Confederate gold as he spent 1866 through early-1868 touring Europe.

President Andrew Johnson proclaimed amnesty for all former Confederates on December 25, 1868. Breckinridge returned to Kentucky by March 1869 and embarked on a successful late-life career in the insurance and railroad industries.

In May 1873, Breckinridge died in Lexington, Kentucky, of cirrhosis of the liver, caused by so-called war wounds, though he was known as a heavy drinker and was accused at least once of drunkenness on duty. By this time, the people of Breckenridge, Colorado, had moved on. It was Breckenridge after all. And where did the name “Breckenridge” come from? That story is told in this article.

Several communities in the United States attribute their name to J.C. Breckinridge today: villages in Michigan and Oklahoma, towns in Missouri, Minnesota and Colorado, and the largest city, Breckenridge, Texas. Notably, all changed the spelling to Breckenridge over the years, with the exception of tiny Breckinridge, Oklahoma, which still hasn’t decided: searches reveal both spellings.

Confederates have lost favor in recent years. J.C. Breckinridge’s statue, formerly positioned on the courthouse lawn in Lexington, Kentucky, was moved in 2018 to his family’s Section G in the Lexington Cemetery.

To learn more about Breckenridge’s history, visit a museum, take a tour, or read our blog articles.

written by Leigh Girvin